Much has been said about the pandemic and the ensuing measures to contain it accelerating digitalisation across the board. Combined with Southeast Asia’s increasing internet penetration, it seems like a done deal, but there’s more to this story. Previously, we covered the complexities of digitalisation from the business point-of-view. In this essay, I look at it from a consumer perspective.

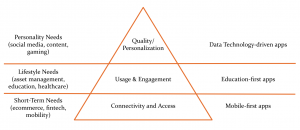

There are digital divides that prevent the region’s growing population of digital consumers from maximizing the value they get from products and services on the internet. This can range from the basic lack of access to the internet and devices, to the noise that prevents creators and audiences from finding each other (or in many cases, noise that leads to becoming misinformed). I’ve broadly categorized these divides into three levels and tackle how the app experience is changing to close these divides for consumers:

- Connectivity: Mobile-first approach offers asset-light connectivity and access.

- Usage: Education-first applications sustain gains on usage and engagement.

- Quality: Data technology links digital consumers to more personalized interactions amidst the noise.

Mobile-first approach offers asset-light connectivity and access.

The disparity is none starker than in Southeast Asia, where six countries in the region rank in the top 10 globally for mobile internet usage while only three countries in the region have over 80% internet penetration (Singapore, Brunei, and Malaysia). And though this penetration is expected to increase and multiple 5G network launches in the region are projected over the next five years (albeit slowed down by the pandemic), high-speed internet remains out of reach for many in terms of infrastructure and cost.

This disparity is not a new problem, but it has become a pressing issue with lockdowns and social distancing forcing areas that have not had stable internet access to all of a sudden transition to online tools. The results of this sudden shift are in education, where some schools do not have the tools or the capabilities to even test distanced learning. This disparity also manifests in the informal and paycheck-to-paycheck sectors, where jobs have been lost or put on hold due to lockdowns and now these workers have to look for new ways to generate income. In Indonesia, half a million people in Indonesia’s informal sector have been put out of work. This contrasts with the tech-enabled workforce who actually have the potential to drive network effects for internet adoption, especially those who came home from the region’s megacities to their hometowns.

Because of these issues, it has been an inherent challenge in Southeast Asia’s tech startup ecosystem to build mobile-first platforms. While the more effective solution to narrow the connectivity divide certainly involves more widespread and institutional measures, building for mobile has proven effective to close the gap. The mobile-first platforms do not only reduce the cost of being able to access these apps but also force apps to be more “asset-light.”

For example, since 2016, Payfazz has been building a financial services ecosystem for the smartphone to make these services accessible to rural Indonesia. They started out with basic needs like bills payments have since expanded into other services like loans and store management applications. Regardless of the service, it is all united by the mobile-first approach. Founders of Vietnamese edtech Edmicro stressed the importance of this mobile-first approach for online education apps especially for communities that do not have access to desktops and PCs.

Education-first applications sustain gains on usage and engagement.

But setting up internet infrastructure and making sure applications are more accessible on mobile won’t directly translate into online activity. According to the 2019 GSMA mobile internet connectivity report, “greater connectivity does not always immediately follow coverage.” In the same report, the East Asia and Pacific region has a 4% connectivity gap (vs 30% in Sub-Saharan Africa) but a 41% usage gap (vs 46% in Sub-Saharan Africa). There are often understated barriers to usage like literacy and affordability, that make

But then the onset of COVID19 is forcing the usage gap in Southeast Asia to close from two directions. There are digital migrants who are beginning to use apps that have already been around for a while (e.g. students using Google Drive for the first time for schoolwork). Then there are new apps or apps that are introducing new features to engage users in new activities. 85% of digital consumers in Southeast Asia tried out new apps in 2020, majority of which were social media and video streaming apps (i.e. content-driven, as opposed to transaction-driven).

With this boom in digital consumption, apps are also evolving to meet these new users and deliver on experiences that will retain them. To that end, customer journeys are being built around by lifestyles rather than transactions. An ecommerce app is more than a platform for buying and selling. There’s a saving element with point systems and games, and there’s an entertainment element with live shows and events. All of these combined create an ecosystem for the online shopper’s lifestyle.

As digitalisation takes on more personalized and nuanced applications, from healthcare to education and asset management, building for the lifestyle rather than the transaction will be the norm. Foundational to transitioning this influx of digital consumers in Southeast Asia is an “educate-first” approach (vs pay-first, educate-later) where content and community is a key part of the product and user experience, even if the app is not necessarily a native content or community platform.

Ajaib’s investment platform was developed for first-time investors to become successful investors. It’s a process that takes time, but they don’t waste any of it with their record-speed onboarding process, low starting cost to invest, and their financial advisers available on WhatsApp. Edtech Pahamify prides itself on their strong customer relationships they build with the high school students that use their platform. This manifests through their responsiveness to feedback on platforms like Twitter and availability of career consultants on their platform.

Data technology links digital consumers to more personalized interactions amidst the noise.

With more apps, more content, and more communities online, the saturation will drive users to search for quality amidst the noise. In Southeast Asia, the internet can only be expected to become noisier with more activity online. Incidentally, this concentration of activity also fuels data technology (DT). DT will be powerful for digital consumers to close the quality divide, as it engineers more curated online experiences, brings creators closer to the right audience, and can link online activities to offline decisions.

In China, DT took over the internet with the likes of Baidu and Bytedance linking users to information and services on top of content consumption. DT is still emerging in Southeast Asia, as tech companies cash in on data to develop the internet experience of the region’s growing online population. Content platforms like Waves enable audio-first or audio-only creators in the region to better engage their audiences. Esports platforms like EVOS created its own entertainment arm for their talents to interact with their fans. Live streaming platforms like TikTok are catering to online shopper lifestyles by experimenting with added features so that their in-app content can connect users to products (ecommerce) or even health information.

***

These gaps in access to connectivity, usage, and quality show how segmented the internet experience is for digital consumers in different demographics and geographies across Southeast Asia. Compared to people living in rural areas, people living in megacities like in Singapore or Kuala Lumpur will not only have faster internet speed (connectivity) but will also be more digitally literate (usage) and be better positioned to find better content and information for their needs (quality). As digitalisation continues to fly over the region, it will not land in the same way everywhere, so the planes need to be suited to the environment they are landing on.

In summary

Paulo Joquiño is a writer and content producer for tech companies, and co-author of the book Navigating ASEANnovation. He is currently Editor of Insignia Business Review, the official publication of Insignia Ventures Partners, and senior content strategist for the venture capital firm, where he started right after graduation. As a university student, he took up multiple work opportunities in content and marketing for startups in Asia. These included interning as an associate at G3 Partners, a Seoul-based marketing agency for tech startups, running tech community engagements at coworking space and business community, ASPACE Philippines, and interning at workspace marketplace FlySpaces. He graduated with a BS Management Engineering at Ateneo de Manila University in 2019.