This piece features insights from a panel discussion with our senior analyst and Indonesian agritech expert Andri Lau, alongside Banoo Indonesia CEO Azellia Alma Shafira, Sunway iLabs Ventures Head Eleanor Choong, Artem Ventures’ SaiKit Ng, and “Hungry for Disruption” author Shen Ming Lee.

***

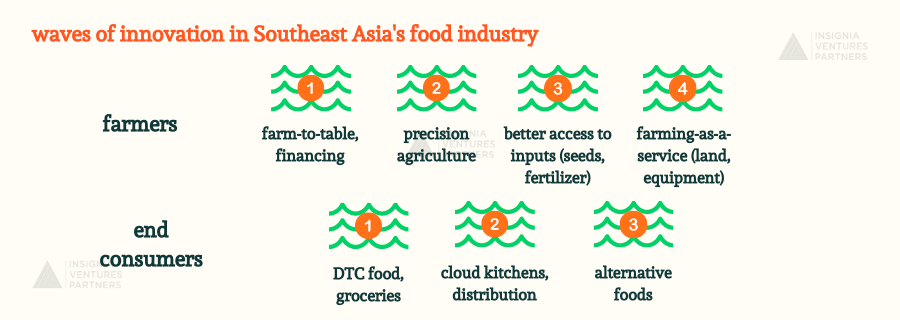

When it comes to innovating Southeast Asia’s food system, as it is with any two-sided market, you can approach it from a supply point-of-view (i.e. farmers or agriculture) or demand point-of-view (i.e. consumers).

From either vantage point, Southeast Asia’s still has a long way to go in terms of radically improving the status quo — how much farmers earn, what kind of food is available to consumers, etc. Just as we’ve written about there being waves of innovation in Southeast Asia’s startups ecosystem, there are also waves of innovation when it comes to the region’s food system that venture capitalists especially can use as a framework to understand where this improvement and innovation is headed in the future.

And even if food delivery has boomed in Southeast Asia with the likes of Grab, Gojek, Deliveroo, and FoodPanda, it’s just a small subsection of the region’s entire food system, which begins with production in farms or labs (in the case of alternative meats, for example), goes through a fragmented supply chain of distributors and retailers, before finally ending up in marts or restaurants where delivery riders many consumers are familiar with come to pick up orders. This means that the business models of food delivery, two-sided platforms may not necessarily apply to all the waves of innovation we describe below.

Empowering farmers

For tech startups approaching the issues of Southeast Asia’s food system from the farmer point-of-view, the goal is to optimize the process and infrastructure of farming then scale it to become more accessible and lucrative for non-farmers to even consider participating in the industry.

Concretely, this means radically improving the average income of the farming profession in the region, which is currently at around 100 to 200 dollars per month. Considering how much value there is in what farmers do for economies in Southeast Asia (agriculture being a large chunk of GDP), the gains of improving farmer income could be exponential.

But given where the farming industry is right now, asset-heavy, sophisticated solutions are not necessarily the most practical and scalable go-to-market. With the current income of farmers, and even with existing co-ops, they likely don’t have enough buying power to purchase technology or equipment to increase productivity.

This means the waves of innovation for farmers is a progression from increasing buying power to enabling sort of a “farming 2.0” (i.e. better means of production) then scaling the reach of this “farming 2.0” to a wider population. In Southeast Asia, even though there are businesses that fall into the first three waves, we are in the middle of the first wave right now in terms of widespread adoption and investments, while the second or third wave is maturing in markets like India or China.

First Wave: Taking out distribution inefficiencies with farm-to-table distribution

The first wave is the marketplace model, where you have a platform that optimizes farm-to-consumer supply chain distribution primarily to reduce post-harvest losses of farmers. This in turn increases income for the farmers over time as costs are offset by more efficient sales of their produce.

One of our portfolio companies Sayurbox has been focusing precisely on this wave of innovation:

Second Wave: Increasing productivity with precision agriculture

The second wave goes more into precision agriculture where you have companies developing technologies to help farmers save costs directly from better farming techniques. Apart from reducing costs, precision agriculture also is meant to increase yield, and with distribution inefficiencies already out of the equation, the benefits of increasing yield are much more meaningful.

Third Wave: Expanding agricultural toolkit with better access to inputs

The third wave is all about helping farmers gain better access to inputs, including seeds, fertilizers, so on and so forth. There are companies like DeHaat in Indonesia or Farmers Business Network in the US that connect farmers to suppliers via marketplace offering full-stack agricultural products and services.

Fourth Wave: Scaling benefits with farming-as-a-service

If the first three waves are all focused on making the work of an individual farmer as cost-effective and productive as possible, the fourth wave is all about making it easier for farmers at scale. With better access to input, farmers can then gather as a community and have better tools/equipment, data transparency on market, and better economics of scale (i.e. able to produce high-value commodities). With the farming-as-a-service model, farmers can share land and equipment in a scalable way. They can get access to machinery even if they only own less than one-hectare if it can be used by multiple farms. Apart from supporting farmers, farming-as-a-service could be a way to get more individuals into the business of farming, perhaps even in urban settings through vertical farming.

Empowering consumers

When it comes to food innovation from the consumer side, it’s similar to the waves of innovation from the farmer perspective in that solving for distribution and supply chain efficiency is a huge part of it, but the end-goals are different. The aim is for consumers to be able to have accessibility to healthier, more sustainable, and more affordable food options. Especially with the socio-economic problems exacerbated by COVID19, the way that food reaches consumers — and what kind of food reaches consumers — needs to be rethought.

And in Southeast Asia, just as it is with the waves of innovation for farmers and agriculture, even though there are businesses in the region working on all three waves of innovation, in terms of widespread adoption and investments, much of the focus is still on the first, though the speed at which this is changing is faster from the consumer-end than it is for farmers.

First wave: Better consumer experience with DTC

It’s all about solving supply chain issues and making the purchase and delivery of groceries easier. It’s not just about ensuring deliveries are made but even going further in terms of consumer experience — for example, enabling users to learn more about the freshness of the produce they purchase.

Second wave: Greater efficiency for brands and restaurants through cloud kitchens

The second wave is all about upstream distribution and product diversification. One example is the booming cloud kitchen model which enables brands and restaurants to meet the demands of consumers more efficiently.

Third-wave: Healthier, sustainable food options with alternative foods

Given the issues surrounding the sustainability and health of mainstream food production, alternative foods have become increasingly less “alternative.” With better DTC experiences and supply chain efficiencies, alternative foods can reach more consumers. We’ve previously written about what it would take to grow an alternative protein brand in Southeast Asia.

Overcoming external constraints

Whether looking through the lens of farmers or end-consumers, it’s clear that there’s still a long way to go for Southeast Asia in terms of riding out these waves of innovation. And just as it is with ecommerce, there are three significant constraints that need to be overcome to catalyze the adoption and development of agritech and food tech companies.

- Lack of talent: Agritech and food tech are not exactly hot spots for talent in the way that fintech or ecommerce are, and in order to bring in more professionals into the space there needs to be greater education in terms of how important the issues are in Southeast Asia’s food system, and how specific skill sets can help.

- Diverses priorities and approaches in terms of agriculture: While agriculture and food production are generally major contributors to economies in the region, the level of priority (and therefore funding) given to the sector by individual governments varies greatly. ASEAN may benefit from having a more unified or multilateral initiative supporting agritech and food tech ventures.

- Funding gaps: Funding in this space is slow, especially beyond the marketplace model, which means it is not necessarily an industry friendly to venture capital’s aim for rapidly scalable returns. This means there needs to be more private funding sources available for these ventures

***

The common thread running through all these waves of innovation we touched upon is the combination of “distribution” and “transparency.” With more efficient distribution of agricultural produce, food products, farming inputs and resources, combined with transparency on pricing, product grades, and consumer experience, it’s a win-win for farmers and consumers. Consumers will benefit from having more affordable, sustainable, and healthier food sources, while farmers see their livelihood improving with more productivity and more income.

Paulo Joquiño is a writer and content producer for tech companies, and co-author of the book Navigating ASEANnovation. He is currently Editor of Insignia Business Review, the official publication of Insignia Ventures Partners, and senior content strategist for the venture capital firm, where he started right after graduation. As a university student, he took up multiple work opportunities in content and marketing for startups in Asia. These included interning as an associate at G3 Partners, a Seoul-based marketing agency for tech startups, running tech community engagements at coworking space and business community, ASPACE Philippines, and interning at workspace marketplace FlySpaces. He graduated with a BS Management Engineering at Ateneo de Manila University in 2019.