As the slump in public tech stocks continues and losses mount for global tech funds, even tempering investor appetite for early-stage tech startup investments, it becomes clear that winter has come early for startup fundraising, and it would be wise not to expect this to thaw soon.

At the same time, as we wrote in the Insignia Insights May 2022 Newsletter editorial, the last thing one should do in these times is to freeze to death.

The good thing is that the challenges for startups in 2022 bear similar resemblance to that in 2020, albeit the former potentially even long-lasting as the roots of this fundraising winter are more directly tied to the business models of tech companies vis-a-vis how they are being valued. There’s even the element of the 2019 investor “flight-to-quality” narrative that came out of WeWork’s initial IPO flop, which we also wrote about here.

That said, the echoes go beyond the impact and also in the way that startups can respond as investor belts tighten and the excesses of the tech bull run are uncovered. Be it amidst a pandemic or a bear tech market, at the end of the day, it’s all about building a business, and some things remain true regardless of the seasons.

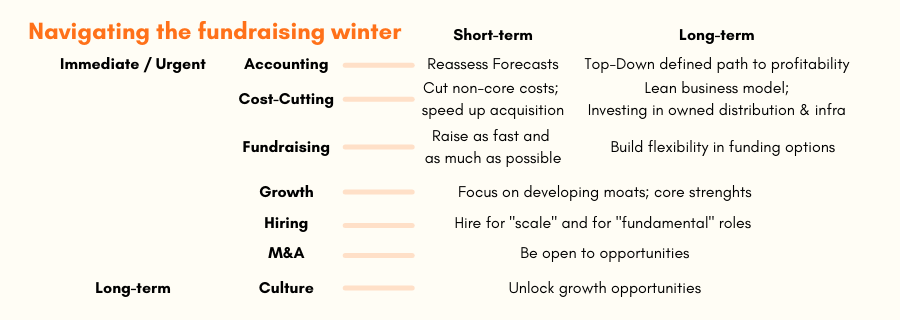

In this article, we picked up insights shared on our podcast on how our founder and investor guests navigated crises and strengthened their business fundamentals, curating them into seven main points, lined up from short-term to more long-term actions:

- If you have been lean, you don’t have to become lean. Assess company toolkit and runway and see if anything can be done immediately internally.

- Cost-cutting is not just about reaching a target spending; it should also be about enabling focus and fuel revenue generation and creating healthier margins.

- Create flexibility in fundraising options and maximize warm leads. Have a clear fundraising story with robust fundamentals (as documented in data rooms) for a (relatively) smoother fundraising process.

- Focus on building up company strengths and reducing risks in finding product-market fits, implementing go-to-market strategies, and achieving profitability.

- If you have the cash and margins, invest in hiring for scale and prioritize “fundamental” roles.

- If you have the cash and margins, be open to M&A buy or invest opportunities to beef up the business’s assets and advantages.

- Develop and maintain a company culture that unlocks growth opportunities.

Keep calm and re-assess your position

When Carro CFO Ernest Chew joined the fast-growing auto retail tech company in early 2020, it was right at the beginning of the pandemic, and so from the get-go he was faced with the challenge of navigating the company’s finances through that period.

Having gone through the ‘08 global financial crisis advising PEs and auto businesses as a banker, he was able to use learnings from those experiences.

Specifically, he shares on our podcast, “We looked at our toolkit. A few things that we did immediately: we went to conserve cash, slash all expenditures and cash up. We very meticulously went through expenses line by line. We cut down marketing immediately. We looked at payrolls. We monitored our cash position very closely. And we looked at monetising inventory as well. We went to banks to borrow even though we didn’t need to yet.”

The key here is that they acted fast and tapped into changes they could make internally, in other words, “looking at their toolkit.” That of course means having a clear view of what is happening in terms of the company’s cashflow, taking into account what is on paper (e.g. account receivables, invoices) versus what is actually in the bank.

In the case of Shipper, they were able to clear up a healthy runway from internal adjustments, as CEO Phil Opamuratawongse shares on our podcast. “So we, of course, did everything we could to make sure that the company had enough runway. I think that the number one thing for a business to sustain is to have runway, which fortunately we were able to create for ourselves.”

Having a clear view of the company’s situation does not just impact short-term actionables, but is also important to adjusting financial forecasts to account for the potential losses as a result of the bear market and adjusting expectations on account receivables and account payables for example.

In this regard, our founding managing partner Yinglan shares on our podcast the importance of being realistic with customer churn assumptions. “So I think the other thing is to be realistic about your customer churn assumptions and your sales pipeline, because it’s not only a demand shock, but be mindful that some customers may not be able to survive, or they are fighting for their survival. So they will have to cut costs massively. So don’t think in isolation, think in terms of your customers, they will also trim some expense.”

That said, this exercise of “looking at one’s toolkit” should not only be done in times of bear markets or crisis scenarios. As the adage goes, “if you stay ready, you don’t have to be ready.”

For Carro, it helped that from its founding, charting a path to profitability was embedded in the company’s goals (which it had also achieved amidst the pandemic), so it was easier for Ernest to make the necessary adjustments. On our podcast, Ernest credits the founders and senior management that enabled Carro to come out of the initial impact of the pandemic in an even better financial position.

“…we were “not swimming naked” – we had okay fundamentals. Most importantly we had cash and we were not over-levered…To our CEO, co-founders and senior management’s credit, we had always planned our businesses to be profitable or have a path to becoming profitable. We used the lockdown to seriously look at our OPEX, our fats and ways to improve our efficiencies. We came out of the lockdown leaner and meaner. In fact, our cash position did not deplete during the lockdown and we were free cashflow positive.”

Trimming the Fat: Healthy productive cost-cutting

Creating that runway and breathing room for the company is usually done through increasing revenues (offensive) or cutting costs (defensive), and in down markets, the latter is usually more accessible.

Off-the-bat, it’s important to trim costs not core to the key metrics of the company’s business, but even among these cost items, there are differences in terms of what will be easier to implement and practical versus what will require more careful planning. Reducing marketing budget might be easier to implement than reducing operational costs; freezing pay raises and cutting salaries are likely to require less procedures and planning than laying-off staff (ideally).

Vietnamese investor and entrepreneur Linh Thai, who came on our first podcast episode, shares that you can divide costs that need to be cut between those that are reversible (e.g. subscriptions) and the ones that need a little more handling and perhaps even some creativity because they impact livelihoods or long-term operations like rent or labor.

“I would start with cutting things that you can reverse, right? So for example, digital marketing, that’s easy. You turn off Facebook, turn off Google and then later on, you turn back on, right, so things that you can do with very little repercussions.”

“And then once those are cut, then then you look at the more serious ones like rent, labor and HR. And so you had mentioned some creative ways you can handle HR so instead of laying off everything, maybe try a furlough where it’s unpaid leave for a little bit. I know Vietnam has certain laws on that. So you want to look up the rules and laws on that.”

“Or you offer equity, or maybe you can turn them into a contract contractor, consulting contract, as opposed to full time, you know, just something so that you can maintain the ability to turn back on whenever the market starts turning around again. So that’s some of the ways you know, we think about expenses.”

Another layer of costs to think about is acquisition costs, and that involves looking at entire customer journeys and looking at how long sales cycles are taking and conversion from contracts to invoices to money in the bank. A lot of hypergrowth B2B companies fall into the trap of consolidating these different categories of revenue.

Our founding managing partner Yinglan emphasizes the importance of closing transactions fast and lowering acquisition costs for B2B companies to lengthen runways on our first podcast episode. “But I think you know, how do you think of, you know, closing transactions and faster sales lead time and lower customer acquisition costs, or by using inside sales reps for upselling and selling right, so I didn’t even think think through actually for the B2B companies, you know how you’re going to repurpose some of your salespeople or BD people for inside sales and online teleconference. And the trick here is to do it swiftly, rather than delayed right, and then you wait and see attitude isn’t gonna help you very much.”

Speeding up acquisition and conversion does not just potentially cut burn (especially for acquisition processes where time accumulates costs) but also drives revenues, which also another way to lengthen runway and improve financial fundamentals.

In the same way starving isn’t a healthy way to diet, it’s important that cost-cutting is healthy. Beyond simply generating more runway, a healthy way to think about cost-cutting is how can it ultimately help to improve focus on offensive or revenue generating strategies. In that way, it also has to tie into the company’s business model and operations.

Here companies that naturally have asset-light models and have been generating healthy gross margins are likely to have a smoother-sailing time navigating tighter belts.

On our podcast, social commerce platform Super CEO Steven Wongsoredjo talks about the value of “calculated growth” and focusing on “wise costs.”

“Of course, to be realistic as a CEO, after two to three years that I’ve been running the company, this year has been the year that I’ve seen a lot of uncertainty in the market. So what we do in the short-term goal has always been a calculated growth. As I mentioned before, we prefer healthy growth. It’s not all about growing your GMV or all of your sales at all costs, but now with “wise costs,” as we like to call it. So in every single transaction that we make right now at Super, it needs to be profitable, it needs to be giving us a good gross margin here and there.”

The “wise costs” approach worked to great effect for Super that they were able to allocate savings to expand their team.

“Therefore we can recycle those gold to actually expand the team. In December we were only 70 people, right now we have 130 people and we still burn the same, or even less. It means the strategy that we executed works well, and it started giving us results.”

Super’s VP of Operations Garret Koeswandi shares on our podcast how that “wise costs” reflects in terms of the social commerce company’s operational decision-making. Operational decisions need to have financial considerations, he emphasizes.

“But the thing is, working as VP of finance and operations, I think the biggest hurdle is that I have to analyze and judge my actions in a financial way. And I can’t just say, “Operationally, it makes sense. This is how it’s supposed to go.””

“I’m going to give you an example. We’re expanding to a different island. So it makes sense on a financial basis that the market for the island that I’m heading to is really big up north and somewhere in the middle of the island. But for the logistics, you have to stop at the south of the island. These complications and challenges — whether it makes sense financially to go directly to the heart of the island, but then operationally, it doesn’t make sense because you need to through the port first, and so how do you balance a position like that — are what I usually deal with on a daily basis.”

It also helps that embedded in Super’s go-to-market strategy and customer acquisition approach is leveraging on existing infrastructure to keep costs low, and then only investing in the necessary infrastructure once they hit scalability or economies of scale.

“So on a lot of the spendings in Super we are very lean on that matter and how we are able to do so is what I call “leveraging existing infrastructure.” What I see a lot of other companies do is that they want something done — let’s say they want to expand to a new market — what they do is that they just hammer on a lot of spending for new infrastructure, new human resources, and everything else. They just hammer down on that expansion.”

“In comparison to that, what we do is that we lean on existing infrastructure. We don’t just hammer down a new warehouse. What we do is that we go there and then we talk to one of the villages there and we were like, “Hey, I’ll give you 40 bucks a month if you just let me use your backyard. Is that cool?” “40 bucks. You can use the backyard.”

“And so we started using the backyards for our initial phase of expansion. We balance out the short term and the long term and in the short-term we use the existing infrastructure first and we keep things lean. With whatever existing warehousing, existing people or human resources, trucks that are already there, and distribution channels that are already there, we just piggyback on those existing channels.”

“Once we hit scalability or economics of scale, then we invest into our own networks and our own infrastructure, because by that time, our turnover would match our investment. And so we keep things lean. So that’s always been the approach that I personally adopt whenever we talk about expansion or making decisions about whether to invest at this time or whether we stick with the short-term strategy and keep patching things up until we hit that scalability point.”

The key takeaway here is that this lean decision-making is done at scale throughout the business. For venture-backed startups that are always juggling the demands of growth with cashflow, having cost-cutting as a habit or proactive measure or better yet, integrated into the very business model can make it easier to navigate growth even in bear markets.

And oftentimes cost-cutting involves making long-term, stable investments in owned infrastructure or distribution. In the case of Super, that has meant building their social commerce model with a logistics backbone, rather than depending on partners.

As Garret explains on our podcast, “This is why [Super’s] logistics backbone is very important because you can’t just rely on third-party logistics because they can be the solution, but they can also be part of the problem because you have a lot of these third-party logistics that only specialize in their zone and they might be the only player there. So it’s a monopoly for them. And so you have huge logistics costs over there if you want to approach those areas.”

“What we do is that we work with third parties, but we also have our backbone in-house as well that studies the market, studies the logistics, and we replicate what’s working in that market. And then we replicate it into an in-house team, which then saves efficiency. It depends of course on the area, but it could save up to 20 to 60% of costs which is a lot.”

Need For Funds: Fast and Flexible

If not enough runway can be created internally, it’s important to have a headstart in fundraising. In this particular bear market or fundraising winter for tech companies, while it doesn’t come with the same “digitalization” narrative valuation markup that the pandemic had, it is evolving in a relatively slower pace and there is time for startups to raise as fast and as much as possible before the environment get worse.

Raising fast is all about creating options and flexibility. It starts with having a good handle on which investors are out there or have the dry powder to make investments in a bear market. It’s important to tap into your existing cap table or investor pipeline to leverage warm introductions rather than banking on a funnel of cold outreach that could take months to convert.

On our podcast, investor Chih Cheung talks about focusing more on raising existing shareholders. “One, is your business model, fundamental, sound? If it is sound, I would definitely be more aggressive because everything else is cheaper. Your valuation is cheaper, so hopefully, you won’t need to raise money. I mean, what I recommend on the fundraising part is that I will not go try to talk to any new investors. If you need money or you need funding and you believe that you have the right business model, I would definitely go back to your existing shareholders. So one of the things I’m seeing is that if you have good backers, they’re willing to put in more money because they believe in your business model, and you have a good plan.”

Raising funding in a bear market also means adjusted pricing, which in light of “raising fast and as much as possible” may require more flexibility on the startup’s end as investors flex their leverage in an almost reverse dynamic from 2021. It has not yet come to the point of a field of down rounds as it was in the pandemic, but again the evolution of this bear market is slower than that in 2020, and sans the sudden digitalization markup (although as a long-term fundraising narrative, it will still be relevant).

Another way to raise funding is to look at other forms of financing vis-a-vis the company’s assets and business model. Ernest shares on our podcast how Carro thought about closing debt financing.

“Debt financing is actually a very important source of liquidity plus a cheaper form of capital than equity. We had a lot of assets going into the lockdown, whether in the form of financing receivables or vehicles that can be asset-backed. We didn’t want a “gun to our head” and suddenly be forced then to fundraise at unattractive valuation at, frankly, the wrong time.”

“From a signalling perspective, the ability for a start-up to secure close to S$150m debt financing facility really demonstrates strong conviction from banks who are generally very conservative backing startups.”

“So in a nutshell, I think that it’s important to think about that. But my advice is to raise that it’s important to have high-quality assets as collateral and think about being profitable, amongst other factors as well.”

While by nature, a startup’s hypergrowth and scalable business model is the reason it needs to keep fundraising and pumping in external funding, if the business has strong enough fundamentals to be self-sustaining throughout the fundraising winter, the latter option is a better option especially when it comes to saving on dilution.

Dianping CEO Zhang Tao shares on our podcast his experience in the global financial crisis. “So we kind of went through that a little bit. We were planning to raise a new round of funding in the next six months before the ’08 crisis but obviously we didn’t go through the funding; the funding [landscape] was dried up. Fortunately, operations were still kind of small. So meaning the burn rate is not that high. And so we were able to kind of, you know, increase the revenue source and just really push on the cost side. And we actually survived. And it’s a blessing in disguise, we actually didn’t really need money. So [we] saved a lot [on] dilution and actually the company’s healthier because we are going through more revenue and cash quality route.”

Read more advice on fundraising, especially early-stage and first ticket rounds from founders

Discipline in solving PMF, business model, and profitability risk

When it comes to bear markets, a lot of the risks that are inherent to startup hypergrowth are more likely to materialize and potentially even wipe out the value of the business in worst-case scenarios, from growth that isn’t built on product-market fit, to high topline revenue streams with thin margins, the lack of proper accounting processes and teams, and the lack of any significant moat. In a bull run, these weaknesses that emerge as the startup seeks growth-at-all-costs might be easily papered over by successive rounds raised on narratives and hype.

But as we’ve seen in the case of cautionary tales like that of WeWork or Theranos which in some proverbial timing had shows about them come out this year, and even in the companies that fell to the wayside in 2020, shifts in investor sentiments and market conditions can stop these trajectories in its tracks.

As we’ve mentioned before, this doesn’t mean that startups should just start paying attention to these risks in bad climate. Ideally these would inherent to the nature of how the company is run and grown, but in a fundraising winter where startup investors have more leverage and become more focused on gross profit and bottomlines, it becomes all the more important for management to have the bandwidth to focus on reducing these risks.

We cover three risks in particular in this article. The first is on product-market fits (not just the first one), and the costs of execution increase with every successive PMF, so it’s important to be able to iterate fast and minimize scrappiness as products mature.

Huy Nghiem, CEO of wealth management and investment platform Finhay, shares on our podcast how their approach to finding PMF and managing the costs around it have changed as their product has evolved.

“We are on the track to find a third PMF and I think it’s getting harder and harder compared to the first and the second ones. For example, for the first one we can fail, and it’s no problem at all. But at the scale that we are on right now, if we fail our third PMF, then it’s really hard to get back on our feet because we’re going to lose momentum and not to mention that branding will be damaged.”

“For example, we are working on a digital bank solution. And typically, if let’s say this is our first PMF, that it might take us three months to launch the product and we are okay if there are still bugs, but now it’s really hard for us to have trouble because we’re dealing with [financial services] and we try to minimize all the bugs and all the mistakes that we don’t want to deal with, so it costs us more time to actually launch the product. So it means we have to be more careful. So I think that’s one of the most difficult parts when trying to find the product-market fit.”

Pinhome CEO Dayu Dara Permata adds on the importance of PMF having “proof of profitability as reflected in positive unit economics”, as she shares on our podcast.

“…expand geographically only after the product reaches product-market fit and there’s proof of profitability as reflected in positive unit economics. If a product is structurally broken and current users are not willing to pay more than the cost needed to produce them, throwing money at the problem by subsidizing or giving incentives or giving gimmicks and expanding to more users once of the problem, it will only amplify it. We’ll see temporary growth, but also massive cash burn. And the minute we stop incentivizing, the growth will be gone. So I think that’s the second one.”

And for better or worse, figuring out this path to profitability is a day-one question, embedded in the go-to-market strategy, which leads us to our second risk: go-to-market risk. Startups might get away with costly GTM strategies on top of an early sizable war chest, but there needs to be a plan to stabilize revenues and achieve profitability.

Fortunately for most startups in Southeast Asia, playbooks exist globally to gain insights from, and even if it’s not the exact same product or business, patterns have emerged that could help point founders in the right direction.

We take the example of Aspire starting with credit on their path to building out their digital banking and financial services operating software, where this credit first approach echoes that of many other digital banks in emerging markets.

As CEO Andrea Baronchelli illustrates on our podcast, “So why was credit the first step? For many fintechs, regardless of the starting point, credit is often the destination for monetization and profitability. As Andrea mentions in the podcast, “Typically, there’s a lot of payments-led fintechs, right? But if you talk to them, they will pretty much always tell you that [they are] trying to monetize via credit. Either they have it in the plans or they’re testing it out, or they are doing a bit on the side just to add some revenues on the topline, but it’s pretty clear in the industry, that’s one fundamental way where eventually the path to profitability needs to come from.”

The third risk is around being able to build a secure enough moat or owned advantage. In the case of AwanTunai, this is something that they were well-positioned to do as their go-to-market (low-cost supply chain financing for FMCG downstream players) proved to be sustainable amidst the pandemic, and they had spent the previous two years leading up to the pandemic strengthening their risk management capabilities, which proved to be a key foundation for them to allocate resources to expanding their services as well.

CEO Dino Setiawan explains on our podcast how AwanTunai gained from building their expertise and strength in risk management and focus on FMCGs. “We really started our focus on FMCG back in 2019. One, it was a big enough segment: $80 billion per annum. Most of that in fact, more than 80% of that goes through the traditional kind of general trade route, as opposed to the 20% that goes through the modern retailer, which is the supermarket and modern convenience stores and e-commerce for that matter.”

“So it’s a very large space, very much underserved given the lack of any kind of digitized infrastructure out there. We talk about face-to-face transactions as they purchase inventory and cash payments. This is really a blue ocean that we play in. Now, we got lucky, because we actually focus on FMCG and staple foods and we were actually considering restaurants and cafes should we go into that then the pandemic hit, and clearly, that entire segment was significantly impacted adversely given the lockdowns.”

“And so given a lot of our painful experience with risk back in the early days, 2017, 2018, we took a very disciplined view on risk in 2019. I wanted my team to be the FMCG risk management experts in the country before we start expanding out into different industry segments. And that really just played out for us, because when the pandemic hit, we were simply in the FMCG segment, $80 billion per annum, that simply stayed open throughout all the lockdowns.”

“Well, as I mentioned earlier, for now, we’re simply under the assumption that COVID is going to be around for the foreseeable future. So we’re certainly staying focused on FMCG and staple foods. It’s still an $80 billion segment.”

And Dino really hammers home the keyword for to reducing risk: discipline. Whether it’s the discipline of ensuring product-market fit is found and go-to-market strategies are implemented on sound footing, this mindset can spell the difference between inherent startup risk being a burden or not.

Hiring for “scale” and “fundamental” roles

This discipline we just talked about is reflected in the product, organizational process, and business model of the company, but it begins and ends with people: beginning with the people who are hired and ending with the people who use the company’s products and services.

In a bear fundraising market, hiring costs are often frozen, but if the company has successfully created enough runway or margins (see the example with Super), there is room to actually take advantage of the shifts in talent distribution, thanks to other companies laying off their employees.

When there is that opportunity to hire, in the spirit of making long-term investments and reducing risks, it’s important to hire for scale. AwanTunai CPO Windy Natriavi explains this on our podcast.

“So given how scarce that product manager is, and even like how even rare a good product manager is always, really think that these are the people that you are bringing into your team. Here are the people that will interact with a lot of your team members and in a way, then it will shape the culture of how your company behaves and what, eventually you will be able to offer your customers.”

“So even though it’s very rare, but do think and hire in terms of scale, so don’t compromise or settle. So one question that I always ask is basically if I have 10 of these people or a hundred of these people, exactly like this, what would my company look like? What would my product look like? How would my customers react?”

“…But then the cost of actually hiring the wrong person is really big. And so I think, always think and hire in terms of scale. I think that’s the very fundamental advice that I would have.”A

A benefit of hiring for scale during this time is to be prepared for the market upturn. As Yinglan shares on our podcast in the context of the pandemic, “I think the other thing is also talent is much cheaper. So I would say yes, you should freeze hiring to cut burn, but I think always be open for exceptional candidates that are available. And try not to cut your engineers because in Southeast Asia engineers are a scarce commodity right? You want to make sure that you are prepared for the upturn when it comes, right. So you got to make sure that you do not only survive the downturn, but you also don’t want your capabilities to be really affected when the upturn comes.”

And speaking of capabilities to have, one important function in a period of tighter belts and greater scrutiny is the finance piece. A CFO or finance manager or head of the finance function is key to have a point person looking over the fundamentals as the company scales. Ernest shares his take on what makes a great CFO on our podcast.

“Everyone knows a CFO as the Chief Financial Officer. A great CFO in my view is also the Chief Future Officer. He / she is a true business partner, advisor, leader as well as critic to guide the company and people to become even stronger and more future-proof. In that context, the top 3 skills are:

- Be strategic. See the “big picture”. Link finance with strategy, operations, and even recruitment. Complement organic and M&A growth

- Forward-looking. Focus on growth (not just historical numbers) with a common sense approach to growth and risk planning

- Create a financial culture and discipline: Solid financial skills to create a methodical culture around analysis, interpretation and tracking of numbers and metrics.”

Got the cash? Keep doors open to M&A or investment opportunities

Zooming out, fundraising winters, juxtaposed with the drive for digital transformation, are an important period of development for relatively young startup ecosystems like those in Southeast Asia. They become litmus tests of survival and endurance, not just for emerging startups, but also industry incumbents.

And sometimes the answer to this question of endurance may not be to go on the path alone but to join forces.

Linh Thai, our first episode guest, shared this on our podcast as one strategy to stave off the uncertainty and exposed weaknesses that came with the pandemic. “I know of a company that basically, they have production, but their sales team is all offline. So now you can’t really go out and talk to people and try to make your pitch and so it’s really hard to sell their product. So then what if you find a company that’s very strong online, but then they just can’t sell their product, maybe they sell travel products where, you know, nobody’s really buying it right now. So then you each take what is strong and you work together, and you could potentially merge. And then if it works out, maybe you merge into a 50/50 company so that at least you survive.”

“The goal is to continue to stay alive until after this period, and then you can grow again. And you’ll see, I think a lot of companies, a lot of your competitors will go under and so if you are the one or two that’s remaining, even if you’re much weaker than you had been before, that’s still better than, you know, being dead. [It’s better] being super creative and trying to find any way you can to keep your doors open.”

As of late, this M&A and consolidation trend has been seen the most in Indonesia’s digital banking space, with fintechs rushing to pair up with banks. We recently wrote about M&A and investments as a path for fintechs to build up their digital banking stack.

As Yinglan shared in a Tech in Asia article: “This trajectory [of investing in Bank Bumi Arta] enables Ajaib to have stronger ownership over distribution and greater visibility into the full customer journey. This will not only create flexibility for users but also increase their long-term trust and usage, which is critical in developing monetization and profitability.”

So it’s good to keep doors open to M&A (i.e. buy) opportunities, especially if the company has the cash. M&As can beef up fundamental assets and growth. At the same time, it is still important to think of long-term value when considering these transactions.

Is your company culture unlocking growth opportunities?

One of the learnings from the 2020 pandemic impact was that the decisions around everything we have discussed previously are influenced by company culture, and obviously this will differ from company to company but the bottom line is that company culture should be able to unlock opportunities for growth.

In the case of Carro, the company encourages lean experimentation, as shared by Ernest on our podcast. “At Carro, and quite differently to large corporate and large MNCs as I alluded to experiments or small experiments are very encouraged. These experiments don’t cost a lot of money but we can learn and innovate, then a larger, incremental budget to support the product growth. Essentially the culture we have is you need to try and learn something out of these small experiments without deploying huge amounts of capital. So the risk of failures are generally lower.”

Then with AwanTunai, the culture of continuous iteration they developed over two years before launching their flagship product helped to navigate and quickly push out new growth opportunities amidst the pandemic.

As Dino shares on our podcast, “…what we’ve been focused on for the last month is really fast tracking, a lot of our digitization services…we’re actually fast tracking a fourth quarter product which is a full digital self service product to now. And the engineering team has really pulled out a rabbit out of the hat. They’ve gotten our first digital online product out there, where the merchants can not only get full loan applications and cashless payment on the app but also do online ordering of SKUs.”

“And it’s kind of a bizarre situation where this kind of crisis, gives us the excuse to really push for full digital operations where merchants who were used to face-to-face operations now have a really good reason to just essentially work from home, get on our app, order all the SKU from the app, essentially, have the wholesaler confirm which one inventory is available, and the merchant can pay using our app, cashless. And the suppliers will deliver the product to them. So that’s a full kind of like contactless experience that we’ve been able to deliver in a very short period of time. And we’ve just launched for one week but already a full 20% of our transactions is going through this whole automated ordering system.”

And for Shipper, CEO Phil Opamuratawongse frames it on our podcast as “bottom-up” culture enabling new ideas to emerge. “So for how do you continue to grow part, you have to be open to trying new things. A lot of the trial and error has to come from the team. You know, it can come top-down, but it has to be bottom-up. So I think we’ve been fortunate to create a culture where trial-and-error comes from bottom-up and we were able to come up with a few amazing ideas that have helped sustain the growth of the company.”

Read more about how company culture reflects in different aspects of startup growth

Thinking Long-Term

The fundraising landscape’s temperature is dropping, but when it gets cold the last thing you want to do is stay still. Decisions made during this period, whether cost-cutting, strengthening competitive advantages, M&As, or hiring from the tech talent exodus, can and will spell the difference between market leadership and falling by the wayside.

Just as discussion amidst the fallout of WeWork’s initial IPO attempt revolved around greater scrutiny and focus on paths to profitability, inflation and public market slumps are reviving this discussion. But the truth is these considerations should never really leave the table. After all, the best place for companies to raise money from is their customer base.

And for investors, it becomes more important than ever to have clarity with fund strategy (going back to the pitfall mentioned earlier of balancing quantity vs quality). It’s also less about investing in the best startup and more about being the right investor for the best startup.

At the end of the day, it pays to take consistent short-term actions with a long-term view.

Dino shares his long-term view on AwanTunai’s journey on our podcast. “I really see this journey as a marathon. And then that helps your mindset because then you start pacing yourself so you literally don’t mentally burn out. Because as you say, it’s a roller coaster ride. And I think what certainly helps in keeping this vision — that there’s a vision where you’ve got your whole organization culturally bought into achieving this vision and you start solving the problems.”

“There’s just a never-ending supply of problems out there, but what I’ve learned is we have solved — let’s say we go back two and a half years ago. What’s simply seen as insurmountable problems — we hadn’t solved risk yet, NPLs were horrendously bad back then. We hadn’t solved a source of lending capital yet. We only had one institutional lender and sales and distribution was an issue. It was almost the case that, well, okay, do we just change business models out of this, but we stayed true to the vision, knowing deep down that we should start solving the problems.”

“And we certainly applied a disciplined approach to resolving the risk problems. Now we’re best-in-class in terms of risk management. In terms of lending capital, it’s now actually triple-digit in the millions. We certainly solved that particular supply issue. And in terms of the sales we overcame a lot of the operationally difficult conditions. During the pandemic, we set up the infrastructure that now is set for scaling in 2021. So really pace yourself, keep disciplined. You’d get there in the end.”

Paulo Joquiño is a writer and content producer for tech companies, and co-author of the book Navigating ASEANnovation. He is currently Editor of Insignia Business Review, the official publication of Insignia Ventures Partners, and senior content strategist for the venture capital firm, where he started right after graduation. As a university student, he took up multiple work opportunities in content and marketing for startups in Asia. These included interning as an associate at G3 Partners, a Seoul-based marketing agency for tech startups, running tech community engagements at coworking space and business community, ASPACE Philippines, and interning at workspace marketplace FlySpaces. He graduated with a BS Management Engineering at Ateneo de Manila University in 2019.