Highlights

- An increasingly competitive venture capital landscape requires greater differentiation in value propositions. The good news is that battles are not won just by the term sheets.

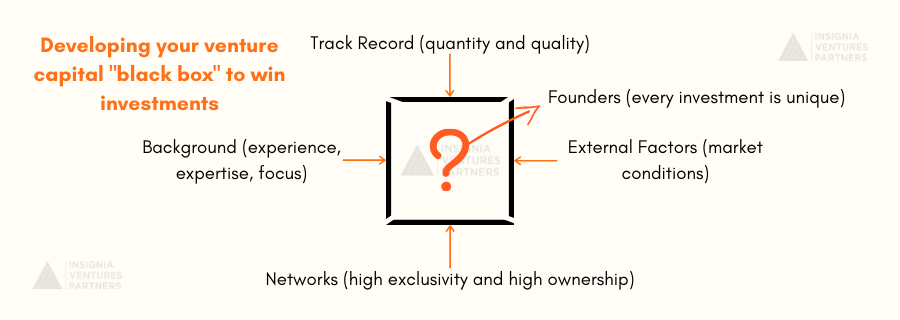

- Venture capital is filled with black boxes, and you can build your own tailored to your background, networks, and track record as part of your value proposition to founders.

- Building your own black box is a two-way street, adapting to the needs of each founder you interact with.

Over this past year, we’ve been writing about the influx of venture capital into the region and the increasing population of talent looking for this capital to supercharge their startups. This has resulted in an interesting dynamic for the venture capital industry in Southeast Asia.

On one hand, the concentration of capital in the region has brought to the spotlight (read: valuation markups) industries like healthcare, enablers, and logistics, which were previously underserved relative to hotter landscapes dominated by the region’s first generation of unicorns.

On the other hand, as the sources of early-stage capital have diversified with more types of investors hopping on the bandwagon (e.g. family offices) and typically late-stage folks coming in earlier rounds, there’s more competition over these emerging investments opportunities.

With the backdrop of this increasing competition among venture capitalists in Southeast Asia, it’s easy to wonder, especially as a venture capitalist starting out or a professional looking to make it in the industry, how one can compete with larger funds or firms in winning over founders of wildly attractive startups.

The short answer? The battle does not happen on the term sheets.

The long answer? The reality of venture capital is that it is an industry filled with black boxes. While there’s just as much content from tweets and Linkedin posts to podcasts and books ruminating on the formulas behind every investment, the truth is that even with a methodical and thesis-driven approach, every pursuit of investment is a complex and personal affair. Not having the aggressive terms to pitch does not count you out of an investment if there is more to offer on the table.

Developing your own VC Black Box

To every potential investment, venture capitalists don’t just bring term sheets to the table. They bring their backgrounds, networks, and their track records. For the discerning founder, these highly contextual assets can play an important role in deciding the long-term value of having a venture capitalist on the company’s cap table or even board of directors, more so than the term sheets themselves. It is not uncommon for founders to choose a local VC over a marquee investor as a lead investor because of these other advantages the former brings to the table.

To become a competitive venture capitalist, having your own well-defined black box, aligned to the needs of the founders you’re looking to invest in, can be valuable in convincing a founder to partner with you.

This black box spells the kind of commitment or working relationship a founder can expect beyond the initial injection of capital. For example, Eric Acher, co-founder and managing partner of monashees, Brazil’s first VC firm, shares on our podcast how the firm helped Brazil’s first unicorn and exit, 99.co, as the company went from their seed round to unicorn-hood and finally an acquisition by Didi.

“We ended up helping 99 on many fronts. We were very much involved, significant equity and the board seat from the beginning of my partner Carlo. And we helped with our knowledge about marketplaces. In the beginning, we had invested for a few years in marketplaces. We knew how important it was to start on the supply side. It was very important to reduce friction, to bring the drivers, start it only with the taxi drivers and then migrate to the other drivers. That knowledge of marketplaces helped entrepreneurs think about it. Also we helped bring Tiger [Global] as a follow on investor. That was another help. And then finally we helped bring talent. We brought a very important COO that became the CEO of the company, Peter Fernandez. We helped him join the company. And so talent, capital, and some market and industry knowledge. Those were the points that we were able to help entrepreneurs in building, but it’s their merit in building an incredible company, that was our first unicorn.”

In the case of monashees, the expertise the firm had built from past experience investing into marketplaces paid off in supporting 99 as the ride hailing company built out their platform. It also likely helped that the firm had been a mainstay presence in the ecosystem by the time 99 was raising its seed round, and the partners themselves had already built a track record and network geared towards Brazilian startups.

Background to Build Affinity with Founders

The working relationship a founder can expect from partnering with any venture capitalist is tied to the latter’s personal background and the VC firm’s aggregate experience as well. For Rajive Keshup, his background as an exited founder and CFO of several tech startups in Southeast Asia contributes to his own black box as a venture capitalist, as he describes on our podcast.

“I approach [my work as a venture capitalist] with a little bit more empathy and a little bit more understanding or unpacking of the chaos. As a startup founder, I’ve had to do payroll and make payroll and that’s never fun when it’s close to the end of the month and you’re trying to figure out if cash flows enough. And at the same time, as CFO and going out and raising capital, I can understand what goes into the narrative building and parts of the story and what you omit and do that whole dance. And so I feel like that automatically clicks with management teams cause they say, “Oh wait, you’re a little different cause you’ve been here.” And I’m like, “Yes, I’ve seen all the tricks and all the bullshit, let’s cut to the chase.” That part for me has been different and I look at things slightly differently compared to some of my peers. I look at things through, “If I was running this business, what would I do differently?” And I feel like I can make that mental bridge only because I’ve done that in other parts of my journey before.

Rajive’s background as an ex-founder and startup operator enables him to have greater empathy when working with founders, having been in their shoes in both good times and bad. The best backgrounds for a venture capitalist allow them to build affinity with the founders they work with, whether it’s being an operator VC having shared experiences or being a sector-focused investor capable of filling in the gaps of expertise or knowledge of the founders and the management team in a specific field.

Apart from your personal background, the aggregate experience and focus of the firm also contribute to the venture capitalist’s black box. For example, an Indonesia-focused VC firm and a global investment firm would have different value propositions for the founders they approach, regardless of the individual leading the deal.

For the aspiring venture capital professional, it is important to be able to ensure that the firm you’re working for also aligns with your own expertise or background. It doesn’t make sense to work at a fintech-focused fund if you don’t have any fintech background or expertise unless you’re rising through the ranks and are looking to build that track record in fintech.

In more sector-agnostic firms it also makes sense to apply to those that have not yet covered your field but are interested in doing so. For example, having experience building companies in Southeast Asia would be attractive to a global firm that is looking to invest in companies from the region but also needs someone on the ground to help them navigate the local nuances of the market.

Best Practices

- Ensure your background and expertise are well-defined and align it to what founders find valuable for their company.

- Work with a firm where your background and expertise can be best maximized (either aligned to the focus of the firm or filling in a gap in investment strategy).

High-Value Networks

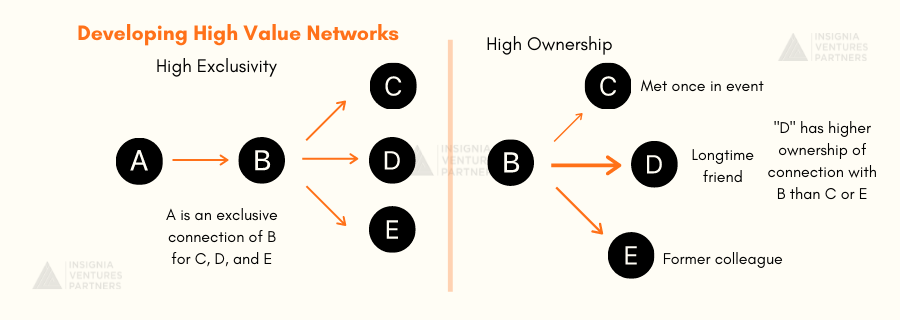

Apart from experience, another element of a venture capitalist’s black box is networks. When evaluating the value of a network, the most effective ones have high exclusivity (i.e. are there other, easier ways to reach this connection?) and ownership (i.e. will they take your calls or quickly respond to your messages?). These networks can be deeply localized within a market (e.g. having strong connections to regulators and institutions), specific to a sector or vertical (e.g. being able to source experts in a specific field like AI), or spread across both markets and verticals.

Just as with your background, the networks you have also play an important role in shaping the kind of relationship a venture capitalist will have with the founders they work with, because a lot of the support founders will need (and find valuable) often boil down to needle-moving introductions, from potential hires for leadership roles to decision-makers at potential customers and follow-on investors. This means it’s important to align your networks with what founders need given the company’s stage of growth.

Networks can be built in various ways, from direct outreach (e.g. networking in events or through personal contacts and referrals), or indirect positioning (e.g. pushing out thought leadership or building a personal brand attracting a certain audience that could be a source for high-value connections).

Best Practices

- Focus on making connections that have high exclusivity and where you have high ownership.

- Diversify your networking, from direct connections to indirect audience and brand building.

Track Record

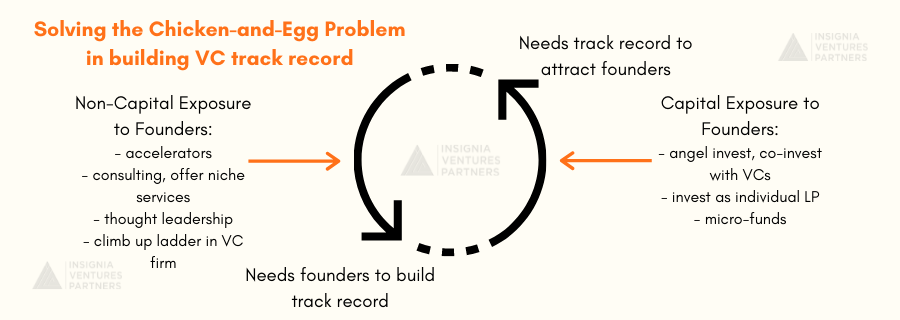

The third element of a VC black box is investor track record. Track record can be summed up in three questions: (1) how many other companies have you backed and exited, (2) how much of a commitment did you have with these companies, and (3) how big did these companies become? These questions essentially cover both the quantity and quality of a track record.

Another way to think about track record is as a VC’s referral list. Venture capital is a service industry, and businesses in service industries will often get new customers through reviews and referrals. In the same way, discerning founders will often run reference checks on potential investors by reaching out to founders they have worked with or are currently working with. In a Clubhouse session earlier this year, Yinglan illustrates a simple but effective way to encapsulate this referral list.

“[When you’re fundraising], you’re finding a partner and some of these partnerships last longer than marriages and it’s very easy to find folks who clap and cheer you on when things are going well, but it’s harder to tell what they [will] do when things go south. [That’s why] when founders ask about us I give them our CV: the names of our founders and their WhatsApp numbers, ten of them. I give my rap sheet, [and tell founders], these are the ten founders I’ve worked with. [Contact them]. I suggest you do the same for the investors that have expressed interest to invest.”

A rap sheet of founders you’ve worked with will not only speak to what you have accomplished, but also to how instrumental the other two elements of the venture capitalist’s black box, background and networks, have been to your work as a VC.

The hardest part about building a track record is getting started. It’s a chicken-and-egg problem, where founders are more likely to work with VCs that have made investments before but at the same time you need to win over founders first in order to make those investments. Given this challenge, those looking to break into venture capital need to be able to create that founder exposure without necessarily having to commit capital — though it certainly helps to angel invest if you have the spare cash to do so. Rising through the ranks in a VC firm and working with partners on investments is the obvious route, but you can also join other environments where there is a high concentration of interaction with founders like VC accelerators like Insignia Academy.

Best Practices

- Communicate your track record by putting together a rap sheet of founders who would recommend you to other founders.

- If you have no track record yet, put yourself in environments that allow you to interact with founders even without having to commit capital. If you have the capital, you can dive in and angel invest and co-invest with VCs or be an individual LP in a VC fund!

Uncertainties loom large

In venture capital, uncertainties loom large. There are a lot of external factors beyond the control of the individual investor, especially when they are working in a large firm and are not the key decision-makers. Two examples of these external factors are the market conditions and also the consensus nature of how most venture capital deals are decided. Eric Acher from monashees shares on our podcast one of his biggest misses as a venture capitalist on our podcast and the role the market and general consensus of the firm played in missing that investment.

“Using the criteria of the value of the company today, my biggest miss was Mercado Libre [in their] Series B when I was at General Atlantic (GA) in 2000. So I took that opportunity to the investment committee of GA. This was right after the crash. Mercado Libre was raising a Series B and we discussed it, but it was very hard to make the decision at that point, psychologically. We knew the founders. [They were] incredible entrepreneurs. There was a big opportunity, but right after the crash, it was very hard to make the decision. So we passed and then seven years later, they did their IPO. Today they are a US$70, 80 billion company. I think they’re the largest tech company outside of the US and China.”

These external elements also factor into why there are black boxes in the first place, and why there are no surefire formulas to securing investments or making the right investment decisions in venture capital.

It’s not just about winning battles, it’s about building lasting relationships

Building your own black box as a venture capitalist is not just a personal affair that requires a deep understanding of your background or value proposition, development of your networks, and accumulation of a track record. It is also a two-way street.

Entrepreneurs define the venture capital industry. They are on the steering wheel, putting their lives on the line to lead an expedition into the unknown, and venture capitalists are just in for the ride, pitching in their special fuel to get to the destination a little bit faster, and once in a while pointing at the stars that lead the way. As Don Valentine put it in the documentary “Something Ventured”:

“It’s nice to sit in the glow of your adulation, but without entrepreneurs, you’re nothing. You have to have these real people, with the ideas and willingness to commit their life.”

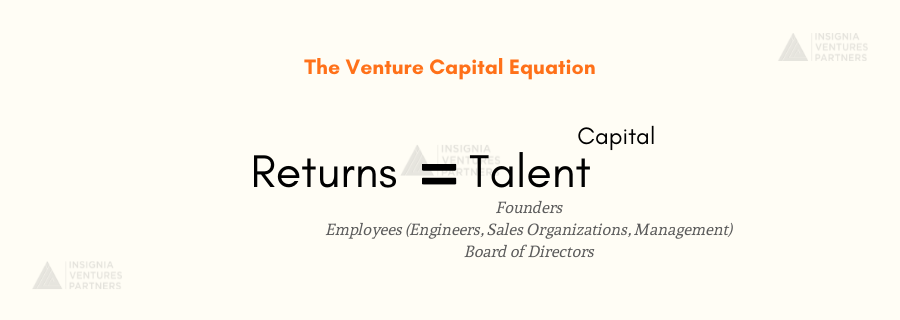

In the equation of venture capital, capital is only as efficient as the talent it is invested into. A US$25 thousand check into a team capable of enduring, pivoting, and growing through the seasons can do exponentially more than a US$25 million check into a team that breaks down at the first hiccup or cannot move fast enough. That talent begins with the founders but also encompasses the capabilities of the engineers they bring on board, the sales organization they build, the country managers and senior executives they hire, and the board of directors they bring together.

Looking at the business of venture capital this way is important in developing your VC black box, as your approach should always adjust and adapt to the founder on the other end of the line or sitting across from you.

Going back to our initial question at the beginning of this article on how to convince founders to take your offer in a competitive round or environment, perhaps the answer after all is to focus on the long game. Eric Acher describes this long game on our podcast.

“I’d say it’s very important to have a collaborative approach to build lasting relationships with founders and always thinking about maximizing the long-term not maximizing the short term. It’s not being transactional, being collaborative. You may lose here and there in a short time, but it will really build the relationships and the reputation that you need in the long run as a VC and especially in Latin America, where traditionally financial investors had all the bargaining power and were never collaborative. That makes a big difference.”

Paulo Joquiño is a writer and content producer for tech companies, and co-author of the book Navigating ASEANnovation. He is currently Editor of Insignia Business Review, the official publication of Insignia Ventures Partners, and senior content strategist for the venture capital firm, where he started right after graduation. As a university student, he took up multiple work opportunities in content and marketing for startups in Asia. These included interning as an associate at G3 Partners, a Seoul-based marketing agency for tech startups, running tech community engagements at coworking space and business community, ASPACE Philippines, and interning at workspace marketplace FlySpaces. He graduated with a BS Management Engineering at Ateneo de Manila University in 2019.