Highlights

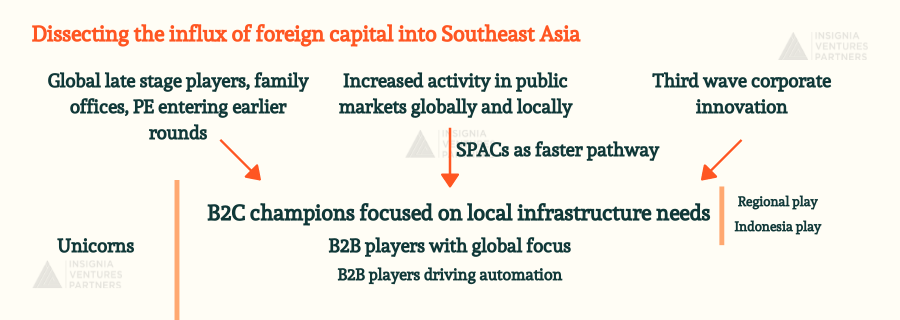

Where is the capital coming from?

- Late-stage players are coming in earlier rounds, creating a more complete investment value chain and pathway to exit for startups in the region.

- Increased liquidity in public markets (especially on Wall Street) picking up Southeast Asia’s unicorns and driving SPAC interest.

- Third-wave corporate innovation (CVCs set up by tech startups) driving scaling capabilities and M&A exit opportunities for startups in the region.

Where is the capital going? Funding is still dominated by B2C local and regional champions, but there is room for a few B2B unicorns with global scope.

L-R, T-B: Global Hands-On VC’s founding managing partner Ken Yasunaga, Adjunct Professor and Partner at CeTIM/GLORAD Martin Haemmig, Willett Advisors (Bloomberg family office) Head of Global Venture Capital Sherry Lin, Arbor Ventures managing partner Melissa Guzy, and Yinglan Tan

A significant part of Southeast Asia’s narrative as a tech ecosystem in 2021 has been this new wave of foreign capital entering the region, precisely because of the impacts of the pandemic on capital markets, technology firms, and digital adoption. In this year’s SuperReturn China conference, our founding managing partner Yinglan Tan joined Arbor Ventures managing partner Melissa Guzy, Global Hands-On VC’s founding managing partner Ken Yasunaga, and Willett Advisors (Bloomberg family office) Head of Global Venture Capital Sherry Lin on a panel that covered this influx of foreign capital into the region, be it from family offices and global VCs or corporate VCs, and the implications of this rising interest in Southeast Asia for the exit and scaling of homegrown players. The panel was moderated by Adjunct Professor and Partner at CeTIM/GLORAD, Martin Haemmig.

As we do with every panel we have the pleasure of joining, we covered the important points from their discussion and curated them into the piece below. For more event notes and coverage, check out these past articles.

Late-stage players are coming in earlier rounds

Global investors are placing their bets in the ring of Southeast Asia in earlier stages, like Series A and B rounds, whereas the Softbank’s and KKR’s of the world in the latter part of the 2010s have focused on late-stage plays. One example mentioned by Sherry Lin was Accel Partners coming into Xendit’s Series B, another was Valar Capital investing in Syfe’s Series A.

And the same trend of favoring early-stage investments is also becoming more popular among LPs and family offices, over the approach of entering late-stage at a point when valuations have ballooned. Sherry adds, “[There was certainly] the Softbank effect four or five years ago, [but since then] we have had a more wary view of growth…We have shifted more towards the early stage and growing with the early stage because they create that funnel or net for LP investors like us, and they have that special seat at that later growth stage. We’ve backed away from just pure growth players.”

This trend of typically late-stage investors extending their play to direct and indirect investments in early-stage companies will better link up the value chain of early-stage and late-stage investors in the region, creating a more complete pathway for startups to go from seed to exit.

Public markets picking up Southeast Asia’s unicorns

And when it comes to exits, there’s also a significant shift happening in Southeast Asia, where the M&A-dominated region is seeing greater validation in the public markets. Investors are seeing that it’s possible to build many more billion-dollar companies in the region that can convert into the hundred billion dollar plus outcome that Sea Group has achieved. And more pathways are opening up with SPACs, and even regional exchanges like SGX and IDX are becoming more forward-looking in terms of encouraging local tech companies to list. This shift will be carried largely by the increase in liquidity heading to the public markets, both from institutional and retail investors, that have found attractive destinations in Southeast Asia unicorns. The lower interest rates in the region (cost of investing in this case) also help.

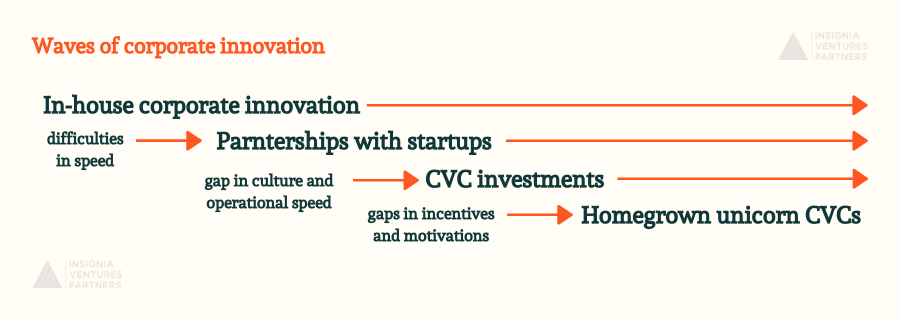

Third wave of corporate innovation driving scaling capabilities and M&A exits for startups in Southeast Asia

But even in the M&A space, Yinglan notes that there are tailwinds from a lot of Chinese Japanese, Korean companies trying to expand their footprint in Southeast Asia, opening up more exit pathways for startups in the region. “So a lot of them are trying to do targeted acquisitions or even very large acquisitions or Joint Ventures,” he adds.

At the heart of Southeast Asia’s M&A space is corporate innovation. With many startup narratives revolving around disrupting traditional corporates, it is also worth noting that corporates are often the progenitors of tech ecosystems. While corporates seek to drive innovation internally first, they realize that it would be more cost-efficient to work with startups and cultivate the growth of the local ecosystem to meet their needs. Sherry adds, “Usually you see the corporates come in first because they’re strategic. They have a reason to be there. As the ecosystem develops [the players become] usually homegrown.”

But as corporates partner with startups, some also realize that direct collaboration can be difficult to navigate with the massive gap in culture between startup and corporate organizations. This opens up doors to invest not just in startups but also in funds through corporate development offices and corporate venture capital funds, though Yinglan notes that corporates venturing into investing has not always turned out well in Southeast Asia. “Results have been mixed like some of these corporate venture funds get shelved after two, three years,” he says. And this could be attributed to a variety of factors, but oftentimes even with the CVC approach giving startups freedom, there has been a tendency for corporate investors to seek control, if not in terms of the business itself, then on the cap table, through veto rights, board seats, and significant stakes, which could easily turn founders and prior investors off especially if there are no significant synergies or clear exit path down the line. But Yinglan also adds, “I think we are seeing a new wave of CVCs that is very interesting.”

And this wave he is referring to is the formation of CVCs and corp dev offices by the very homegrown unicorns that were also partly backed by other CVCs. The prime example in Southeast Asia is Sea’s recently formed billion-dollar corporate fund to invest in adjacencies to the Sea ecosystem. These CVCs coming from homegrown unicorns have the best of both worlds: the scale and ecosystem of a corporation alongside the understanding of what founders and startups go through as well, which could be a key asset on the cap table of startups.

In that way, Sherry Lin adds that Southeast Asia is a little bit more developed than more mature markets like Korea for example. “We still see in Korea that a lot of the venture activities are done by corporations and more the old-line corporate. There are very few kinds of the local homegrown [venture funds].”

But regardless of the kind of CVC, if they invest in the right startups, they can be valuable investors, in more ways than one, from helping build the company, supporting regulatory navigation, and providing a means of exiting. Arbor Ventures’ Melissa Guzy, whose focus is largely on fintech, shares that CVCs have been in fintech from the very beginning. “I think every single one of our companies in Asia has a corporate VC as an investor. And they came in quite early, but that has been true of the US and also of Israel…If you look at the InsureTech portfolio, you almost have to have an insurance company in there as an investor to actually progress…this has been going on in FinTech for a very long time.” This has been the case to the extent that it’s an unspoken rule to have a CVC investor on a fintech’s cap table, as the insights of a more established financial institution, especially a global one, will be useful for fintech startups at a time of increasing and enhanced regulation in financial services across the world.

That said, for both founders and investors already on the cap table, it is important to still be conscientious of CVC motivation when entering a round, whether it is strategic, simply part of their investment thesis, or purely a financial initiative on their part — and what this motivation means for the level and kind of value add they will bring to the table. Melissa adds, “The key is to make sure you don’t develop a product specifically for them. And also there’s always the potential for competition from them down the road. So it’s a balancing act as to who comes in, when they come in, what value they’re going to be providing to the company.”

Another value-add for CVCs and corp devs coming into the picture can be to help startups internationalize or regionalize, and scale beyond their home market. Global Hands-On VC’s Ken Yasunaga points this out as he explains the role of a venture capitalist in supporting startups as they go international. “The VC’s role is mentoring, coaching, networking introduction, [and] bringing some of the international corporate venture capital firms. [For example], I have brought Google and Nvidia to one of my portfolio companies. So that has a tremendous value…”

But internationalization and scaling across markets will take more than a supportive VC and a lineup of global CVC backers. As Melissa Guzy explains, “Internationalization requires a very experienced CEO and it usually requires a certain entrepreneur to be able to handle it, especially if they go on day one.” And not all types of businesses lend themselves to going global. Some verticals like payments will hit a hard regional or country ceiling as they scale simply because of the incongruencies in infrastructure and regulations across markets. And going global will take a lot of time as it did for companies like Visa. “So we believe in regionalization as well as internationalization, but you got to know what you are and what you have as a product,” adds Melissa.

With Southeast Asia typically producing two kinds of scaling trajectories — a regional play or Indonesia play — the presence of more foreign capital and CVCs to support scale could see more startups trying to make a third trajectory more commonplace: that of going global.

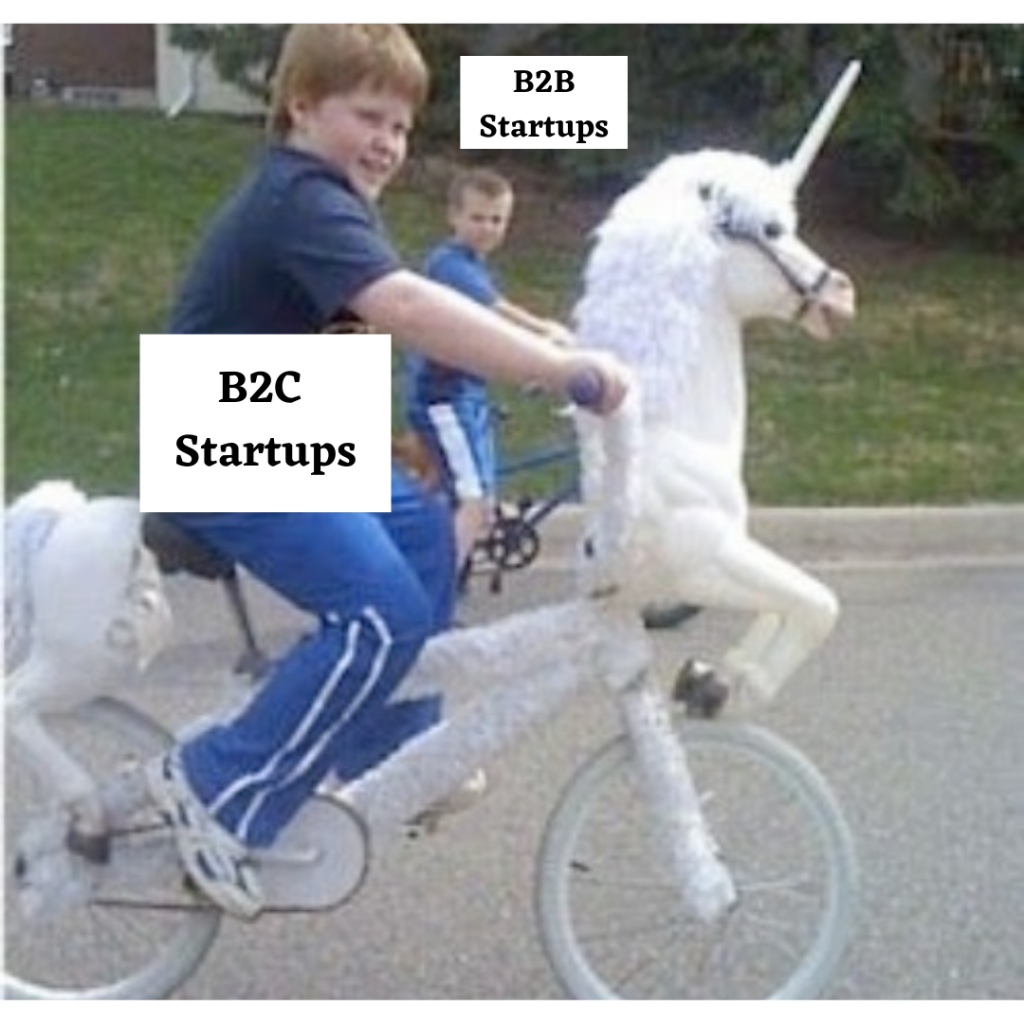

Next-generation unicorns to continue filling in region’s infrastructure gaps with B2C models, but a few could come from a new wave of B2B digitalization

As the 2010s generation of unicorns has drawn in greater investor interest into Southeast Asia, these very investors are also beginning to explore what types of businesses will dominate the region’s unicorn club in this decade.

Southeast Asia as an ecosystem is still in this phase of supporting the emergence of local, national, and regional champions to cover key infrastructure needs for an internet economy to fully flourish. Whereas more developed markets are more focused on the shifts in technology itself, emerging markets like Southeast Asia are focused more on laying the groundwork for these shifts in technology to be possible and widely adopted. And this phase of laying infrastructural groundwork — from payments infrastructure to logistics networks to last-mile insurance distribution and healthcare services — is best achieved by companies with a local advantage.

Melissa Guzy echoes this take from a fintech perspective, “So in developed markets, it’s more about the transformation to cashless…and then when we look at emerging markets, such as Southeast Asia, it’s a lot more about financial inclusion and actually putting the infrastructure in place that doesn’t exist today. When you’re looking at companies more in Southeast Asia, they’re really being developed for the local markets, which have a lot of nuances that are not understood by international companies. And that’s why you’re going to see local champions.

And laying this groundwork for more consumers to access critical services means that many of these emerging champions will be B2C companies. The B2B companies that do exist in the region and have raised funding will still likely have to find a wider customer base beyond the region to raise their valuation to a unicorn level. That said, as the GDP per capita continues to rise in markets in the region, the cost of labor will go up and automation will be preferred, first by the larger companies, then it will trickle down to smaller businesses. And we are already seeing the early emergence of B2B and SaaS companies catering to this need in the region.

Yinglan adds that alongside the continued emergence of B2C localized champions as unicorns in Southeast Asia, there “may be one or two [unicorns] headquartered in Singapore, but targeting the global market.”

Paulo Joquiño is a writer and content producer for tech companies, and co-author of the book Navigating ASEANnovation. He is currently Editor of Insignia Business Review, the official publication of Insignia Ventures Partners, and senior content strategist for the venture capital firm, where he started right after graduation. As a university student, he took up multiple work opportunities in content and marketing for startups in Asia. These included interning as an associate at G3 Partners, a Seoul-based marketing agency for tech startups, running tech community engagements at coworking space and business community, ASPACE Philippines, and interning at workspace marketplace FlySpaces. He graduated with a BS Management Engineering at Ateneo de Manila University in 2019.