Interview with Yinglan Tan for Nikkei Asian Review piece on the Philippine startup ecosystem.

Why is the Philippines’ lagging behind when it comes to deal-making and capital-raising activities for start-ups in Southeast Asia? Is it the regulation? Quality of start-ups?

With 6.55 real GDP growth in 2018 and a population of 107 million, the country holds great potential to be the next rising ecosystem. To put it into context within the region, Indonesia is like the King, Vietnam the Queen and Philippines is the Jack. The level of deal-making and capital-raising activities in the Philippines are a direct effect of the overall health the country’s startup ecosystem. There are certain changes in the ecosystem which need to happen before Philippines can reach the heights of Indonesia and other countries.

Institutional support

A 2017 PWC study on Philippine’s startup ecosystem reported that there are more than 300 startups in the country and over 200 of them are actively operating. There are notable incubators, accelerators and early stage VCs such as ideaspace and Kickstart. However, there is a gap in institutional support for post-Series A startups where significant capital is needed to help the startup grow and cross the chasm. Startups at this stage reach a significant scale where many internal changes take place within its team, culture and processes.

Regulatory support

Up until recently, there has not been a coordinated effort to lay the foundation to a vibrant startup ecosystem in the country. The collaboration between the Department of Science and Technology (DOST), Department of Information and Communications Technology (DICT), and the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) should produce a roadmap to coordinate support efforts from different pockets of the ecosystem. Initiatives such as targeted regulatory sandboxes would help open up resources from the government and corporations while protecting startups from competition.

A key factor amongst this would be political stability. This would help ensure long-term foresight in policy planning and continuity in the initiatives implemented for the community.

Talent and human capital

Education is still geared towards the service industry rather than entrepreneurship or the creative economy. Many graduates aspire towards corporate jobs or Business Process Outsourcing (BPO) companies with attractive and stable paychecks. Aside from this, brain-drain is still a significant trend and Philippines has yet to experience the same influx of highly-educated returnees (海龟s) witnessed in other countries.

There is a limited set of rockstars that aspiring entrepreneurs can look up to and success stories are limited to first movers in fintech or HR solutions. There hasn’t been a success story which has reached the levels of Go-Jek in Indonesia and this impacts how far local startup founders in the Philippines dare to aim beyond their local market. Founders are generally conservative when it comes to how they look at growth.

Industry support

There is a general lack of widespread industry support which has until recently been largely dominated by the telcos. This has affected the nature of startups which succeed in the country. Infrastructure support and resource access have to open up to ensure that development can progress beyond major cities and into second and third tier cities.

As a foreign investor, what do you want to see in the Philippines in order for you to invest?

Critical mass of entrepreneurship and startup activity

The base level of entrepreneurship and startup activity (i.e. the propensity for talents to create new businesses or work in young companies) have not reached the same heights as what is currently witnessed in other parts of the region.

This is directly linked to the talent pool in the country, be it technical talents or talents with business backgrounds or industry expertise. A deep pool is needed to fuel the growth of startups. In addition, it can produce a generation of founders / entrepreneurs with the grit and smarts to innovate new business models, create new products and solve complex problems in the market. In contrast to the current brain-drain phenomenon, the country should also start witnessing a trend of highly-educated returnees (海龟s) returning to start new businesses.

Openness of the startup ecosystem and capital markets

There are already pockets of activity in different parts of the local startup ecosystem. It is critical that efforts are made to coordinate and link up the ecosystem. In addition, an active startup ecosystem needs to be open in order for new local players and other foreign stakeholders to easily participate and connect resources. This is especially critical if the goal is for local startups to ultimately expand into other markets in the region.

The government’s stance and regulatory attitude are important factors in sending a message to foreign investors that the country is ready to open up. This includes policy changes to make it easier for foreign capital to flow into local companies by easing foreign ownership limits in specific industries. Other important areas include creating clearer regulations and simplifying regulatory approval and other legal corporate processes.

Possibility of profitable exits and corporate-startup partnerships

Ultimately, foreign investors also need market evidence that the ecosystem is mature enough to support the growth of mid-market companies and attractive investment returns can be made. The best evidence would come from the emergence of the first generation of successful thriving startups valued US$100M and above.

Corporate-startup partnerships are key to helping the country to reach that stage. There are already large conglomerates specifically in real estate, retail, telcos, banking, energy and insurance. These industries have potential for partnerships including acquisitions, buy-outs and strategic investments which can boost tech companies and further spur the local economy.

What are the chances that Philippines can still catch up at least in the latest or next wave of tech innovation?

Is there still an opening for Philippine start-ups in a region already dominated by growing number of unicorns in Singapore and Indonesia?

With its population and growing middle class, Philippines definitely has a large enough market to produce a unicorn – either a horizontal platform or a player focused on a sufficiently large vertical. The local market also has its own unique set of intricacies to support a local champion, i.e. “mutants” that adapt successful business models in the region for local differences.

Take the fintech space for example. The regulation, underwriting environment, attitude towards credit and trust towards tech startups as business partners differ from market to market. Thus, market-specific customer on-boarding processes, proprietary underwriting models and highly localized datasets are key to winning each market. This creates the opportunity for local champions like First Circle to create a superior product over foreign entrants entering the local trade financing space.

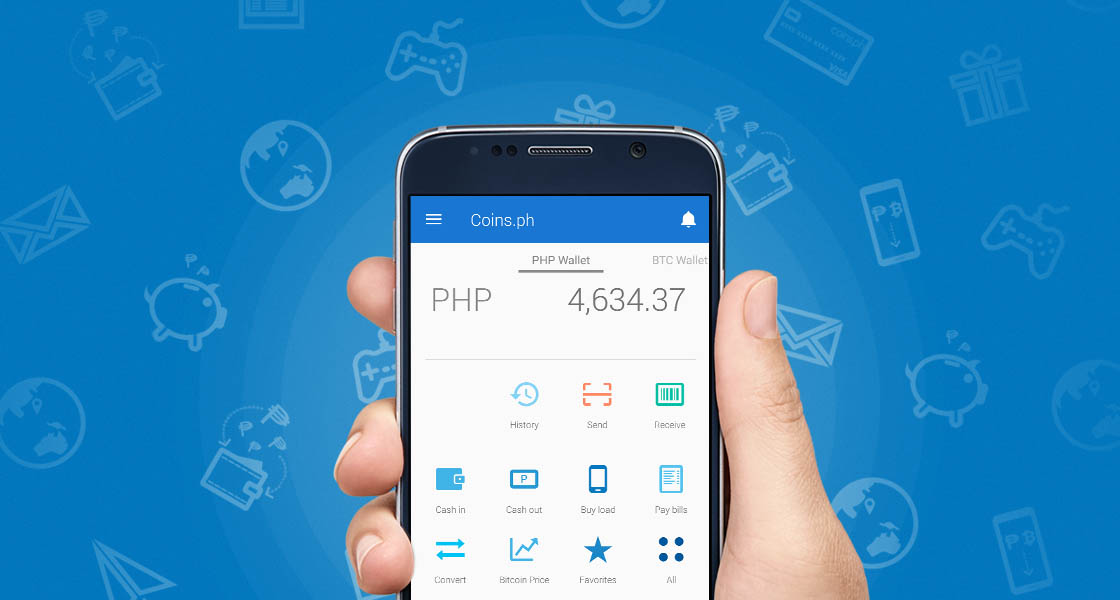

Image of Coins.ph app. Image taken from Coins.ph

The active participation by regional and global tech giants in the country is a clear evidence supporting this. This includes Gojek’s “substantial investment” into Coins.ph, Tencent and KKR’s investment into Paymaya and Ant Financial’s investment into Mynt. What the Philippines needs is a generation of startups (US$100M valuation and above) that have been around for 3 – 5 years, crossed the chasm with its initial product and are rapidly expanding into adjacent services or markets.

In recent years, the Philippines has been working on its ecosystem fundamentals, highlighted by the formation of support systems like the Department of ICT, QBO (a PPP initiative for startups), and VCAP (Venture Capital and Private Equity Association of the Philippines), the active involvement of legislation through the Philippine Startup Bill and the One-Person Corporation, and the launching of “sandboxes” for entrepreneurs like in PhilDev, Ideaspace, Founders’ Institute, Globe Future Makers, among others. However, these efforts are still concentrated in the early stage and do not address the missing growth stage where startups are scaling up towards mid-market and becoming a unicorn.

The above foundational initiatives can lead the way for support from more diverse sources. This includes attracting regional VCs to place a bigger focus and allocate more capital to invest in the country, encouraging corporate participation from a wider set of local conglomerates (beyond telcos and banks) either through CVCs or by funding local VCs, and getting HNWIs and family offices (e.g. old Chinese families in the Philippines) to start looking at startup investments. Participation from foreign conglomerates (Japan and Korea) can play an important role as a source of Foreign Direct Investments.

Beyond funding capital, support also needs to come in the form of technological infrastructure (5G and stable mobile networks beyond the major cities) and education to create a deep talent pool. Also, the government has to create incentives and actively make efforts to woo the Philippine diaspora overseas to return to the country.

Disclosure: Insignia Ventures Partners is an investor in First Circle. This article was developed with the assistance of Allen Chng and Paulo Joquiňo.

Yinglan founded Insignia Ventures Partners in 2017. Insignia Ventures Partners is an early-stage technology venture fund focusing on Southeast Asia and manages more than US$350 million from sovereign wealth funds, foundations, university endowments and renowned family offices. Insignia Ventures Partners is the recipient of two back-to-back “VC Deal of Year” awards for Payfazz (2019) and Carro (2018) from the Singapore Venture Capital and Private Equity Association and its portfolio include many other technology leaders in Southeast Asia. He also co-hosts the On Call with Insignia Ventures podcast, where he chats with portfolio founders and regional investors. An author on venture capital, startups and innovation, he recently published his fourth book, Navigating ASEANnovation (World Scientific, 2020). He also serves on the International Board of Stars – Leaders of the Next Generation, the Singapore Government’s Pro Enterprise Panel and is a Board Member at Hwa Chong Institution.