Highlights

- As capital markets dry up and the value of cash is being impacted, investors and founders are increasingly incentivized to diversify the value of investments beyond capital.

- The reality behind pivots is that they are rarely built from square one. Things have to add up from the business side prior to the pivot for the pivot itself to make sense. And from the perspective of the VC-founder relationship, it’s all about putting these pieces of the equation together.

- Portfolio management through a pivot is not just about pointing out a new north star to follow but actually supporting the implementation of this course change.

- There are many layers to how venture capital firms are able to help on the people side of the company building equation, where arguably the multiplier effects are greater than any other type of value add…it revolves around the venture capital firm’s ability to attract the right talent with the right experiences and skillsets.

In a previous piece we wrote about the conundrum of scale for venture capital firms in Southeast Asia, in response to the HBS case study abstract on Insignia Ventures. In that article we discussed broadly about portfolio management as an equation that includes more than just dry powder for follow-on capital, which we can expect to increasingly be deployed towards existing portfolio companies as investors shore up their positions and founders tap into their cap table for further funding, as opposed to betting all in the fundraising winter today.

This time around we dive into the two examples included in the case of how Insignia Ventures worked closely with founders from an early investment to navigate pivots, scale, and evolution in their business’s respective markets. This discussion is even more relevant today where the value of cash/money is being impacted (i.e., valuation drops and investment cost markups) and sees no sure sign of any significant recovery in the next few years, meaning investors and founders are hard pressed to diversify what long-term investments really mean.

The case is now available for public access on the Harvard Business Review store and for Harvard educators and students on Harvard Business School Publishing.

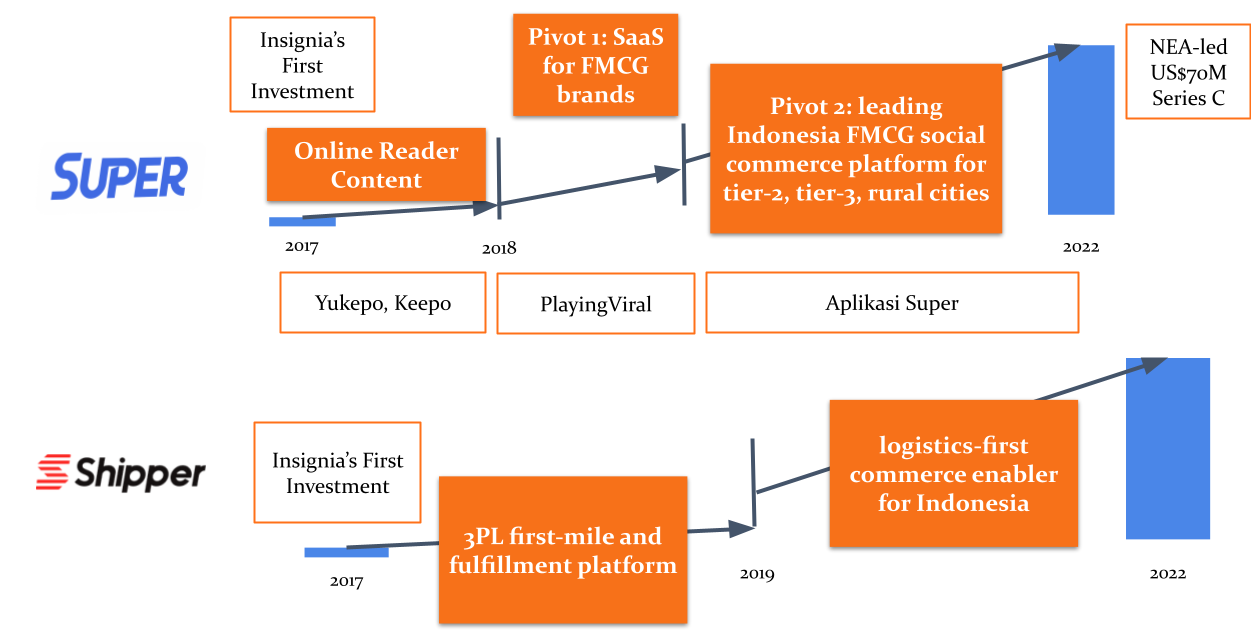

The portfolio companies highlighted are Indonesian social commerce platform Super and Indonesian logistics-first commerce enabler Shipper, and in this article we briefly recount the key highlights of these companies relationships with Insignia Ventures and focus more on the learnings for investors and VCs from the dynamics between investor and founder, with some citations from the case itself.

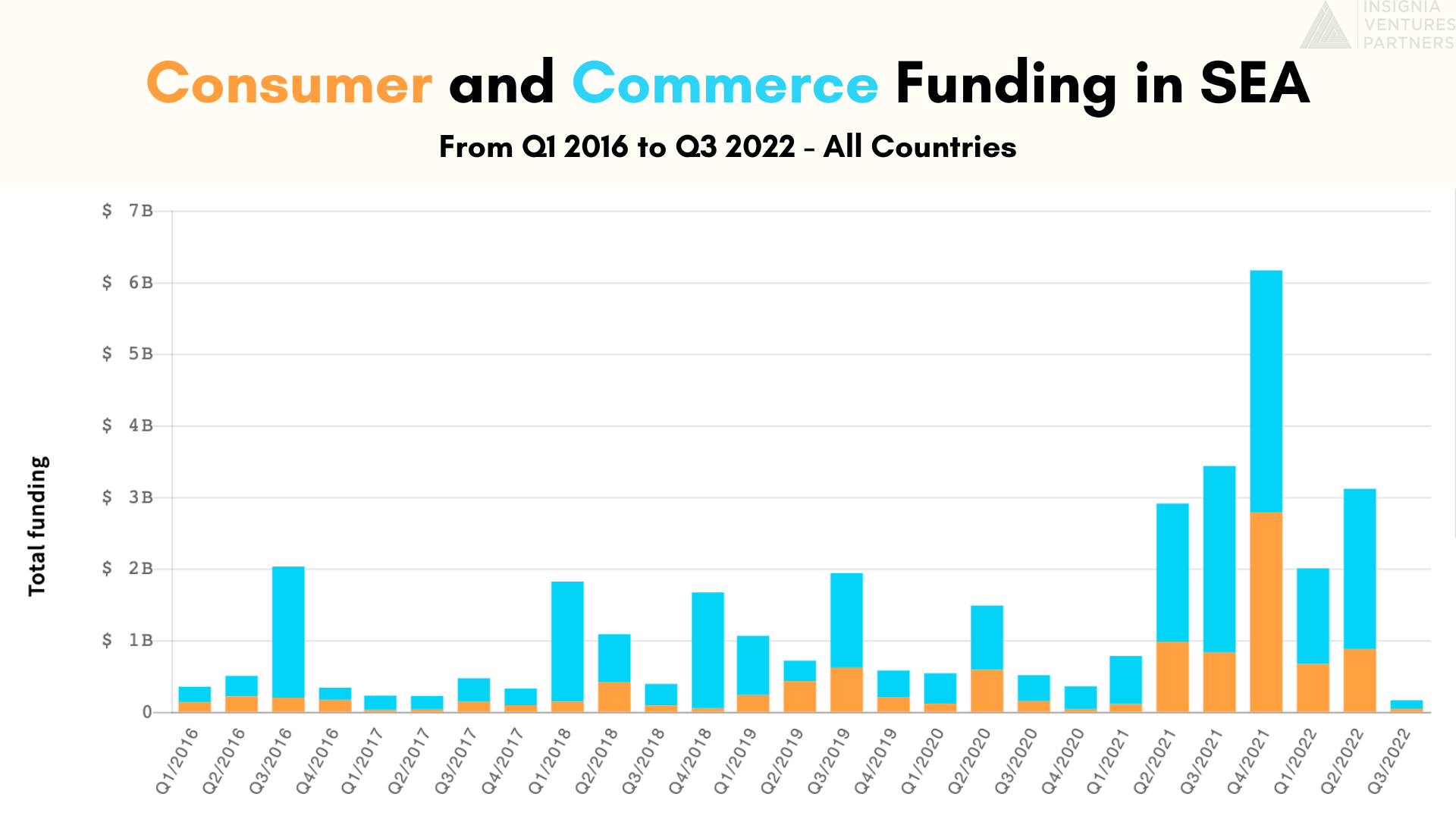

Data from insignia.vc illustrating funding into sectors across Southeast Asia covered by the two companies

The Super Case: Unlocking growth with market discovery on several levels

Super is Indonesia’s leading social commerce platform for tier-2 and tier-3 cities, and rural areas, leveraging a hyperlocalized supply chain of warehouse centers, local distribution hubs, and most importantly, agents or SuperAgen who facilitate group buying, to create more equitable and greater access to FMCGs for these geographies in Indonesia.

It’s not about “Eureka” moments but a “Eureka” build-up

However, the team behind Super did not initially start off in social commerce. When Co-founder and CEO Steven Wongsoredjo returned to Indonesia around 2016 after finishing his Masters in Columbia University, he founded Nusantara Technology, a company that first started out building media platforms Yukepo and Keepo, then pivoted to build an interactive advertising SaaS product PlayingViral. With this ecosystem of media and advertising products, Super raised its first institutional rounds of funding and also entered into Y Combinator Winter 2018 Cohort.

As they launched PlayingViral for companies to have better user engagement and agent-led sales distribution, Steven and his team discovered the larger market and monetization opportunity in becoming the primary point of distribution for end-consumers, especially in rural Indonesia where there have been longstanding issues in access to goods Steven was very familiar with growing up with a family retail business in rural eastern Indonesia. Nusantara Technology could become the agent network themselves rather than just making money off margins of their SaaS advertising product and just enabling other companies to use the agent network approach for advertising.

The case cites some market observations that “paradoxically” pointed towards to potential of disruption, like low ecommerce adoption making something like social commerce more viable to scale. “Market observations the firm picked up growing PlayingViral also pointed towards the opportunity of addressing commerce and logistics inefficiencies in rural Indonesia. While internet penetration rates were incredibly high throughout both rural and metropolitan Indonesia, most users used this connectivity to simply access social media. Very few, especially those outside of the largest cities, made purchases over the internet. As he studied this seeming paradox, Steven grew to appreciate the highly trust-based nature of the Indonesian economy. Consumers were far more willing to purchase from merchants they knew and trusted rather than from those they met through online storefronts.”

Above passage taken from Lerner, Josh, and Richard Zhu. “Yinglan Tan: Scaling a Venture Capital Firm in Southeast Asia.” Harvard Business School Case 823-025, July 2022, page 7.

By this time, Insignia had already made its first investment into Super, and what Steven and his team saw as an opportunity to own the distribution of these goods themselves the firm saw and framed as “social commerce.” As part of their thesis development and market research, the VC firm was already looking into how social commerce might translate into a market like Indonesia, having studied the likes of Pinduoduo in China or Meesho in India.

Now the reality behind pivots is that they are rarely built from square one. Things have to add up from the business side prior to the pivot for the pivot itself to make sense. And from the perspective of the VC-founder relationship, it’s all about putting these pieces of the equation together.

In the case of Super, those pieces included: (1) market opportunity for disrupting (not just enabling) FMCG distribution in rural Indonesia, (2) Steven’s background and familiarity with operating retail distribution precisely in rural Indonesia, (3) higher propensity for rural communities to adopt social commerce, (4) stability and profitability of Nusantara’s existing businesses (i.e., resources were available to make the shift), and (5) support of Super’s investors in this pivot.

Supporting Pivots don’t end with the Pivot

Rather than a particular “eureka” moment for Steven, this was a “eureka” build-up that eventually led to the pivot into Super. This pivot has since panned out successfully for Super, with their latest Series C round led by New Enterprise Associates raised on top of the market leadership they built in Eastern Indonesia and their expansion further across Indonesia and even across other SKUs beyond FMCGs through white label products.

The case dives into what this pivot has meant for Super building up their competitive advantage in a market that, while nascent, was slowly populating with players as well. “This moat evolved to be the company’s approach to leveraging existing infrastructure in their target markets, for example working with housewives and community leaders as agents (who are themselves incentivized by the supplementary income) as well as local stores to serve as micro-fulfilment hubs or Super Centers. Leveraging existing infrastructure has not only helped the company reduce go-to-market costs but has also supported local economies and strengthened retention of their platform in these communities. From a competitive landscape perspective, the inherently cash-intensive nature of commerce and logistics, especially in a market with little to no infrastructure, made Super stand out with its unique approach.”

Above passage taken from Lerner, Josh, and Richard Zhu. “Yinglan Tan: Scaling a Venture Capital Firm in Southeast Asia.” Harvard Business School Case 823-025, July 2022, page 7.

For Insignia, portfolio management through this pivot was not just about pointing out a new north star to follow, but actually supporting the implementation of this course change through business model and market learnings. These insights and information ultimately helped Super to develop its moat in a hyperlocal supply chain and restructure this supply chain to reduce long-term risks for the business.

Combined with follow-on participation in the rounds that followed affirming conviction in this social commerce direction, Insignia’s support in the pivot extended well beyond the pivot itself.

The Shipper Case: Unlocking growth with people from all angles

Shipper is Indonesia’s leading logistics-first commerce enabler platform, providing end-to-end digital supply chain solutions for businesses of all sizes, as well as other digital tools for commerce businesses. The company connects customers through their proprietary software to the largest tech-enabled logistics network of 3PL providers, first-mile delivery agents, micro-fulfillment hubs, and warehouses across the country.

But Shipper didn’t start out as expansive in terms of its depth of services and breadth of customers. Serial entrepreneur Budi Handoko returned to Indonesia after several years in Australia and sought to solve the pain points he had experienced firsthand as an ecommerce seller navigating package fulfillment and working with 3PLs. He and his early team launched a 3PL aggregator platform in 2017, which Insignia invested in that same year.

Soon, Shipper began to expand beyond online platform aggregation and become part of the equation itself through a first-mile agent-driven logistics network and micro-fulfillment services. Late in 2018, the company was looking to expand further into larger warehousing capabilities and enablement.

Several Dimensions of People Value-Add Achieved By Becoming a Platform for Talent

Around this time as Shipper was looking to unlock its next phase of growth, Phil Opamuratawongse had come back to Southeast Asia from Floodgate as Chief of Staff at the Silicon Valley venture capital firm. He was looking to start his own company and briefly joined Insignia Ventures as an Entrepreneur-in-Residence to map out opportunities and find where he might best lend his experience and skills.

The case traces Phil’s journey from Southeast Asia to Silicon Valley and back again, and Insignia’s role as matchmaker between himself and Budi. “Though he grew up in Thailand, Phil Opamuratawongse moved to California at a young age. He completed a bachelor’s in mathematical and computational science at Stanford and a master’s in operations research from Columbia. He then worked for two years at McKinsey before taking on a role as Chief of Staff at Floodgate, a venture capital firm based in Palo Alto and run by Mike Maples Jr. After about a year and a half at Mike Maple’s side, he sought to try something new. Phil met Yinglan and joined Insignia as an Entrepreneur-in-Residence, with the intention of starting a company. During the stint and at Yinglan’s encouragement, Phil spent time with Shipper and developed a friendship with Budi. Insignia played the role of matchmaker and Phil decided to move to Indonesia at the beckoning of Budi, and also due to the emerging market potential, and the strong foreign interest in a nascent venture capital ecosystem.”

Above passage taken from Lerner, Josh, and Richard Zhu. “Yinglan Tan: Scaling a Venture Capital Firm in Southeast Asia.” Harvard Business School Case 823-025, July 2022, page 8-9.

Phil eventually joined the company as co-founder and CEO, where he became instrumental in working with Budi to expand Shipper’s O2O logistics capabilities with a stronger warehousing value proposition, offerings for enterprise businesses, among other improvements. Importantly, the company began attracting capital on top of this momentum with successive rounds in the next three years, and now has raised more than US$100 million up to Series B.

In taking Shipper to the next level, the company leadership also leveraged the support of its investors, including Insignia. The venture capital firm provided early support in speeding up product development through its in-house engineering team, and later on also shared strategic advice when it came to thinking about how to develop expertise and experience in the company’s organization as it scaled.

From matchmaking Phil and Budi to supplementing tech capabilities early on and then providing broader organizational development insight, there are many layers to how venture capital firms are able to help on the people side of the company building equation, where arguably the multiplier effects are greater than any other type of value add.

In addition to the variety, the common thread across all these types of support is it revolves around the venture capital firm’s ability to attract the right talent with the right experiences and skillsets (i.e., entrepreneurs looking for their next venture, engineerirng talent, operator insight, etc.), hammering home the idea that a venture capital firm is not simply as an investment company, but a platform for such talent and ideas.

“VC Value-Add” Doesn’t Exist in a Vacuum

Across these examples of how a venture-backed startup leveraged venture capital beyond follow-on investments, there are three key takeaways:

- Value-add doesn’t end with the value-add itself. In B2B business, customer success is an important function, ensuring services provided are indeed helping the customer to strengthen retention and loyalty, and the same applied to portfolio management. It’s not just about individual tidbits of help but how these all tie together and lead to the company achieving its north star metrics and mission.

- Both cases involved companies that were invested in quite early and therefore the kind of support provided was tailored to that stage of growth. As portfolio companies grow and evolve, there is the question of how the portfolio management capabilities of the firm need to or should evolve as well. Of course, some investors take a step back and others build up growth-stage capabilities, and this is dependent on the scope, focus, and patience of the investment firm. If anything, the two examples in the case illustrate just how difficult it can be to scale this kind of involvement and support while still keeping things lean and efficient, considering just how many more such companies a VC has to invest in and support to find and grow fund returners.

- Value-add are just as much about what the company has built as it is what the investor can bring to the table. It is a multiplication of existing resources rather than addition of outside help. Super’s pivot made sense not just because of market research on the part of the VC but also because of what Nusantara Technology had shored up in terms of on-the-ground market insights and resources in the industry (e.g., supplier connections, agent network building experience, cash, etc.). Phil’s contributions to Shipper would not have been as needle-moving if not for the work Budi had already done in terms of shaping up Shipper towards a position where it could take off even further.

Ultimately, investor value-add doesn’t exist in a vacuum. It involves long-term maintenance, evolution on the part of the investor to match the changing needs of the company, and being able to work with a good company in the first place (to become great).

Learn more about how you can dive into the world of venture capital in Southeast Asia — not just the investing but also portfolio management side — on Insignia Ventures Academy.

Paulo Joquiño is a writer and content producer for tech companies, and co-author of the book Navigating ASEANnovation. He is currently Editor of Insignia Business Review, the official publication of Insignia Ventures Partners, and senior content strategist for the venture capital firm, where he started right after graduation. As a university student, he took up multiple work opportunities in content and marketing for startups in Asia. These included interning as an associate at G3 Partners, a Seoul-based marketing agency for tech startups, running tech community engagements at coworking space and business community, ASPACE Philippines, and interning at workspace marketplace FlySpaces. He graduated with a BS Management Engineering at Ateneo de Manila University in 2019.