Highlights

- Last mile logistics is the cornerstone of all ecommerce journeys so impetus is even stronger to improve these journeys. In fact, we are seeing an increasing number of ecommerce journeys which only consist of the last mile, such as food deliveries.

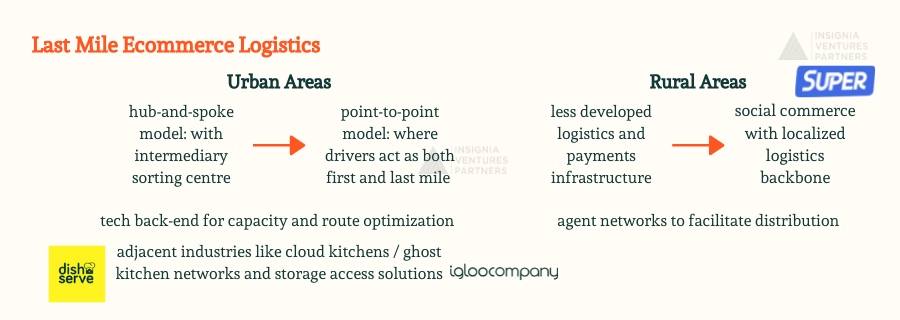

- When ecommerce first came to the region, the last mile came in the form of a hub-and-spoke system, which we had previously described, instead of being point-to-point. While under the hub-and-spoke model, parcels to your next-door neighbour would have to pay a visit to the sorting centre, these new point-to-point players have intelligent systems combining the first and last mile.

- In rural areas, this last mile comes in the form of social commerce, where logistics and online payments are less developed, giving rise to an agent model.

We end our Ecommerce Logistics series with a look at the last mile, which is the most developed leg of the Ecommerce Logistics value chain in Southeast Asia. Especially during this new normal where consumers are increasingly shopping online, the last mile has been undergoing even more robust growth. Same or next-day delivery is no longer a ‘good-to-have’ value-add to customers: it is today the expected level of service standard from the now-pampered Southeast Asian online shopper. For online sellers looking to displace Amazon Prime, it is imperative to ensure a robust last mile: it needs to be speedy and affordable, as shoppers are less willing to pay for shipping, and are becoming increasingly impatient.

The Last Mile Exists in all Forms

In our previous two articles, we’ve traced the journey of our ecommerce parcel, from leaving the place of fulfilment, whether picked up from your seller or from an outsourced fulfilment centre, straight to sorting centres, before hopping on a truck or plane or ship. The whole process is very symmetrical: by and large, the last mile is indeed very similar to the first mile. From the very last sorting centre, our parcel will trace the reverse-opposite of its first leg, now hop onto the back of a van, tuktuk, or even in the backpack of your delivery man onto your doorstep.

As the name implies, Last Mile logistics refers to the final step of the delivery process from the last distribution/sorting facility to the customer. This is the most varied step of the ecommerce logistics supply chain and is where we have seen the most innovation- the last mile can be anything from being two streets away in urban areas, or even 20-30 kilometres away in rural places. McKinsey and Company has valued the last mile at over US$80bn and accounts for over 53% of ecommerce logistics costs in our region. Last mile logistics is the cornerstone of all ecommerce journeys so impetus is even stronger to improve these journeys. In fact, we are seeing an increasing number of ecommerce journeys which only consist of the last mile, such as food deliveries.

Urban Journeys: Moving from Point-to-Point

The past five years have seen a rapid development of the last mile, where a new ecosystem has risen from ground-up. This rapid network had been formed between sorting/distribution centres towards consumers’ doorsteps, allowing for a large volume of small parcels to travel at great frequencies enabling next-day and even same-day delivery. In the urban scene, we see minivans, motorbikes and even walkers plying routes around our streets, enabling our new normal of online shopping.

When ecommerce first came to the region, the last mile came in the form of a hub-and-spoke system, which we had previously described, instead of being point-to-point. This meant that deliveries within the same city would follow the first-middle-last journey, where a parcel would be picked up, sent to a sorting centre before being dropped off. Where many traditional players used this model, it gave rise to technologically-enabled players such as Ninjavan and J&T, whose drivers act as both the first and last mile. Parcels and their destinations are accounted for digitally, both allowing for better traceability (minimising lost parcels), but also helps with dynamic routing. So while under the hub-and-spoke model, parcels to your next-door neighbour would have to pay a visit to the sorting centre, these new point-to-point players have intelligent systems combining the first and last mile.

The rise of point-to-point delivery for the urban last mile is more pronounced than we think. This is most prominent in the rise of food delivery during the coronavirus, which adopts the same concept: your food would be both picked up and delivered by the same person from point-to-point. In fact, we internally estimate 3 in 4 last-mile deliveries in Tier 1 cities are food and grocery deliveries. The technological back-end is especially difficult, not only having to dynamically find the best route for both pickups and drop-offs, taking into account capacity in vehicles, but also having to navigate traffic regulations and even finding places to park.

This has since given rise to adjacent industries such as cloud kitchens and ghost kitchen networks (such as DishServe). With ecommerce deliveries now much cheaper, we have seen other innovations such as delivery lockers at apartment buildings, and even smart lockboxes at doorsteps (which IglooHome piloted as early as 2015). In the future, we hope to see robots and even delivery drones making deliveries, as we are already seeing these in fulfilment and sorting centres.

Rural Areas Need a Last Mile Too

In other areas, this last mile comes in the form of social commerce, where logistics and online payments are less developed, giving rise to an agent model.

Super provides rural Indonesians with better access to goods through a social commerce model, which is especially made possible with a robust last-mile logistics system catering to unique local circumstances. In rural Indonesia, and as we have also seen in most of Southeast Asia, most residents do not have access to online payment methods, but mobile penetration and internet usage is high: warungs and other sellers communicate with their customers via Whatsapp, which is where over 80% of new product discovery occurs.

At the same time, they live in kampungs without street names, which is a crucial data point required by last mile delivery providers. In response, Super’s disruptive last-mile solution uses “Agents” (typically people from the very communities they serve) to serve as a bridge aggregating the needs of their communities through group buying to provide both a last-mile delivery and payment solution. Reducing costs in rural areas is increasingly important- there are two folds to this. It is not only crucial to ensure that the cost of basic necessities are kept low for rural households, but also ensures that every dollar saved in logistics is passed onto the agents themselves, as a crucial source of income.

The Last Mile but the First Priority

Going back to our initial point, last mile logistics is the cornerstone of all ecommerce journeys and impetus is even stronger to improve these journeys. In fact, we are seeing an increasing number of ecommerce journeys which only consist of the last mile, such as food deliveries. Nonetheless, as a share of the total cost of shipping, last mile delivery costs are substantial, representing over 53% of ecommerce logistics costs. Today consumers are not only demanding quick delivery, but essentially also “free shipping,” where sellers are increasingly having to subsidise logistics cost.

It has therefore become imperative that current players have sought to implement new technologies and drive process improvements – in fact, some ecommerce journeys only consist of the last mile. Moving forward, we will continue to see even more technological improvements in the last mile to further reduce costs, increase speed, and expand capacity.

Russell is excited about the power of innovation improving lives across Southeast Asia. An ex-founder from the London McKinsey Venture Academy, Russell is now looking for daring new founders in Southeast Asia. Drop your pitch at russell@insignia.vc.