This article was co-authored with Kingsen Yan, an edtech founder and now an investor working with us at Insignia investing in the next big edtechs in Indonesia. Reach out to him at kingsen@insignia.vc.

- Rise of MOOCs (massive open online courses) in Indonesia boosted by Prakerja — but is it sustainable?

- Delayed school openings across the region incentivize adoption of LMS

- Growth of edtech also puts spotlight on internet connectivity issues in the region

- Formal education edtechs race to capture learning cycle of students — key acquisitions within this decade

- Informal education platforms have to up their certification/employability game

- Edtechs with freemium model have to overcome conversion challenges

- Venture Capital POV: COVID19 is a crucial filter for edtechs in Southeast Asia

In Southeast Asia, education has traditionally not been as appetizing for venture capital compared to other consumer services like fintech or ecommerce due to a number of factors that limit the ability of a tech startup in the space to achieve both scale and profitability — niche cultural behaviors and content needs across markets (i.e. different languages of instruction, curricula), infrastructure issues (e.g. internet connectivity), and lack of regulatory incentives, to name a few.

And while edtech has a couple of things going for it as well like rising middle-class incomes, a large portion of which is spent on education and supplementary classes, the pandemic really put the pedal to the metal in driving adoption of edtech platforms across the board.

Broadly, edtech can be categorized into those integrating or supplementing formal education (eg test-prep, online instruction, learning management systems) and those focusing on learning outside of formal education (eg MOOCs, language learning, certificate courses). Our portfolio companies Pahamify, Tenopy, and Edmicro are in the former, and platforms like Udemy, Coursera, or Duolingo are in the latter.

Both categories got a boost in Southeast Asia, as students and schools shifted their interactions online, and as more people looked to be productive online. In the same way that public investors became interested in platforms like Zoom because of increased demand for video conferencing tools, edtechs also began attracting more VCs, especially those serving the formal education system, with this increased revenue potential.

Incentives and endorsements from governments in the region to use these platforms also “subsidized” what would have been marketing costs for these platforms, creating a short-term relief for the business model of edtechs.

This interest may not have all translated into concrete deals, but at the very least those already invested in these edtech platforms before the pandemic doubled down on their investments or brought in co-investors in an effort to place their stake alongside competitors.

But that was 2020. Now in 2021, the question is whether this growth will continue and will more deals arise in the space in Southeast Asia. The short answer? Whether more VCs will be converted and put money where their sights are set will depend on how the edtech firms will handle (i.e. retain and monetize) their newfound growth.

We’ve been asked this question quite a few times by journalists, along with our thoughts on some developments in the edtech space especially in Indonesia, so we’ve decided compile what we’re finding interesting as venture capitalists in the region’s edtech space at the onset of 2021.

Rise of MOOCs in Indonesia

Last year, the Indonesian government launched a program called Prakerja, giving incentives for the unemployed through Pre-Employment Work Cards so that they are able to upskill or reskill themselves through online courses from platform partners such as Skill Academy, etc. After the participants take a course on the partner platforms, they are eligible to receive IDR 2.4 million (roughly USD180) in cash to their bank accounts (arguably what the participants are most excited about). Over 2020, Prakerja achieved its target of 5-6 million participants, and has planned on continuing the program into 2021 with about 10-20 trillion IDR budgeted, although previous participants can no longer join.

Based on the initial online response on the program, it seems that there’s a lot to be said about how effective the program is in terms of converting the upskilled users into employees. If participants come onto the platform without finding a clear value proposition, they’re more than likely to fall through the cracks of the conversion funnel, and this won’t be sustainable for the business.

At the same time, however, Kartu Prakerja also brought MOOCs into the spotlight, which haven’t been taken seriously because of the quality of the content and the language barrier preventing Indonesians from widely adopting global MOOCs like Udemy. Some non-edtech platforms like Tokopedia and Bukalapak even started investing in their own partnership with Prakerja. Participating platforms have also been fuelled up, not just in terms of users, but also revenue from the program’s rebates (up to 15% by regulation for every transaction from Prakerja). So even though 90% of their revenue comes from Prakerja, there’s an opportunity for these platforms to leverage the cash to focus on independent monetization strategies and retention.

Given that the Kartu Prakerja program is continuing into 2021, it is still not yet clear what Indonesian MOOCs will do to retain users, independently monetize or further concretize their value proposition (i.e. prove its efficacy or the employability of users). MOOCs that are able to do so may attract regional VC backing, and perhaps that may be a narrative worth following this year.

From a consumer perspective, the Prakerja could potentially also impact the culture of learning through online content and result in more widespread acceptance of these platforms, not just by jobseekers, but also employers.

An important element in all of this moving forward will be the ability of MOOCs to bridge their content to certification and concretely drive employment through their course offerings. Focusing simply on incentivizing training is just one part of the equation, and perhaps the government can also step in with the employment aspect and also incentivize businesses to employ participants of the Prakerja program. The challenge here is that most companies will more likely make more conservative hiring options these days.

“Kartu Prakerja also brought MOOCs into the spotlight, which haven’t been taken seriously because of the quality of the content and the language barrier preventing Indonesians from widely adopting global MOOCs like Udemy.”

Delayed school opening in Indonesia incentivizes adoption of LMS

Schools in Indonesia were supposed to reopen this month, but because COVID-19 cases reached all-time high, school openings have been delayed again. Because of this, we’re expecting that both public and private schools will (continue to) adopt school management systems to keep instruction delivery and feedback with students going smoothly online.

The government has also been very supportive in making the disbursement process of public schools easier so they can subscribe or buy services from third-party providers, especially edtech. The only question remains is whether all of this trend is going to be sustainable and change the culture of how education works in Indonesia after COVID-19 is no longer a threat.

Driving adoption of edtech in Southeast Asia pushes the need to strengthen internet infrastructure

Several edtechs have been exploring live online instruction (one-to-many format) amidst the lockdowns, but in many areas across the region, this exploration has been met with several challenges, foremost of which is internet connectivity. While not a new problem, the fact that it remains a challenge for many edtechs to effectively implement services like live online instruction at scale means there’s still a lot to be done in improving connectivity, especially across archipelagos like the Philippines and Indonesia.

The race to a unified platform for formal education edtechs

Moving into 2021, “formal education” edtechs will be capturing more of the students’ learning cycle to create what we call a “unified edtech platform.” Test preparation has been low-hanging fruit for edtechs, especially in a region where national/school entrance exams involve a lot of investment (monetization opportunity) and are very much focal points in student life (clear need).

Now we’re seeing edtechs that have cracked the test prep use case move on to other aspects of the students’ learning journey. Obviously, lockdowns and resulting government incentives/promotions have forced students and schools to use more edtech platforms, but the sustainable approach is for edtechs to develop use cases according to what their user base needs.

The interesting thing about creating this “unified edtech platform” is that edtechs can start at any point in the cycle and expand from there, so there are many permutations of edtech players that would be worth looking at purely from a go-to-market perspective. Edtech players that capture most of this cycle and amass enough capital from the process would also be in a good position to acquire smaller players, and reaching this “consolidation” stage in the landscape would be a significant milestone in this decade.

With this race to build a unified platform, we can expect growth and spending in “formal education” edtechs. Governments are also likely to continue promoting and incentivizing the usage of these platforms as they try to upgrade their educational systems. These edtechs also have a higher likelihood of achieving profitability because of recurring usage embedded in their value proposition, almost similar to a SaaS / B2B model, especially if they sell directly to or distribute through schools. The ceiling for growth may be lower than “extracurricular education” edtechs (limited by demographic), but once retention is achieved, long-term returns are more stable.

“Edtech players that capture most of this cycle and amass enough capital from the process would also be in a good position to acquire smaller players, and reaching this “consolidation” stage in the landscape would be a significant milestone in this decade.”

Informal education platforms have to up their certification/employability game

On the other hand, extracurricular or informal education edtechs are also driven by more factors than formal education edtechs, depending on the kind of content and certification they offer. For example, certificate courses will likely continue to increase in demand with massive offsets in the job market resulting in many people looking for a new job or career opportunities. Language learning on the other hand will be dependent on the disposable income of the target market, and the incentives to learn a new language — in the way that for example, non-English speaking countries incentivize spending for English learning courses with the higher employability of TOEIC passers.

Sustainable growth depends on what the motivation is for the students to use these skill-specific platforms. It’s a qualitative variable, but the best edtech companies are able to engage with their users in a way that gives them insight into the mindset of their target students.

Coming from the massive adoption influx, it will be important for these edtech platforms to be sensitive to where their users are coming from and build retention with them, either by diversifying the selection of content to meet their needs or introducing adjacent services that create an experience these users can’t find anywhere else.

Skill-based platforms and school-focused platforms also provide very different value propositions. Whereas adoption of school-focused platforms will tend to be constrained by time period (eg students are students only for a certain of time) and population (eg only a certain number of schools/students in a market) — skill-based platforms can attract users with a longer lifetime or users can return anytime and there are more opportunity network effects.

The catch is that skill-based platforms need to crack the market in terms of what skills are worth teaching (i.e. will it improve employability?) and who will be there to take these classes — both of which are easier to figure out from a school-focused platform’s perspective. Sustainable growth for the skill-based platforms then means evolving the business by continually asking these questions as it aims to cater to more users, and it is possible as we’ve seen with the likes of Udemy or Coursera.

“The catch is that skill-based platforms need to crack the market in terms of what skills are worth teaching (i.e. will it improve employability?) and who will be there to take these classes — both of which are easier to figure out from a school-focused platform’s perspective.”

Overcoming the conversion challenge of the freemium model

Edtechs will also be focusing more on monetization or value extraction to ensure they can sustainably grow and continue providing their services. This will be a challenge especially for edtechs that adopted a freemium model (or perhaps even shifted to one) over the past year.

Usually, when the conversion from free to paid users doesn’t pan out, there are usually two reasons. Either the platform has been attracting the wrong users — this happens when the business’s marketing or go-to-market strategy is misaligned with the product’s value proposition — or the user experience just isn’t valuable enough to the user to warrant paying for the product. And the value proposition itself has to significantly evolve for users converting from free to paid. If this difference between user experience from free to paid isn’t clear or valuable enough, then it will be difficult to convert.

Depending on the educational content, convincing users the switch is worth it is inherently difficult because of the free competition in the market and how replaceable the source of the content can be for most subject matter (imagine a language learning platform competing with Youtube videos). And even if the leverage to convert is clearly valuable from the learning perspective (for example, one-on-one with experts or unlimited practice exercises/content or data analytics), it is possible that it may simply not be valuable enough to cover the entire user base, because learning does require effort on the part of the user and the users may not simply be invested enough in learning the subject matter, or the subject matter itself may be quite difficult to master/ the rewards are too incremental (e.g. chess).

Another way to look at it is to simply work on expanding the reach of the platform so that 3% becomes a slightly more significant number in real terms. For example, instead of working on getting the conversion from 3% to 6%, the platform could work on expanding its reach from 100K to 1M, raising the paying users 10x vs 2x. Another strategy is to expand across types of subject matter, especially for informal education platforms (e.g. Udemy or Coursera with multiple subjects), which creates an additive effect, 3% from a data science course plus 3% from a Bahasa Indonesia course, and so on and so forth.

This conversion challenge is inherent to the freemium model, and while it may be significantly tougher in edtech, considering the free competition and variable propensity for users to learn the particular subject matter the edtech is focused on, there are also many ways to work around low conversion rates.

Apart from thinking of the other strategies mentioned in (7), one crucial thing we’ve noticed from our edtech portfolio companies is their ability to listen to their users, whether through user behavior data or plain-old customer conversations, which many tend to underestimate. Pahamify regularly converses with their users on Twitter for example, where they get ideas on how to improve their platform and assess what other services to provide in the future. Our Vietnam edtech portfolio Edmicro made it a point to visit the schools that use their platform to get direct feedback from the teachers and principals. Platforms that don’t have this direct line to their customers and are more passive in their feedback loops are more likely to struggle in booking paid users and retaining them.

“Depending on the educational content, convincing users the switch is worth it is inherently difficult because of the free competition in the market and how replaceable the source of the content can be for most subject matter.”

VC POV: COVID19 is a filter for edtech startups

Instead of looking at the accelerated adoption of edtech platforms as a signal that edtechs are the “next big thing,” VCs see this pandemic-induced growth as a critical filter that winners will rise above.

One thing we’ve seen over the pandemic is that opportunity does not equate to growth. A spike in adoption or users is not necessarily all good for a digital platform — as we write in our book Navigating ASEANnovation, “One challenge for platforms experiencing sudden spikes in demand is being able to keep up both on the technology side and the operations and customer experience side.” The pandemic for edtechs essentially creates an organic experiment for these platforms, whether their tech and operations are fit to handle or adjust to massive influx of users.

And when it comes to edtech, it’s all about the product. As Pahamify co-founder Rousyan Fikri said in Navigating ASEANnovation, “The thing in edtech is students just want to use the best product. Product that is reliable, has a good UX and offers good content.” Those with the most durable products will likely gain the lion’s share of the funding moving forward.

Then from a business model perspective, this pandemic-induced rally will also test the retention and monetization strategies of edtechs. These edtechs had value propositions even before COVID, and while users that were onboarded on the platform amidst the pandemic will likely have the pandemic as their initial motivation for adoption, the best edtechs will be able to engage these new users in a way that brings them to the core value proposition — an invaluable supplement to classroom instruction, for example.

In the case of our Indonesian edtech portfolio Pahamify, as we write in CEO Dr Mohammad Ikhsan’s contribution to Insignia Business Review, their paid customers grew around 50x over the first half of 2020. In our podcast with co-founder Rousyan Fikri, he says that they continued to trend frequently on Google Play Store and even increase their app store ratings even as their users multiplied.

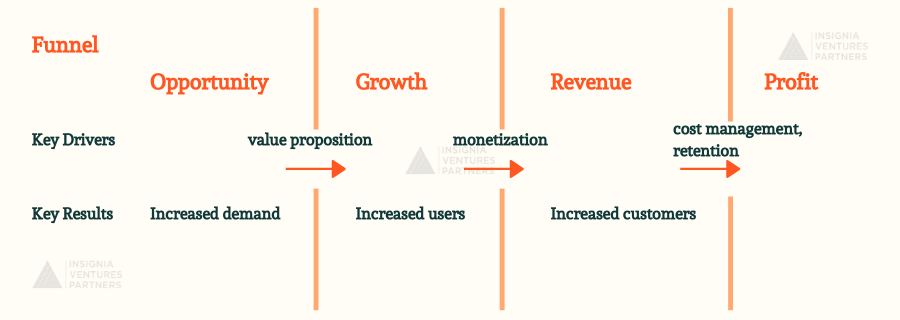

As we’ve mentioned, opportunity does not automatically result in growth. And the corollaries to that are, growth does not automatically result in revenue, and revenue does not automatically result in profit. The impact of growth on revenue and profit is only realized when the business has key drivers in place (monetization, retention, cost management) to convert growth into revenue and profit. Edtechs that have already clarity on these things — for example, Pahamify was already product-driven and spent little on marketing even before the pandemic — are more likely to translate massive growth into capital for further organic growth.

“The pandemic for edtechs essentially creates an organic experiment for these platforms, whether their tech and operations are fit to handle or adjust to massive influx of users.”

Kingsen is a former founder and venture capitalist with a passion for education technology. In 2017, he co-founded Eddemy, a B2B data analytics company for school management through surveys, and he led the company to achieving 1.2 million surveys annually before it closed amidst the pandemic in 2020. He then joined Insignia Ventures Partners as an Investment Analyst for the edtech sector, and he also began contributing insights into edtech on Insignia Business Review. He is currently working on his next venture. Reach out to him on Linkedin.