Valuation adjustments opening up buying opportunities. Increasing demand to improve cash positions and pave paths to profitability. Pressure to shore up investment positions and drive exits for maturing funds. The rise of third-wave corporate innovation.

The stars are aligning for M&A to have its moment in Southeast Asia. M&A has always dominated the region’s exit landscape (thanks to the region’s inherent diversity and multiple markets with varying regulatory regimes), but the bear market makes it even more of a buyer’s market.

That said, a buyer’s market doesn’t necessarily mean a free-for-all. The bars are higher as they are for fundraising.

Over the years, we’ve had the opportunity to document and learn from some examples of M&As across our portfolio (scroll to the end of the article for a full list of related reads). From these, we’ve compiled learnings into a three-point checklist of considerations from the buyer’s perspective.

- Understand the purpose (growth, competition, synergy) and how it impacts your criteria for target companies (financial health, customer base/ market share, team, assets).

- Find out if you have the capabilities and bandwidth (beyond cash to spend) to actually even proceed with the transaction.

- Plan out how operations will look post-acquisition or post-merger (PMI). Is it still scalable?

- Consider how this will impact everyone involved in the transaction, from employees to board members and shareholders. What does buy-in look like? How will your network impact relationship-building and opportunities?

(1) Understand the purpose (growth, competition, synergy) and how it impacts your criteria for target companies (financial health, customer base/ market share, team, assets).

Growth-type transactions typically happen to build up competitive advantages in adjacent verticals or new markets, and these range from strategic acquisitions to tech deals for patents to acquihires (see CARRO acquisition of MyTukar, Ajaib acquisition of Primasia Sekuritas or Medici acquisition, Shipper acquisition of Pakde and Porter). More of these types of M&As are expected to happen for businesses where there is a large pool of smaller enablers and bigger platforms need to strengthen their retention channels and customer lifetime value with upsell capabilities (see this e-commerce enablers article on the blurring lines between marketplaces and enablers or this fintech article on M&As as a way to build banking stack).

Exhibit A: Saving time to win the market

Budi on Shipper’s acquisition of Pakde and Porter in 2020 (from a podcast): “We would trial warehousing beforehand ourselves. The challenge for that would be actually to have the know-how and also the tech stack that we need to run that operation. When we looked at Pakde, we were working together at the beginning when we helped them with the shipping. Then we realized that we could actually work together tighter to actually do fulfillment. We could see there are a lot of synergies there. And I think that’s how the conversations started. We actually met the Pakde founders through the introduction of people that we met on a plane. I think it was destined to be for us to work together.

And for Porter, we see that they had actually very strong shipping because they were building the same thing — building shipping networks and agent networks. Instead of us building the same thing — it’s a waste of time and resources, we thought, “Hey, we should just work together to build that agent network. So, we can save some time and win the market faster.” That was the whole idea around the acquisition.”

Competition-type transactions are more responsive with respect to the market, as in the case of buyouts of global companies’ regional operations by local competitors when they fail to make productive headway or have to roll back their expansion (the latter is more likely in this market).

Exhibit A: Hailing a ride to rollback expansion

From Backing the Bold, page 368: “Uber was on the receiving end of this twice as it expanded in Asia. First in 2016 when Didi acquired Uber’s China business as the latter was facing estimated losses of US$2 billion in a competition to gain market share. The second was only two years later in 2018 when Grab acquired Uber’s Southeast Asia business in exchange for a 27.5% stake in Grab at the time. Interestingly, this stake in Grab enabled Uber to also benefit from the Southeast Asia ride-hailing business’s SPAC merger. These transactions are often coined in the media as mergers but the transaction usually involves the homecourt or “winning” company acquiring the “losing” company’s business in the market in exchange for cash or a stake in the winning company. Here we use the word “winning” to connote the company that stays in the market and “losing” for the company that leaves. Once again, worth noting that even the “losing” company does not necessarily lose entering into these kinds of M&A transactions; it is likely more economical and beneficial financially down the line.”

Finally, synergy-type transactions happen when two adjacent players join forces to build an even bigger presence than they could achieve on their own, typically in response to competition or as a way to navigate the challenges of market expansion (see GoTo merger or Fazz acquisition of Xfers).

Exhibit A: The merger is the moat

From article on GoTo merger: “The merger IS the moat. GoTo is a strategic response to the rising competition in Indonesia posed by the likes of Grab and Sea, not just in e-commerce but financial services as well. The merger does not only create space in the market for these two players but potentially opens up new avenues for growth that were previously impractical or impossible. For example, there’s the often-mentioned flywheel for funneling a greater selection of services and merchants on their platforms through the aggregated data obtained through existing services. The successful merger is not additive but multiplicative or even exponential in its returns. So while the merger is in itself a consolidation of two unicorns, it also has created a moat for the tech group to hold off the consolidative advances of competitors in the country.”

Exhibit B: License to expand efficiently

Fazz Deputy CEO Tianwei Liu on Payfazz and Xfers coming together (from podcast): “Hendra and I were saying that we are both trying to expand the business. I’m looking to go into Indonesia; they were expanding out. But a problem is gonna happen where if you’re not local enough, we don’t have enough presence, and acquiring licenses is extremely difficult to navigate.

So we saw a lot of synergies already with the fact that our businesses have so much overlap and we need each other to expand a lot. So that became one of the key drivers for why we decided to come together as a company. Because together we can achieve a lot more and licenses will allow us to basically have a [wider] reach and give more services to our existing clients.”

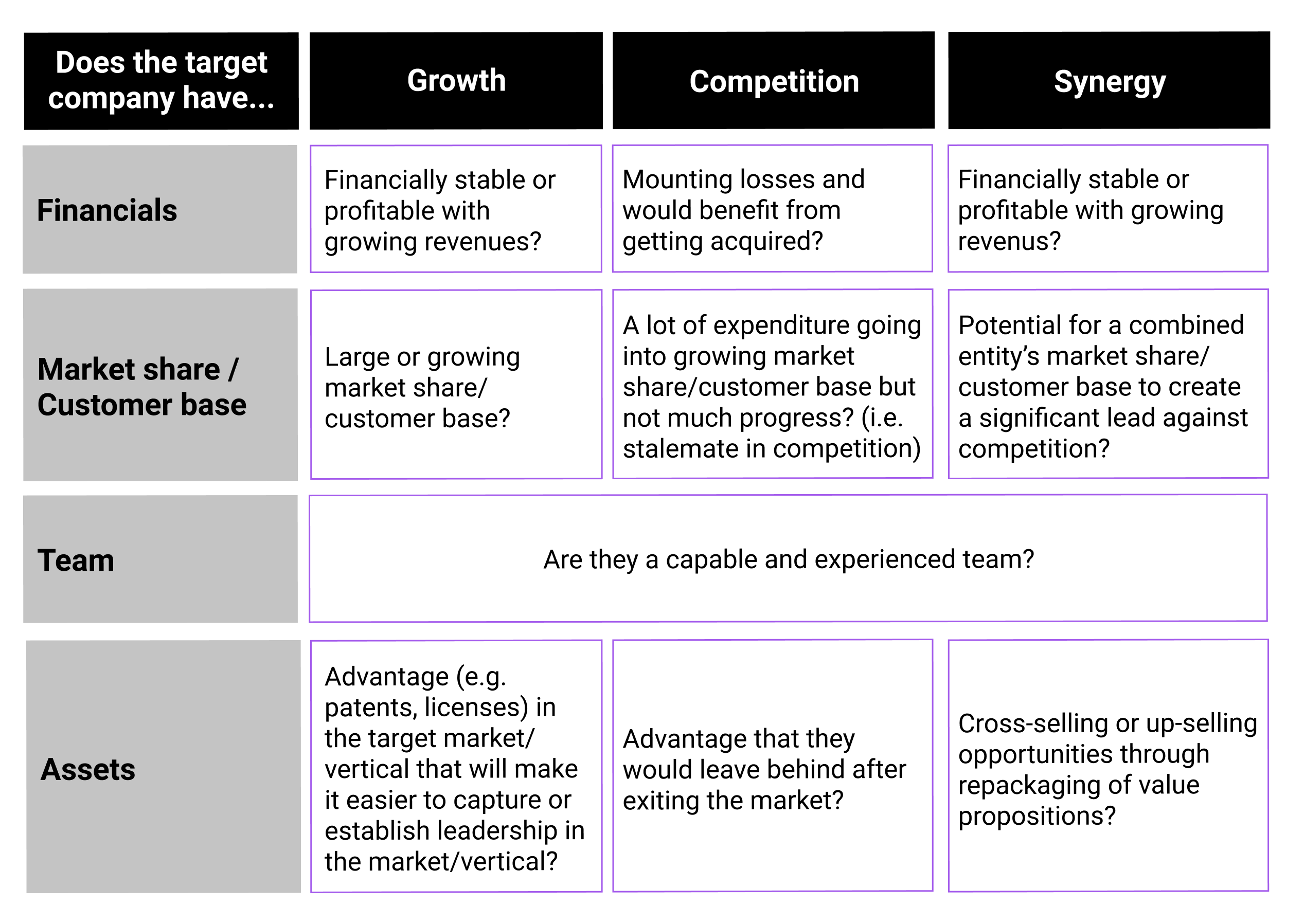

The reason behind thinking about the “why” is it helps to filter through the criteria for the ideal target company, as this table from Backing the Bold page 372 illustrates:

(2) Find out if you have the capabilities and bandwidth to actually even proceed with the transaction.

This goes from sourcing targets to running due diligence (potentially engaging with third parties) to the cash and people needed to see the process through to the end.

Chih Cheung, Founding Partner of SEA Logistics Partners and Managing Partner of family office C2 Capital Limited, brings this consideration up in a discussion on consolidation amidst the pandemic in a 2020 podcast: “I think in general, in a time like this, the company that actually has a strong business model, a strong management team, and a strong capital base, they’re going to have incredible opportunities to buy things for cheap. And so in some way, there’s going to be consolidation.”

Another consideration with regard to capabilities is how this measures up against the wider world of potential buyers and what their activities look like. For the longest time, this has been dominated by… ”companies in more mature markets that have been looking to Southeast Asia to expand, a case in point being Alibaba. Though in this regard, many big tech companies from mature markets have largely exercised restraint and have only confined themselves to making significant private investments. (Backing the Bold page 364)”

But more recently, this widening world of buyers in Southeast Asia has come to include the emergence of third-wave corporate innovation, which is described in Backing the Bold pages 20-21 as follows: “The first wave of corporate innovation saw corporates dipping their feet into the startup pool through low-commitment partnerships. Then the second wave features corporates setting up investment vehicles to have a more direct and strategic influence on the way startups are able to bring value to corporate strategy.

The third, new wave is all about startups themselves scaling up to become these massive technology groups and also setting up their own CVC funds to invest in the next generation of startups. Third-wave corporation innovation through these unicorn CVCs brings in the best of both worlds: the size and scale of a corporation with the understanding and experience of what it takes to grow a startup. The foremost example is Sea Group’s US$1 billion venture fund.”

(3) Plan out how operations looks post-acquisition or post-merger. Specifically, it’s important to ask, how will the transaction impact scalability? In the line of business you are in, does consolidation benefit scale?

Chih Cheung continues from the same podcast: “And I think certainly in industries where consolidation does benefit, you’re going to see more of that so scale benefits certain types of industry, for example, you kind of mentioned hotel, right. I think having a bigger scale makes you run more efficiently. Having said that, given what’s going on in the supply chain, I’m not sure having a bigger scale really helps. For example, if all your factories are in China, it’s not good for you to buy more factories in China, because your customers actually want to diversify sourcing things. So it really depends.”

Budi shared his thoughts on consolidation and M&A in the logistics space in this 2021 podcast: “I think broadly M&A will happen for the whole logistics space, because there’s a lot of things to do. And when we have a lot of logistics companies, it’s hard for them to do M&A mainly because there’s no technology integration. So everybody has their own software. They have their own piece and they might not even have software, but as we grow our tech stack, we can see that there’s potential like this type of M&A will happen again, but in particular, we don’t have anything specific. We don’t have any target, like, “Hey, we should go and buy this, or we’re going to acquire this company.” We look at the opportunity. We look at what comes and we will decide accordingly, and we’ll see how each entity can add value to our company in the long run.”

(4) Consider how this will impact everyone involved in the transaction, from employees to board members and shareholders. What will it take to get buy-in?

There’s also the nature of these transactions that take some time and is often built on years of relationship building even prior to considering the transaction itself, as Backing the Bold pages 396-397 cover: “This execution is not always about hard-selling the portfolio company or getting right into the M&A and IPO process. Oftentimes these relationships are built over months or even years, early on in the life of the company, so the decision-makers in these exit targets already become familiar with the portfolio company when the time comes to act. It is also worth noting that the DPI Hit List also intersects heavily with the fundraising value-add of VC firms. That means the strategic investors the firm can bring in an earlier round could potentially be acquirers down the line.”

What this M&A journey will look like often depends on what the network of the company and leadership looks like (though often underestimated), as Backing the Bold page 149 covers: “But there are other ways to acquire customers and scale the business more strategically than burning cash — in Southeast Asia, that could mean leveraging a strong distribution network (i.e. referrals, FOMO, integrating it into regular interactions, B2B2C), capturing as much of the life cycle of a customer as possible through adjacencies, and tapping into network effects of local partners through investments or M&A. And venture capitalists can have a significant influence in supporting a startup’s search for this balance of scale and profitability.”

And speaking of venture capitalists, it’s also worth considering how investors/shareholders will be impacted (both positive and negative) by a potential transaction. Backing the Bold page 382 covers the exit perspective of a potential M&A vis-a-vis IPO: “…there have not been that many other exit options in the region unless the company reaches a certain size that could have only been achieved by either becoming a Southeast Asia dominating unicorn or Indonesia- dominating unicorn, so unless these two scenarios are possible within the fund’s lifetime, selling to acquirers is likely the top option for an exit strategy. This is also complicated by the lengthier exit timelines (i.e., longer it takes for a company to reach a valuable enough exit valuation), as well as the historical lack of infrastructure and liquidity to support local IPOs, though the latter has been changing as well with the likes of IDX adjusting to host its local tech unicorns.”

Related Reads:

- Backing the Bold Chapter 1 and 12 (2022)

- Fintech is Everywhere Part 2 (2022)

- SuperReturn China 2021 panel: Dissecting the influx of foreign capital into Southeast Asia (2022)

- Indonesia’s second wave e-commerce enablers part 1 (2022)

- Learnings on Cost-Cutting, Fundraising, and Growth for Startups in the Winter (2022)

- The Evolution of Indonesia’s Largest Tech-Enabled Logistics Network Growing Ecommerce Businesses with Shipper COO Budi Handoko (2021)

- Beyond the Go-To implications of the Go-To merger (2020)

- The New Normal with Dianping’s Zhang Tao and JAMM Active’s Chih Cheung (2020)

Paulo Joquiño is a writer and content producer for tech companies, and co-author of the book Navigating ASEANnovation. He is currently Editor of Insignia Business Review, the official publication of Insignia Ventures Partners, and senior content strategist for the venture capital firm, where he started right after graduation. As a university student, he took up multiple work opportunities in content and marketing for startups in Asia. These included interning as an associate at G3 Partners, a Seoul-based marketing agency for tech startups, running tech community engagements at coworking space and business community, ASPACE Philippines, and interning at workspace marketplace FlySpaces. He graduated with a BS Management Engineering at Ateneo de Manila University in 2019.