Highlights

- Instead of looking at Southeast Asia’s gold rush as an inflection point, it’s more realistic to look at it as structural shifts in the region’s capital distribution, entrepreneurial class, and growth trajectories.

- As the growth-stage funding gap has been filled, the next gap to close in Southeast Asia’s investment value chain is the path from the private to public markets, especially with local indexes.

- Talents are catching up to the capital, but this has been ten to twenty years in the making, and continued support for individuals making the plunge needs to be present.

- Chinese entrepreneurs are becoming more sophisticated in their approach to starting up in Southeast Asia, but at the same time global-first companies coming out of Southeast Asia are becoming more attractive to investors.

- Early-stage and angel investing is becoming more democratized through various platforms and programs but there needs to be greater support from institutions and governments.

- The winners of a gold rush resist the temptations of the “rush” and focus on finding the real “gold”.

On 13 July 2021, for the Singapore Venture Capital and Private Equity Association (SVCA) Conference 2021, our founding managing partner Yinglan Tan sat on a panel alongside Kabir Narang, B Capital Founding General Partner and Co-Head of Asia, and Huang-Shao Ning, Co-Founder and Chief Angel of Angel Central on “Southeast Asia Venture Capital at an Inflection Point?” The panel was moderated by Doris Yee, the SVCA Executive Director.

“Southeast Asia is at an inflection point,” is a phrase that has been well worn out over the past few years of the region’s startup and venture capital landscape, thanks to the growth narratives we’ve been documenting all over this blog and our podcast. But what the recent developments in the region have shown is that “inflection point” is a misnomer. Southeast Asia will not suddenly blossom overnight into its own Silicon Valley or Shenzhen. Instead, a more realistic view we propose is that Southeast Asia is undergoing “structural shifts” that will take time to mature and need sustained and substantial interest to fully develop. And these structural shifts are just a natural part of the evolution of a tech ecosystem.

As B Capital’s Kabir Narang puts it, “I won’t say it’s an inflection point, it’s more of a structural shift happening. We’re starting to see some natural evolution start to happen. It’s not just about the next few years, It’s more of a 10-20 year story.”

So for those getting into the gold rush, the massive valuations and funding rounds, the SPACs are ultimately just the headlines — what long-term investors are really “betting” on are these fundamentals that are changing in the region: talent, funding, business models.

Capital: From growth-stage funding gap to public markets gap

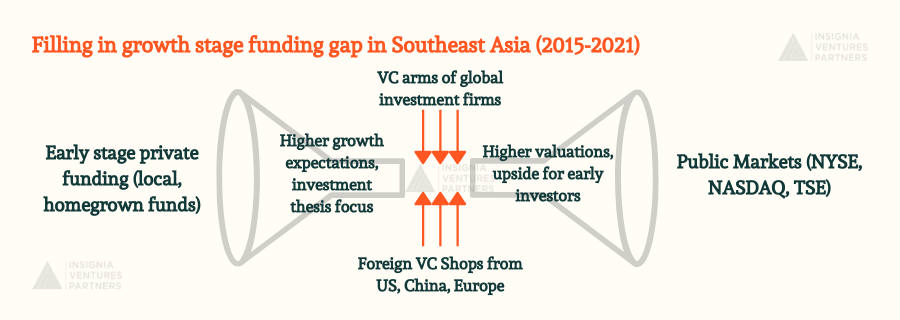

A large part of these structural shifts is the focus of the region on closing the gap between the private and the public markets. Only five years ago, commentary on Southeast Asia’s tech ecosystem was rife with the “growth-stage funding gap” problem, where startups fuelled up by seed and early-stage investors suddenly found themselves in a desert when raising post-Series A rounds.

But as Yinglan said in the panel, “Most parts of the funding life cycle have been filled. The gap is now the public stock market.” The likes of Softbank, Tiger Global, B Capital, and Prosus Ventures (Naspers) came in the last three years drawn by Sea’s public market exit and the slew of Southeast Asia unicorns that popped up in the latter half of the 2010s. Note that Google’s yearly SEA eConomy report began happening in 2016 — and it is likely that this was also part of this wave to fill in the growth stage gap. This helped fill in that “growth-stage funding gap” by creating more sources of funding for startups post-Series A, and the continued interest in Southeast Asia from global investors, strategics, and even family offices (some opting to invest directly rather than just becoming LPs) will bring in more optionality and boost the valuations of startups. It’s also worth noting that many of these growth stage investors are used to paying for higher valuations and larger growth targets, and for the global investors, their eggs are not all in Southeast Asia. These circumstances will likely keep the startup funnel going through the growth stage thin with more selective investors, in spite of the growth stage funding gap being filled.

Now the next gap to be filled is the road from growth to the public markets. The emergence of SPACs targeting Southeast Asia (drawn in partly by Sea’s 2020 public market performance) has catalyzed movement among bourses in this part of the world (IDX, SGX) to build up their initiatives to attract tech IPOs. That said, it’s important to realize that the development of these indexes — this structural shift to close the gaps from the private to public stock markets — will take time and several pioneering cases. The Bukalapak and GoTo IPOs if they proceed will be critical litmus tests and iterations for the IDX for example. And after this 2010s generation of unicorns go through their exits, there may be a slight exit “slowdown” where unicorns stay private a bit longer before gaining the volume and building the best possible equity story to go public.

“As Yinglan said in the panel, “Most parts of the funding life cycle have been filled. The gap is now the public stock market.”

Founders: From rare breed to greater interest

Talents are also catching up [to the capital], according to angel investor Shao Ning, who became a founder fresh from the dotcom crash in 2002 with a SaaS business. She shared on the panel how she and her co-founders could not find any funding sources so they went ahead and built the business simply through its revenues. They ended up selling the business ten years later, when the ecosystem in Southeast Asia was still quite early. Ten more years ahead, and while the funding landscape has radically changed, Shao Ning has also begun seeing more people taking “mid-career switches”. “For us, it’s very encouraging to see founders [making the switch] after their first job…it’s very encouraging to see interest on the ground,” adds Shao Ning.

While the risk for becoming a founder is still high, the risks and costs of starting a company (code + capital) has progressively been addressed by various institutions and organizations. Then apart from the support programs, incubators, and accelerators for pre-revenue, pre-product founders, another huge factor for this shift is the changing perception of becoming a founder mid-career.

It’s also very simply an increasingly attractive market to grow an internet business in, even if that business is not a venture-backed startup. B Capital’s Kabir Narang brings up the young demographic and increasing internet economy going from 30B to 100B in the span of a few years and projected to triple in the same amount of time.

That said, local ecosystems are still continuing to foster this entrepreneurial class, especially among native founders or founders who have been raised in their local markets. Even when it comes to entrepreneurial talent, it’s not so much an inflection point as it has been a structural shift that will continue to push for more professionals to take the plunge into startups.

Growth: From the “time-machine” thesis to the “global-first” approach

And while this growth in the internet economy fuelled by both capital and talent is a pattern seen across various markets, the reality that Southeast Asia has many other more mature markets to learn from has only sped up its development. A few years back many observers pegged China to be five to seven years ahead of Southeast Asia, but Kabir argues that the gap is not that wide for certain industries.

For industries that have similar fundamentals like edtech, with standardized testing, spending on education by parents, and other drivers, learnings are kicking in quicker. Then there are models like social commerce that are being played out almost simultaneously in China and Indonesia, especially in rural areas.

Of course there are the local nuances we emphasize time and time again, and this is something that Chinese tech entrepreneurs looking into Southeast Asia have had to adapt to themselves over the years since they began bringing their learnings and expertise to the region. Instead of directly importing models into the region, these entrepreneurs seeking greener pastures outside of China now look for local co-founders to get a better shot at success in the region.

Because these Chinese founders continue to hack away at the challenges posed by Southeast Asia, Chinese investors, especially those who have benefited from the mobile internet boom in China, are drawn to make more committal moves and putting money in more similar themes in Southeast Asia.

“A few years back many observers pegged China to be five to seven years ahead of Southeast Asia, but Kabir argues that the gap is not that wide for certain industries.”

While there’s this time machine mental model — the thesis being that what has happened in China will eventually happen in Southeast Asia, in the same way that investors in China also looked to the US for what might happen — that has dominated the conversation for investors, there’s another perspective on how the next billion-dollar companies could come out of Southeast Asia: a global-first approach.

Instead of taking a successful model elsewhere and making it “X or Y for Southeast Asia”, founders look at building businesses from Southeast Asia that could also secure customers beyond the region from day one. This applies to industries like SaaS or Fintech-as-a-Service where there is a lot more incentive for global customers (i.e. MNCs) to pay for the product or where these customers can benefit from the arbitrage of paying for a product from Southeast Asia.

These global-first players will also still likely have a significant base of customers within the region from which to build confidence in the product overseas, or perhaps as a result of headquarters also implementing product adoption in their Southeast Asia offices.

The evolution of these trajectories from more localization to globalization is a sign that the ecosystem is maturing and businesses in the market are maturing, but it will take some time for more businesses from the region to compete globally given the tougher competition and available capital interested in this trajectory to fuel their growth aspirations beyond Southeast Asia.

Regardless, businesses shouldn’t take these trajectories for the sake of, but rather base it on product-market fit and what really makes sense for the product and the revenues of the company.

“Instead of taking a successful model elsewhere and making it “X or Y for Southeast Asia”, founders look at building businesses from Southeast Asia that could also secure customers beyond the region from day one.”

Capital Part 2: The Democratization of Capital

Another interesting dimension of this “structural shift”, and more from the investor’s point-of-view, is the democratization of capital. There are more avenues for people to participate in angel rounds and platforms being built to accommodate significantly smaller check sizes (e.g. crowdfunding but with a price of equity). That said, Shao Ning points out that the playing field for angel investors still remains restricted, saying that the ratio of angel investors per capita is still significantly smaller in Singapore than in other developed markets.

Apart from more ways to invest in startups earlier in their life, the democratization of capital also refers to regional VCs investing more into having eyes on the ground, especially since the pandemic has wiped out the usual country-hopping regional VCs would do to run due diligence and close investments. These “eyes on the ground” aren’t just for investment teams, but also networks for reference checks to run holistic due diligence remotely.

“Shao Ning points out that the playing field for angel investors still remains restricted, saying that the ratio of angel investors per capita is still significantly smaller in Singapore than in other developed markets.”

Filtering through the noise is important in a gold rush

In any gold rush, it’s easy to get distracted — make premature celebrations, rush in an investment because of the valuation before making any proper due diligence, or shift investment thesis because of FOMO. But the real winners in a gold rush resist the “rush” and focus on the “gold”, filtering through the noise and focusing where they can find and grow real value. This means staying the course, supporting these structural shifts, doing proper due diligence, and being thesis-driven.

“The real winners in a gold rush resist the “rush” and focus on the “gold”, filtering through the noise and focusing where they can find and grow real value.”

Paulo Joquiño is a writer and content producer for tech companies, and co-author of the book Navigating ASEANnovation. He is currently Editor of Insignia Business Review, the official publication of Insignia Ventures Partners, and senior content strategist for the venture capital firm, where he started right after graduation. As a university student, he took up multiple work opportunities in content and marketing for startups in Asia. These included interning as an associate at G3 Partners, a Seoul-based marketing agency for tech startups, running tech community engagements at coworking space and business community, ASPACE Philippines, and interning at workspace marketplace FlySpaces. He graduated with a BS Management Engineering at Ateneo de Manila University in 2019.