Edtech in Southeast Asia is entering a golden age. Opportunity for tech startups to cash in the sector has reached its inflection point with the convergence of three key factors: (1) a broken K12 general education system, (2) increased spending on the part of parents for learning supplements and after-school classes, and (3) more consumers familiar with ecommerce, digital payments, and other online services. Combined with the accelerated, forced adoption of online learning due to COVID19 response measures, there is a strong case for an edtech unicorn in Southeast Asia to be the primary provider of standardized, trusted, accessible and localized education to the K-12 population it serves in the region.

Many edtech founders and investors have questioned, argued and pondered upon what this winning model would look like in Southeast Asia. It doesn’t matter which entry point you choose; the winner will be one that captures the complete learning cycle of K12 students. In this essay, I share what capturing this learning cycle means in Southeast Asia’s emerging markets and how edtechs can think about their go-to market strategies.

Assessing the knowledge gaps

Unlike developed markets where the general education system is mature enough to be the primary source of learning for students, the education systems of most emerging markets of Southeast Asia have yet to play this role. Many emerging markets in Southeast Asia show similar structural issues in the education systems:

- Low education attainment especially towards tertiary education

- Teaching is on par in terms of man-hours but suffers from quality issues especially outside Tier 1 cities

- Skills gap arising from a shortage of homegrown talents especially in engineers.

To make up for these gaps, parents have traditionally resorted to subscribing their children to extra classes from a young age. For the wealthier family, children will get one-on-one attention from private home tutors. For the middle class, group tuitions are common and are typically conducted in highly fragmented private tuition centers across the country. These extra classes are geared towards reinforcing concepts taught at school, assisting students with homework, and preparing for upcoming exams.

Over the years, we have seen branded regional tuition centers like English First and Kumon gaining ground in local markets by leveraging on their home brands and the universality of the subjects they specialize in and providing standardized quality teachings. At the same time, unstandardized offline home tutors or small tuition centers continue to take a significant share of the pie, living off the value proposition they provide in terms of trust, accessibility and localization.

However, these supplementary classes remain limited in reach and scope. Rapid internet adoption and increasing familiarity with digital solutions (especially among the student demographic) offer a way not just to fill in the gaps of education systems but also do this at a scale with which offline tuition centers will not be able to compete. This is the opportunity ushering in edtech’s “Golden Age” in Southeast Asia. Class is in session for edtechs to make this “Golden Age” happen.

Mastering the learning cycle to strengthen gaps

The edtech that emerges at the top in the region will be one that captures the complete reinforcing learning cycle of K-12 students. The cycle is as follows (with no specific initial stage):

- Knowledge Gap Assessment: Students in the region typically leverage on tools or mock exams to access their knowledge gaps.

- Strengthening Knowledge Gaps: Then they seek learning materials either in the form of video or texts to strengthen those knowledge gaps.

- Practice and Application of Concepts: As students climb higher in the Blooms Taxonomy hierarchy, they seek avenues to practice questions and apply concepts learned.

- Reinforcement of Concepts: While live tutoring could step in at any point of this learning cycle as a facilitator in the journey, its true value is realized in reinforcing concepts of students.

Then the cycle repeats.

K12 Learning Cycle in 4 Stages rated according to distribution and monetization capacity. A unified edtech platform captures this entire cycle.

The beauty of this cycle lies in its openness for multiple entry points into the student’s day to day learning behavior. In China and India, we have seen unicorns starting off at various entry points in this learning cycle. YuanFuDao, for instance, entered the market with question banks (stage 3) and has since then built out other products that completes the cycle. India’s Byju entered the market with eLearning content (stage 2), ZuoYeBang with homework solutions (stage 2), GSX Techedu Inc with live tutoring (stage 4), and 17ZuoYe with study tools and analytics (stage 1). In one way or another, all these unicorns have launched products that capture a larger part of the learning cycle by the time they hit unicorn status.

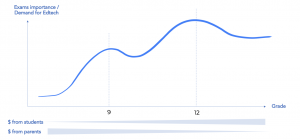

These models also all gear towards test preparation, which reflects the culture and paying habits of the China and India markets. This is similar to Southeast Asia, where test preparation has been key in pulling students towards edtech platforms and unlocking the first out-of-pocket spending.

Unlocking monetization by gearing up for test prep use case

That said, in Southeast Asia’s relatively young edtech market, the challenge facing founders in deciding a point-of-entry into the learning cycle lies between distribution and monetization. At the beginning of the learning cycle (stages 1 to 3) is where mass distribution happens, and monetization kicks in as the student progress towards the end of the cycle (stages 2 to 4).

The general rule of thumb for any edtech player is to be the category leader in one of the stages of a student learning cycle before moving on to the next. The winning model is able to eventually strike the balance in both distribution and monetization, while staying top-of-mind for students for anything education related. In order to do this, the edtech needs to become a unified edtech platform.

Applying the unified edtech platform approach to Southeast Asia

Comparing go-to market strategies for edtechs in Southeast Asia

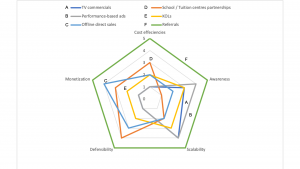

With increased ecommerce and digital payment penetration rates in Southeast Asia, the concept of learning online has become more familiar among students and parents in the region. When it comes to gaining awareness, performance-based ads have been effective in reaching students while TV commercials have been effective in generating buzz amongst parents. COVID19 has also certainly driven users to look for these online platforms.

While barriers to adoption have lowered, the trickiest part in Southeast Asia’s edtech landscape is monetization. Student behavior has been well-entrenched in going to offline tuition centers or superstar tutors. The key to converting free adoption to sustained out-of-pocket spending is trust, which parents and students place on brands. That means edtechs have to think creatively how to build their brands without draining too much on marketing. Offline direct sales appears to be the most effective in unlocking large out of pocket expenditure of parents, something which Byju in India did successfully. Meanwhile, referrals by an army of satisfied students can be the most effective in owning a recurring share of the student’s budget.

Reinforcing changes in learning and teaching

Even with edtech entering a golden age, the traditional K-12 schooling system is here to stay in Southeast Asia. Students will still go to school, be taught a standardized curriculum and undergo a form of assessment to graduate. What will change is the way students learn and the way teachers teach.

As unified edtech platforms gain more adoption in the region, students will spend a substantial amount of after-school learning time on these platforms, and teachers will deepen their integration of platform solutions into their teaching curriculum.

Reinforcing these changes in education will be a matter of developing data-driven feedback loops and scaling a tech layer beyond the limitations of traditional education. Over time, more customized solutions will emerge from these platforms as both students and teachers become more data-driven in their learning and teaching. Beyond the geographical barriers and human capital limitations posed by traditional K12 schooling systems, especially outside Tier 1 cities, edtech platforms can provide accessibility to learning beyond the four walls of the classroom.

Takeaways

- Assessing the knowledge gaps: Education systems in Southeast Asia have structural issues that prevent them from being the primary source of learning for students. Parents are then willing to pay for supplementary learning materials and afterschool programs to make up for these gaps, but these can still remain inaccessible and insufficient. Edtech is entering a golden age with digital consumption offering a better way to change the way students learn and teachers teach.

- Mastering the K12 learning cycle: The winning edtech model will be the one that captures the complete reinforcing learning cycle of K12 students. The model that is able to strike the balance in distribution and monetisation, while staying top-of-mind for students on anything education related, will be one that will win the market.

- Applying the learning cycle in Southeast Asia: GTM strategies in SEA is very different from developed markets. Offline direct sales appears to be most effective in unlocking large out-of-pocket expenditure of parents and referrals are most effective in owning a recurring share of the student’s budget.

- Reinforcing change in Southeast Asia: Even with edtech entering a golden age, the traditional K-12 schooling system is here to stay in Southeast Asia. What will change is the way students learn and the way teachers teach. Reinforcing these changes in education will largely be a matter creating data-driven feedback loops and enabling accessibility beyond Tier 1 cities.