Author’s Note: Insights shared here are taken from the CFO Mixer and Investor Panel held on February 2023 in Singapore hosted by Stripe, featuring a panel with Jason Edwards of January Capital and VentureCap Insights and Insignia Ventures’ Yinglan Tan, as well as a conversation with former Slack CFO Allen Shim.

Highlights

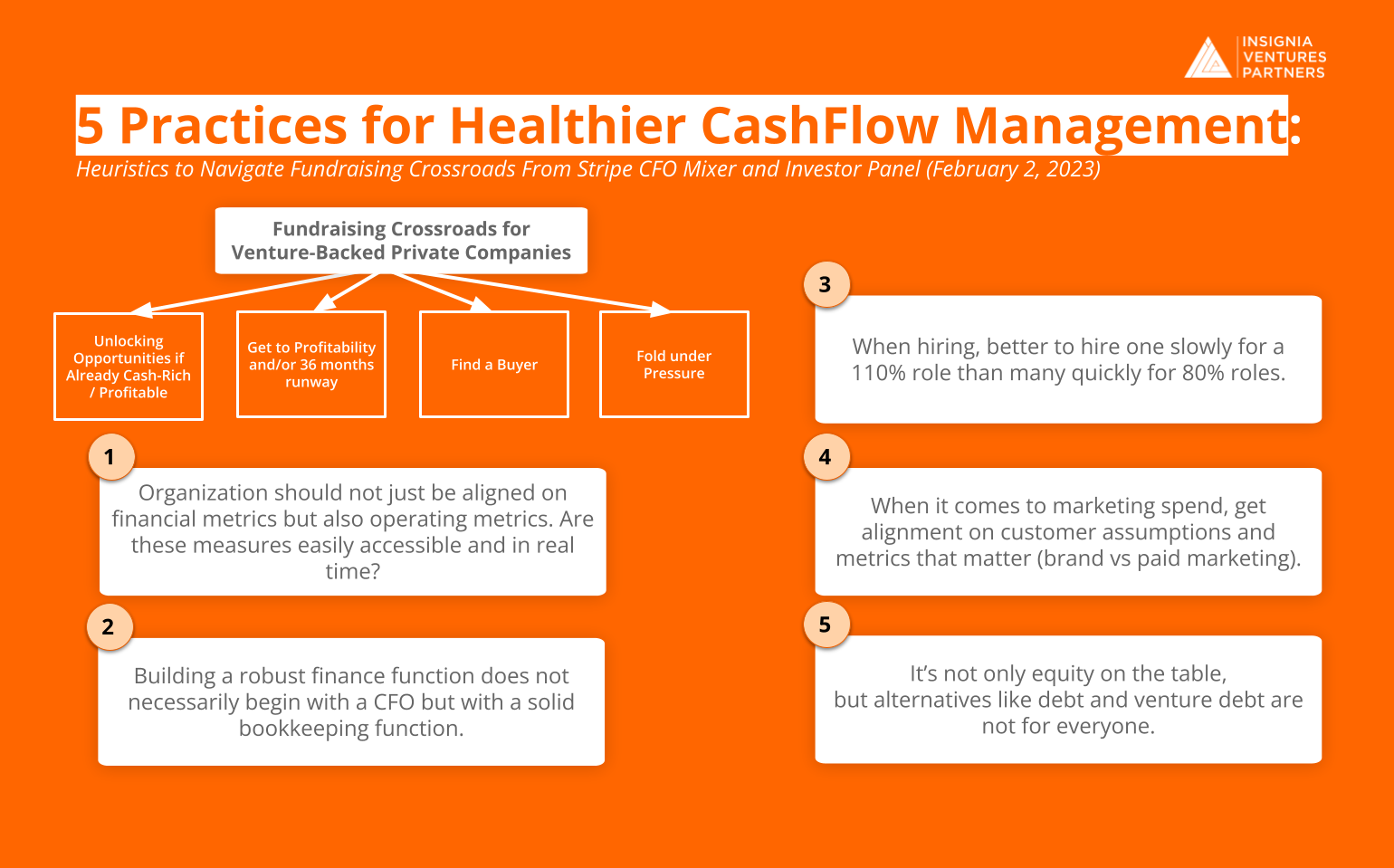

- Venture-backed private companies now face a crossroads in fundraising (i.e., To raise or to not? To take a valuation hit or not? To raise equity or debt or some combination?). This is compounded by the need to extend runways to survive in the case of some companies, or the pressure to capitalize on their competitive advantages in the case of others.

- From the investors’ perspective, especially late-stage investors where the correction’s impact is more severe, the bars are higher. The challenge is more pronounced for companies that raise at too high (or attractive) of a multiple and are now faced with potentially getting penalized for their last-round valuation.

- The crossroads companies face in this market could be illustrated in four or five possible scenarios: Already Cash-Rich, Get to Profitability or 36-month Runway, Take a Downround, Find a Buyer, or Fold under Pressure.

- 5 Practices for Healthier Cash Flow Management: (1) You can’t address what you can’t measure, (2) Robust finance function begins with solid bookkeeping, (3) Better to hire one slowly at 110% than many quickly at 80%, (4) When it comes to marketing spend, get alignment on what you’re actually measuring, (5) It’s not only equity on the table, but these alternatives (like debt, venture debt, and revenue-based financing) are not for everyone.

From fundraising heydays to fundraising correction: A Recap

“What we’ve seen leading up to the correction in the public markets was that there was an enormous amount of money coming into the startup ecosystem in Southeast Asia. And that was really caused by a number of factors,” shares Jason Edwards of January Capital.

These factors included many overseas investors investing massive amounts in the region for the first time, from the likes of Jeff Bezos to Sequoia pouring as much as 50M USD into first-time meetings. This flush of money in the year’s post “first-generation unicorn-minting” (the likes of Gojek, Traveloka, Grab) to the pandemic-induced digitalization rush (2018 to 2021) shifted the fundraising value chain in two ways. Late-stage investors were forced to move earlier because the prices went up in later rounds, while smaller funds that were able to raise much larger funds on top of the Southeast Asia potential sought to fuel larger fundraising rounds.

This capital influx closed the well-documented “growth-stage funding gap” in the region as money chased investments. Jason adds, “For founders, at that time, it was a heyday. You just had so much money chasing investments, and people were raising more than they needed. And the valuations were, I think, higher than they should have been.”

New market, new rules: higher bar for late-stage investors, higher standards for product-market fit, lower durability of cash

Now the script has flipped with the public markets correction, and venture-backed private companies now face a crossroads in fundraising (i.e., To raise or to not? To take a valuation hit or not? To raise equity or debt or some combination?). This is compounded by the need to extend runways to survive in the case of some companies, or the pressure to capitalize on their competitive advantages in the case of others.

From the investors’ perspective, especially late-stage investors where the correction’s impact is more severe, the bars are higher. In particular, Yinglan points out two key questions: “…when you talk to the late stage investors…they ask you two questions. One, are you profitable?…The second question they ask you is, do you have audited financials to fundraise?”

The standards for product-market fit have also changed, as Yinglan adds, “…the founders that have succeeded in the past five years could raise 10 million on a PowerPoint deck and could give subsidies to grow. They will not be the founders that will succeed in the next five years because the environment has totally changed, right? You have to show economics much earlier in the process. You have to have products that actually have product market fit. And when I say product market fit, it’s not just growth, transactions need to be EBITDA positive or really unit economics positive.”

The durability of cash has also changed. Before 12-18 months would have sufficed to ferry through another round and generate enough growth to make the markup justifiable, but now that may no longer be enough for most companies. It also takes much longer to raise money, given the more rigorous due diligence expected by investors. Given the higher bars for fundraising vis-a-vis price adjustments, Yinglan advises getting to 36 months or a three-year runway, if not profitability.

The challenge is more pronounced for companies that raise at too high (or attractive) of a multiple and are now faced with potentially getting penalized for their last-round valuation. As Jason puts it, “The challenge I think that really brings about is if you’re a good company that’s doing well at a late stage, and you’ve raised when the times were really good, you would’ve raised at a really attractive multiple. And that’s not gonna happen now. It’s all changed. So how do you avoid being penalized by what’s happening in the markets if you are performing well because you don’t want to have flat rounds and down rounds. So I think part of what you have to think about is managing that with the ability to raise…How do you make your runway work? That’s one thing people should think about.”

The Fundraising Crossroads: Already Cash-Rich, Get to Profitability or 36-month Runway, Take a Downround, Find a Buyer, or Fold under Pressure

With this in mind, the crossroads companies face in this market could be illustrated in four or five possible scenarios. First is that if the company is already cash-rich (profitable and/or has a three-year runway), then it’s time to be aggressive. If the company is not in that position yet, the obvious alternative is to make that happen.

So second is to focus on cutting burn to create a longer runway, or even better, refocus the business towards profitability. In some cases, the company is able to safely raise a bridge round or a decently priced follow-on to add to this cash “cushion” as they refocus the business. If the company has already done these measures but is still not in a safe position at the least, taking a down round may be necessary, or considering other instruments (venture debt, debt, and other revenue-based financing instruments) as we share later in the article.

If these measures still don’t work, it may be time to find a buyer to inject a significant amount of cash in exchange for ownership of the company. Depending on the founder or management, this may actually be the optimal choice, to ensure the product or service continues to be delivered and also relieve the pressure of having to navigate the bear market alone. That said, there needs to be buyer interest, to begin with.

Ultimately not all businesses will be caught within the safety of this crossroads, and others will fold under pressure, some more spectacularly than others.

While there are external factors to account for, how an entrepreneur can make it through this crossroads begins with a realistic and thoughtful response. As Yinglan puts it, “…what I see nowadays is that the more mature, thoughtful founders say it’s a great time. “We got fed last year. Now we are going to, more or less, see our productivity per employee. We made the hard decisions.”

5 Practices for Healthier Cash Flow Management

The crossroads just illustrated above is not a hard fast decision tree that applies to every company. This is just a simplified heuristic to illustrate the importance of building up healthy cash flows and runway if the company is to continue growing sustainably in this market.

With that mind, we list down five practices covered both in the panel previously mentioned and in a conversation with former Slack CFO Allen Shim that followed the panel. These practices go beyond fundraising and pure finance and apply to various aspects of company building, from internal communication to hiring and marketing. Note that these are practices (and not remedies) which means they are best applied as part of a company’s operating principles and management ethos, rather than as one-off actions.

Related read: Check out this article on practices for better governance with related items to consider apart from the five below

(1) You can’t address what you can’t measure. In that regard, it’s important for an organization to be aligned, not just on what operating metrics are important, but on how these metrics are tracked and can be communicated in real-time.

Allen shares from his experience at Slack how they approached creating robust data communication across their organization: “The main area that we felt a lot of pressure on more than finance in the classic way was data — operating metrics. This is a big topic in every company…Every company does this differently, but the thing that you really want and the thing that we found very, very important — so we used Slack and we integrated a bunch of bots that would shoot data into channels in an automated way — [is] making sure that that was always available to make decisions… there are different elements to what you’re asking, depending on what really matters…It’s going to be more what you’re comfortable with and more of the person that you trust to do that work.”

(2) Robust finance function begins with solid bookkeeping.

While what finance means to a company will evolve over time, so rather than getting caught up in whether to bring in a CFO as an early-stage startup (this is not to say one should avoid getting a CFO), having a solid bookkeeping foundation is an important first step — from tracking where is cash is going, the bank accounts being used, who is getting paid from where, who are the vendors, where are the expense reports, what accounting assumptions are being made, etc.

Allen shares that you might not need a CFO, to begin with, more than someone who can be in charge of financial management in the company: “The easy answer to any early stage shop is you don’t need a CFO in terms of what I think a CFO is. Maybe what you think a CFO is — do you need someone that is in charge of finance? On some level, yes, but what finance means for you will evolve in scope and grow over time…But I think with bookkeeping, you have got to feel very, very solid with that. Especially in the beginning. It doesn’t have to be super fast, but it just needs to be very organized in a way that you can always kind of find going forward…someone has to make sure that that foundation is solid. How are the books getting closed? Do you have competent bookkeepers? Are you making accounting assumptions without realizing it?”

(3) Better to hire one slowly at 110% than many quickly at 80%.

While the finer details of performance management and assessing capabilities at the hiring stage will vary from function to function and role to role, it is clear that companies that hired too many too quickly over the past few years are now having to reckon with the challenges of optimizing headcount and correcting pay for performance.

Yinglan emphasizes that founders need to think more carefully about the pay-performance fit in this market: “I think as a founder, [you need to] think what is the amount I want to pay for this role? Having the exceptions of course, in the process, but you really want to be careful at picking people nowadays.”

Allen attributes conflicting individual motivations from the management/leadership level as a key reason for companies to be tempted to “hire as a first resort”: “One of the things I noticed, especially when you’re growing very, very quickly is people think of hiring as a first resort. And there are a lot of conflicting motivations here, right? As individual managers, you’re like this is gonna be a big company…And so they all start building these massive, massive teams. So it’s very ego-driven. At the same time, [maybe] you think that it’s important because that’s what the company should be investing in because maybe you’re the sales leader and you say, I need more salespeople…So I’m not saying these are all necessarily bad motivations, but they are individual-based motivations…”

What these individual-based motivations have resulted in is organizations with too much filling in people in what Allen calls, “80% jobs”: “And so what that means is four days out of a five day work week, they have something that they do that fully occupies them…but that means that one day of the week they have nothing to do effectively, because it’s not well defined for them. There’s already a lot of overlap because now all of a sudden two teams are working on the same thing from different angles…And so when you can get a company that learns how to operate at 105, 110% of your existing capacity, then the next hire easily picks up a hundred percent job because they start to actually have a role that’s fully fit for them.”

(4) When it comes to marketing spend, get alignment on what you’re actually measuring.

Another big bucket of spending companies that often generates a lot of debate is marketing. At the end of the day, there needs to be alignment on the impact that needs to be generated, regardless of where the company’s approach lies on the spectrum of approaches (e.g., paid marketing in itself is not necessarily ineffective, nor is brand marketing always the way to go). Lack of alignment can lead to assumptions (on brand perception, on LTV) that no longer hold once the market conditions change.

Allen points out how unstable justifications can lead to paid marketing mishaps: “…basically what has happened is people bought their way to growth in a lot of ways, whether it’s through Facebook ads or other paid marketing engines. And they justified it by saying, “Look at all this great ROI I have. If I hit my 40, 50% ROI threshold, let’s keep putting money in.” And it’s a siren song, right? It’s really dangerous because if it doesn’t actually stand on its own merit, once the money’s gone, there’s nothing there, right? And then all of your LTVV assumptions start to go out the window because they’re actually not retaining at the same level. You can see how that becomes a ripple effect and you’re seeing that play out here…”

(5) It’s not only equity on the table, but these alternatives (like debt, venture debt, and revenue-based financing) are not for everyone.

Specifically, when it comes to venture debt, this instrument is still quite nascent in terms of adoption in the region (15% in the US, 2% in Southeast Asia for venture debt, according to Jason) given the lack of supply and demand overall. But when leveraged in the right scenarios, venture debt can be used to extend runways in the interim as the company focuses on adjusting its trajectory for a more realistic up-round. Also, it’s less dilutive than equity, enabling founders and existing investors to hold on to more shares. It works well with a company that has strong unit economics but is looking to avoid a flat round or down-round.

Then when it comes to thinking about bringing debt to the equation compared to equity, Allen illustrates how the frames of reference differ for these two instruments. For equity, the frame of reference is the future. How can the company achieve a [insert period here] forecast so the dilution is balanced out by growth and everyone gets a win in the end? For debt, the frame of reference is current and past performance. How confident is the company in ensuring that this current state of cash flow isn’t going to get worse?

Allen emphasizes that debt isn’t suitable for companies with too many risk factors or that aren’t quite clear yet on all the moving parts in their model (e.g., early-stage companies that are still nailing product-market fit down). The company should be mature enough to have contingencies in place to handle the uncertainties of bearing on debt: “I don’t recommend [debt] for people who don’t really know their business because if too many things can go wrong and now you’re like, “Okay, it’s outta my hands and all that” –You should never say that. As a financial leader, you should say like, “Okay, these are the things that we’re preparing for and if that were to happen, then we have these contingencies.”

At the end of the day, regardless of the instrument the company decides on, the first principles here are to (1) have a deep understanding of the risks in one’s business (sounds intuitive but easily underestimated) and (2) already consider multiple options long before entering the fundraising market.

Paulo Joquiño is a writer and content producer for tech companies, and co-author of the book Navigating ASEANnovation. He is currently Editor of Insignia Business Review, the official publication of Insignia Ventures Partners, and senior content strategist for the venture capital firm, where he started right after graduation. As a university student, he took up multiple work opportunities in content and marketing for startups in Asia. These included interning as an associate at G3 Partners, a Seoul-based marketing agency for tech startups, running tech community engagements at coworking space and business community, ASPACE Philippines, and interning at workspace marketplace FlySpaces. He graduated with a BS Management Engineering at Ateneo de Manila University in 2019.