Highlights

- The gravity wells of capital and talent created by unicorns in 2019 have become more widespread in 2021 as Southeast Asia’s startups discover how to “hyperjump” funding life cycles and more talent pours into the region’s ecosystem.

- Confluence of US and China spheres of innovation resulting from home market saturation and stricter regulations has not only brought in more talent and capital to Southeast Asia but also opens up more opportunities for startups to go global.

- Southeast Asia’s innovation landscape is growing and the velocity of this growth is keeping pace with the velocity of the activity within it so far. The VCs that fall behind are those that fail to ride these new waves.

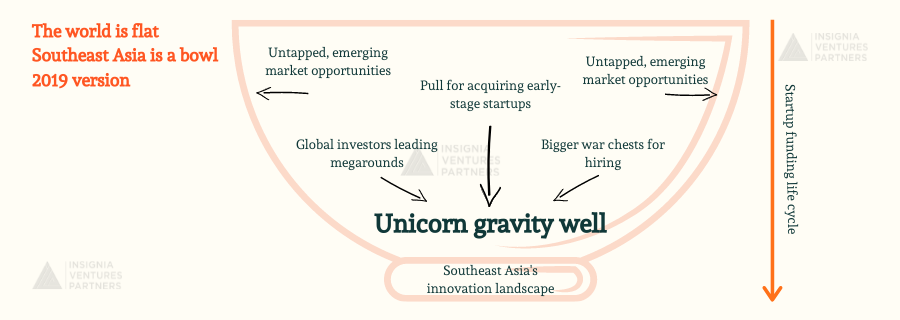

In July 2019, we published a short thought piece, “The world is flat, Southeast Asia is a bowl,” describing the region’s innovation landscape (vis-a-vis the flat or spiky landscape of the rest of the world) by capturing the creation of these talent (war chests and brand equity to hire top talent), capital (megarounds led by global investors), and even company (M&A deals with smaller companies) “gravity wells” by regional unicorns.

In July 2019, we published a short thought piece, “The world is flat, Southeast Asia is a bowl,” describing the region’s innovation landscape (vis-a-vis the flat or spiky landscape of the rest of the world) by capturing the creation of these talent (war chests and brand equity to hire top talent), capital (megarounds led by global investors), and even company (M&A deals with smaller companies) “gravity wells” by regional unicorns.

We arrived at the conclusion that while the gravitational pull of these unicorns would only increase moving forward, there remains a lot of space unaffected by the pull of these unicorns and the value of Southeast Asia’s innovation landscape for early-stage venture capital lies precisely in opportunities untouched by unicorns (e.g. Indonesia’s rural economy).

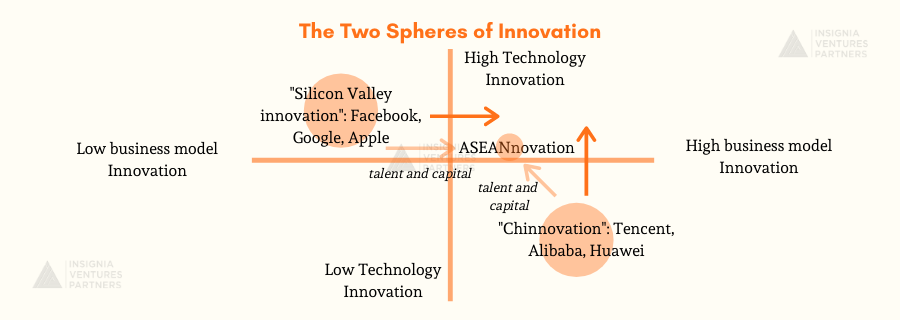

Then in November 2020, we wrote about the impact of the increasing bifurcation between the US and China spheres of innovation on Southeast Asia in another thought piece, “Unifying The Two Spheres Of Global Innovation: The Role Of ASEANnovation On The World Stage,” with tech companies and investors in the former finding green pastures in the latter amidst trade wars. The main examples we gave then were the diversification of supply chains into Vietnam and the movement of headquarters and talent into Singapore.

This year, we’ve seen both frameworks we described in these two articles — the deepening gravity wells and the confluence of the US and China innovation in Southeast Asia — not only evolve but also affect each other, with the pandemic as a catalyst.

In this article we revisit these frameworks, develop them further given what has been happening this year thus far, and most importantly, outline the opportunities for early-stage venture capital and early-stage startup founders in Southeast Asia offered by the developments in these frameworks.

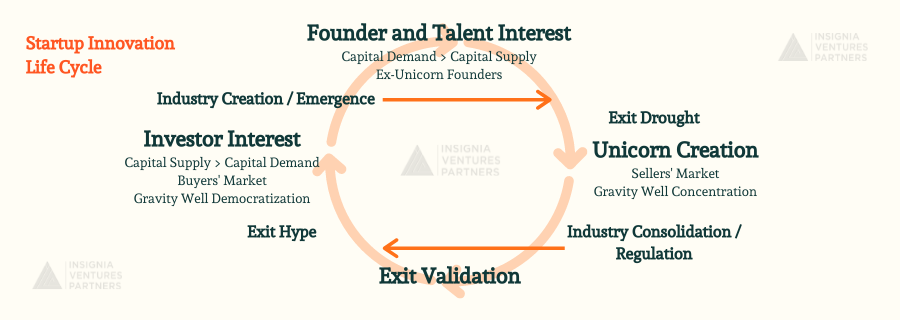

Southeast Asia’s startups have discovered how to “hyperjump” funding life cycles

We’ve seen how the gravitational pull in Southeast Asia created by the 2010s generation of tech unicorns has expanded to the war chests of other tech startups. The valuation markups in 2019 that primarily affected the post-Series C rounds of unicorns have increasingly become more common in 2021, impacting even earlier stage rounds (seed to Series B), especially where US and global venture capital and private equity investors are involved.

This has largely been driven by public market activity becoming more pronounced in Southeast Asia, from the 2020 performance of Sea Group on Wall Street to the movement of first-generation unicorns (i.e. PropertyGuru, Bukalapak, Traveloka, Grab, GoTo) to the public markets catalyzed by the former, Southeast Asia-focused SPACs, and local bourses making more significant adjustments for tech companies.

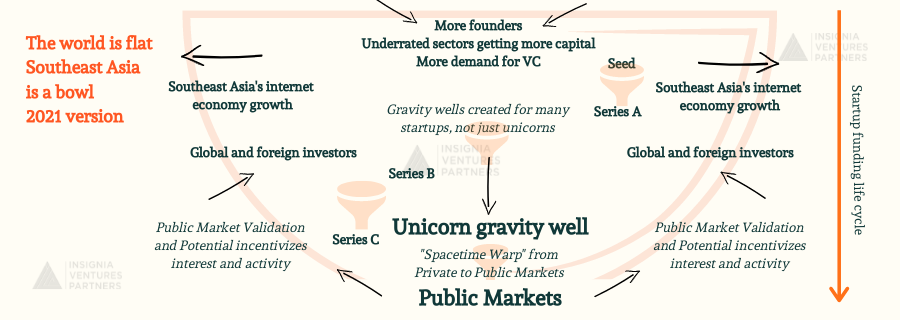

To put it into the context of our 2019 discussion on unicorn gravity wells — a “spacetime warp” has been opened up from the private markets to the public markets. To be fair that pathway has always been there (i.e. Sea went public in 2017), but the mass of the companies concentrating at the deep end of Southeast Asia’s gravity well had not been significant enough — until now.

This opening up of Southeast Asia’s bowl to the public markets has created that current of more capital to be committed to the region, where we see the likes of Hedosophia, QED, White Star Capital, Cathay Innovation, and Ribbit Capital coming in assigning or recruiting people to focus on early-stage deals Southeast Asia as it takes a more significant portion of these US and European firms’ investment interests.

The edges of Southeast Asia’s bowl are also flattening with this diversification of capital sources, not just from global investors but also local funds. We’ve seen the rapid deployment of the dry capital that was accumulated over 2019 as LPs hopped on the private market fundraise balloon in 2018, as well as the creation of smaller, more focused funds, usually tied to local family offices and conglomerates (especially in Thailand and the Philippines).

The vacuum being created by the first generation of unicorns heading to the public markets is quickly being filled up by local firms teeing up companies to global marquee investors presumably used to buying at higher prices in more mature markets. This has ushered in the second generation of unicorns this year (e.g. Carro, Flash Express, Nium) many of whom achieved a billion-dollar valuation at a much faster pace than the first generation.

This means that we can expect this “spacetime warp” from the private to public markets to also create smaller warps across the funding life cycle, enabling startups in the region to raise bigger and faster. Perhaps over the next few years, we may even see tech startups access the public markets even before becoming a unicorn if public market investor interest matches the enthusiasm of private market investors. In a way, it seems as though Southeast Asia’s tech startup ecosystem has finally discovered how to “hyperjump” through the funding life cycle, and the “hyperjump technology” is no longer just available to unicorns as it was in 2019.

The short-term benefits of the global investor markups and early-stage funding diversification are obvious: more incentive for founders to build companies in the region, meaning more demand for venture capital and more demand for talent to grow these companies. But then the biggest risk here is when the velocity of fundraising valuation outpaces the velocity of actual company growth and the velocity of Southeast Asia’s internet economy growth (oh no a bubble!)

That said, we are still at a point where Southeast Asia’s internet economy still continues to grow at an increasingly rapid pace, and this is largely due to the momentum created by the first generation of unicorns amidst the pandemic, funneling new online consumers and increasing confidence in businesses to adopt emerging digital platforms and solutions.

Some of the predictions made by everyone’s favorite report — SEAconomy by Google, Bain, and Temasek — are already being broken and we can expect this to continue to 2025. This points towards demand for digital solutions to continue keeping up with investor interest, at least in the next five years. So in the meantime, a velocity equilibrium is being maintained in spite of the massive influx of capital this year.

Southeast Asia is a bowl framework 2021 version. Equilibrium is maintained so far as influx of capital is balanced out by continued growth of internet economy.

Three opportunities for early-stage venture capital in Southeast Asia:

- Short-term benefits of bringing in global marquee follow-on investors that increase markups to offset or even exceed the impact of dilution on returns, especially as they move in earlier rounds. Selling a buyers’ market can be lucrative, but should also be strategic. This markup increase also increases the velocity of unicorn creation and likelihood of earlier exits in the fund life, potentially increasing LP confidence in local funds and resulting in even more dry powder among local VCs. The risk here is that as global investors move earlier in the value chain there will be more competition in pricing, but just as with local startups, local firms have an edge in terms of having more at stake in the region and a localization advantage in terms of working with startups in the region.

- More space for local VC firms to invest in niche or emerging areas like crypto or agritech or femtech and sell these sectors and companies operating in these markets up the funding value chain. The risk here is finding the right spaces that align with the investment thesis and balancing allocation against hotter sectors.

- More pathways to exit and faster timelines to take advantage of increase in velocity of unicorn creation and ability of companies to exit earlier. The risk here is whether the company’s growth can actually keep pace with investor demand.

Three opportunities for early-stage startup founders in Southeast Asia:

- More sources of capital to access, and many who are willing to pay above market, but are they truly valuable investors in the long-run? And if they are leading the round, how committed are they to you as their portfolio company?

- More attention is being given to industries and sectors that previously had no “gravitational pull” of their own in terms of venture capital. Underrated venture-backable spaces can be valuable blue oceans for startups.

- More options to exit in the years to come, but figuring out which is best for the business ties directly to the vision and goal of the founders from day one.

US and China confluence opens up Southeast Asia influence

Apart from the private to public market “spacetime warp” opening up, the increasing confluence of the US and China innovation spheres into Southeast Asia has also been reshaping Southeast Asia’s bowl. At the time we published the piece on the bifurcation, Joe Biden had just been elected president of the US and China had just halted Ant Financial’s IPO in its tracks. Since then, we’ve seen the Chinese government take even more decisive action to wield control over its technology ecosystem and also build a more self-reliant industry (e.g. semiconductors and chips), and in the US, regulatory scrutiny on tech companies has also intensified, more so on those coming from China looking to list on Wall Street.

What’s new in terms of this bifurcation and the resulting confluence of these spheres of innovation in Southeast Asia is that it is not just an influx of capital or investments, but also of talent, thanks to healthy amounts of push incentives like an increasingly saturated market (more unicorns that came out of Southeast Asia than China this year, a new record) and pull incentives like the public market potential we discussed earlier.

The talent coming from China and the US takes the form of (1) investors setting up regional headquarters for their firms, (2) tech company executives relocating to expand their presence in the region, (3) HNWIs and family offices setting up Asia offices, (4) former founders, executives, or even employees of big tech companies looking to start new companies in Southeast Asia, and even (5) professionals (returnees among them) looking to be part of an emerging market venture.

Each of these groups impacts the developments in Southeast Asia’s gravity wells and startup funding life cycle as we described previously. Investors leading Southeast Asia investment for global firms relocating to the region itself signifies direct contact and stronger commitment towards founders in the region, opening up more of these smaller “warps” for startups to “hyperjump” in their fundraising journey.

Apart from global investors setting up local headquarters to widen the competitive landscape for venture capital, the same trend is also happening in terms of tech companies setting up Southeast Asia offices, or moving their Asia headquarters to cities like Singapore. This presents welcome competition in the market and also opens up opportunities for emerging tech startups to build adjacent to these global players, with the latter becoming customers or partners of the former.

HNWIs and family offices, as we’ve covered in past articles like this one, are also looking to participate in the diversification of early-stage venture funding, either by becoming LPs, setting up their own venture capital funds, or participating directly in fundraising rounds.

Then there are also operators, especially from Chinese tech giants, looking at Southeast Asia to start new ventures. This is not a new phenomenon, but we can expect an increase of these types of founders to be pulled in by the region’s gravity well and offer their past experience and built up expertise to company building in the region. That said, local VCs are always cautious about funding these “tourist” founders unless they have local co-founders or members in their management team who are able to navigate the intricacies of Southeast Asia.

Finally, there are professionals who are simply drawn to working in Southeast Asia’s tech companies, whether as entry level employees, remote workers, founding team members, or senior executives. These professionals could potentially upskill companies especially if they come from a deeptech background — the kind of background that has traditionally been lacking in Southeast Asia. We’re seeing more tech startups like fintechs for example looking to hire AI experts, and so there’s increasing demand for operators who can lead technological innovation within a startup. With the trend of markups and larger funding rounds in the region, the startups with bigger gravity wells are more likely to bring in the better talent.

This layer of talent influx on top of the capital influx means that the space occupied by Southeast Asia’s innovation landscape will inevitably grow bigger, ultimately creating a virtuous cycle of proportionally increasing demand for talent and capital.

The interesting effect of the confluence of these spheres of innovation is that there will also be more opportunities for local startups to go beyond the region itself, especially for startups that offer solutions that can be competitive on the global stage. With more of the world participating in Southeast Asia, the more Southeast Asia is able to participate on the global stage. It may not be an equal and opposite reaction, but with what Southeast Asia is able to take in, there are also opportunities to bring beyond the region.

Three opportunities for early-stage venture capital in Southeast Asia:

- Local VC firms developing into or positioning themselves as platforms for their portfolio companies to leverage US and China confluence, from talent to follow-on capital. Data-driven tech stack will also have a large role to play in navigating the increasing noise in the region.

- Local VC firms as platforms to help family offices and HNWIs invest in startups, either through their funds or directly as co-investors or follow-on investors.

- More professional interest in venture capital as demand for capital increases and the critical mass of founders increases as well.

Three opportunities for early-stage founders in Southeast Asia:

- More expertise and professionals in areas that are not as populated in the region but whose applications are in high demand (e.g. AI and data analytics being an example).

- Easier to sell to Chinese and US companies that are setting up HQs in Southeast Asia as customers, more opportunities for B2B or enterprise startups.

- More capital and talent are available to support global-first growth trajectories.

Southeast Asia’s bowl is not cracking, but growing bigger, so the more, the merrier

It is worth noting that the entry of US and China into Southeast Asia in terms of talent and capital is not new, nor has it always been successful. A decade ago some global marquee investors tried dipping their feet into the region but the activity did not explode into the gold rush we are seeing today.

That said, there will always be space for local VC firms and investors with the long-term conviction and a compelling value proposition for founders in the region. There may be less of an early-mover advantage for sectors that are already flush with capital like generalist ecommerce, but one of the great things about being an investor, and more so a founder, in a fast-growing, diverse market like Southeast Asia, is that there are constantly new opportunities for ventures to build, not just locally, but now globally as well. Southeast Asia’s bowl is growing and the velocity of this growth is keeping pace with the velocity of the activity within it so far, so the bowl will not crack anytime soon. The VCs that fall behind are those that fail to ride these new waves.

Competition is not the limiting factor for venture capital in the region, and one could even argue that there are not enough VC professionals in Southeast Asia — that’s why you have emerging programs like the Insignia Academy, a VC accelerator. Rather, the limits investors need to look out for are their own investment strategies or theses and the socio-economic trends and behaviors around these markets. In this regard, we see value in thesis-driven investing and focusing more on quality and performance rather than a spray-and-pray approach, which funds and firms with more dry powder and bigger operations would be better suited to compete on.

Paulo Joquiño is a writer and content producer for tech companies, and co-author of the book Navigating ASEANnovation. He is currently Editor of Insignia Business Review, the official publication of Insignia Ventures Partners, and senior content strategist for the venture capital firm, where he started right after graduation. As a university student, he took up multiple work opportunities in content and marketing for startups in Asia. These included interning as an associate at G3 Partners, a Seoul-based marketing agency for tech startups, running tech community engagements at coworking space and business community, ASPACE Philippines, and interning at workspace marketplace FlySpaces. He graduated with a BS Management Engineering at Ateneo de Manila University in 2019.