At the turn of the millennium, a Chinese American still fresh into his career and working at the time for the San Francisco County made a fateful decision to fly to Hangzhou and become the first American to join a small company of around 50 other people to build a then little known business marketplace called Alibaba.com.

More than twenty years later, Brian Wong, former longtime executive, assistant to Jack Ma, founder of the Alibaba Global Initiatives division and executive director of Alibaba Global Leadership Academy, pens learnings from his tenure at the global technology group and how it has impacted his own worldview and life as an entrepreneur and investor in the book: Tao of Alibaba.

More than twenty years later, Brian Wong, former longtime executive, assistant to Jack Ma, founder of the Alibaba Global Initiatives division and executive director of Alibaba Global Leadership Academy, pens learnings from his tenure at the global technology group and how it has impacted his own worldview and life as an entrepreneur and investor in the book: Tao of Alibaba.

In this call, Brian not only gives a rundown of the book, but also shares how the management ethos and principles of Alibaba have been applied and can apply to a variety of areas of leadership and life, from crisis management to corporate governance, hiring leaders to writing a book.

Timestamps and Highlights

(01:47) Tao of Alibaba: The TLDR Version;

“So the Tao of Alibaba, the book, is really, you could say it’s a story of three different parts…The third story is also one of a personal journey and how someone who was raised in Palo Alto, California, went to China, and really learned some eye-opening things about how the role of business and technology really can affect society for the better. And how eastern philosophy and western philosophy sort of mix into an organization that I think has created something quite unique. So what I always often talk about is that I had to leave Silicon Valley to appreciate Silicon Valley and what it has to offer the world, but also see how other parts of the world are contributing to this digital sort of transformation that’s impacting the rest of the world.”

The Tao of Alibaba in Action through:

(07:38) Crisis Management; “What happens in cases where you have crises or existential threats or situations where you’re very uncertain? If you’ve got this proper flow in terms of how the leader sets a vision, a mission and a vision, how the team thinks and whether or not they buy into that, whether or not they believe in that, oftentimes the organization will adapt almost instinctively to challenges.”

(11:12) Organizational Maturity; “…as a mature organization, as you grow in terms of size and scale, but also kind of administrative processes and bureaucracy, it’s important to think about how do you stay nimble…one of the things that Alibaba did in 2013, if I recall, is that they actually took what was then three major business units, and broke them up into 25 smaller ones…[Jack] felt people weren’t being given the opportunity to continue to innovate and fulfill their greatest potential because there was too much bureaucracy.”

Financial Discipline; “…we always had a saying that “money makes you stupid” because you start to get lazy and rather than really figuring out how to solve the problem, you throw money at the problem…remain really scrappy in terms of the mindset. I think that this is something that’s easily lost when you become a large corporation. So being frugal and trying to be really creative with how you spend money and use it to the fullest is an important characteristic.”

Corporate Governance; “It’s the Alibaba partners, then there’s a board of directors. The partners nominate people for that board, and also the CEO and Chairman, but the whole premise of this is that there are many tech companies that are great. And then as the founders left and the professional managers came in, one of the problems is the professional managers were really focused on kind of managing quarterly profits and earnings so they could maximize their compensation, but they weren’t thinking about the long-term wellness of an organization because they didn’t have maybe the privilege or the luxury of understanding why that company had gone through what it had gone through, why it exists.”

(17:39) Building in SEA vs China; “Alibaba started out from e-commerce, then moved to payments, then went to cloud computing, and then to logistics, and then into things like ride sharing and whatnot. What’s very interesting is that companies like Gojek started out as a ride-hailing service, motorcycles and then they went into payments, and then they went into all these other services, ecommerce and even media, like advertising. The progression of these digital economies can be different in each market. What’s most important is that they kind of focus on the needs of the market.”

(21:23) Leadership Hiring; “I think that in a market that is so nascent, like China at the time, what you need more than just world-class experience is someone who has the right mindset that is agile, adaptable…They have to know how to iterate. They have to know how to adapt and they have to be willing to put in the hard work, and not just pull out templates and say, “Let’s try this because this is what I did at my last company, or this is what the MBA course taught me.””

(25:08) Building in Bear Markets; “…in a bear market, it’s about going back to your roots and saying, “Okay, what is it that I can do that’s gonna help my customer base?” And obviously you need to help yourself as a company, but hopefully helping your customers is going to help them survive, which means they’re gonna stay loyal to you, and then in the long run, you’re gonna be building up a sustainable business.”

(27:23) Learnings from Writing a Book;

“…there are things in life that sometimes in the immediate scheme of things, you don’t always know why you’re doing it, or you ask yourself, why am I suffering so much? But again, this goes back to this mission and vision, but for you as a person, like why do you exist in this world and what is it that you want to achieve? And I think that an entrepreneur needs to ask themself that question in the same way that a book author needs to ask him or herself that question, why am I making this investment? And there needs to be a greater purpose…”

(29:39) #MinuteMasterclass: Tao of Alibaba Approach to ESG;

“In the vision statement that Alibaba has today, it’s not about how much revenue or how much profitability the company’s gonna make. Although we did have GMV targets, at one point, these weren’t part of the vision statement. The vision statement talks about jobs created. It talks about the number of SMEs that will be profitable. And the thinking behind that is if you’re helping your community, if you’re helping your customers, then you’re gonna be creating value for yourself, because you’re creating value for your constituencies or your customers.”

(32:31) #RapidFireRound;

About our guest

Brian A. Wong is a Chinese American entrepreneur and investor. He was the first American and only the fifty-second employee to join Alibaba Group, where he contributed to the company’s early globalization efforts and served as Jack Ma’s special assistant for international affairs. During his sixteen-year tenure, Wong helped expand Alibaba’s business presence in the US, Europe, India and Asia, established the Alibaba Global Initiatives (AGI) division and was the founder and executive director of the Alibaba Global Leadership Academy. Wong remains an adviser to the AGI team and regularly teaches courses on China’s digital economy and the Tao of Alibaba management principles. Wong is also founder and chairman of RADII, a digital media company.

Wong earned his bachelor’s degree from Swarthmore College, a master’s certificate from the Johns Hopkins University (SAIS)–Nanjing University Center for US and China Studies, and an MBA from the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School. He was selected as a Young Global Leader by the World Economic Forum in 2015, is a China Fellow with Aspen Institute and a member of the Aspen Global Leadership Network and is a member of the Committee of 100. He is based in Shanghai, China.

Transcript

Tao of Alibaba: The TLDR Version

Paulo J: So the Tao of Alibaba — you’ve educated a lot of people about this through the programs that you have, but I’m sure there are many folks, including myself, who only heard about it maybe a few months ago and really got to know this concept. So maybe you can kick things off by sharing with us what exactly is the Tao of Alibaba in a few lines or so.

Brian W: I’m gonna back up a bit and just kind of give a quick Cliff Notes version of what is the Tao of Alibaba from the book perspective so people understand the context. And I’ll just kind of talk a little bit about the specific management fundamental principles too. So the Tao of Alibaba, the book, is really, you could say it’s a story of three different parts.

The first is, really as an American who worked at the company for almost two decades, what was my sort of outside perspective on highlighting the enabling factors that led to the rapid rise of China’s digital economy, reflecting both the role of government and the private sector and how those two really interfaced. And I was constantly asking myself kind of how China transformed at such a fast rate given it started with so little. Its baseline was virtually nothing. And then comparing that to Silicon Valley, which is really the leader in so much of technology that we have today, how did China sort of grow so quickly? And that’s what I answer in the first part of the book.

So the second part of the book is really the secret sauce, so to speak, and here’s where I kind of get into the management principles of Alibaba. And I think this is probably most useful for entrepreneurs or even executives at large companies alike to really understand the management ethos of the organization.

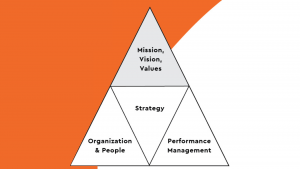

And this relates to the diagram that I lay out that at the very top, the guiding principles are the mission, vision, and values. Underneath that is really the strategy that kind of drives how to implement those mission, vision, and values. And then you’ve got the people and organization that really kind of support the implementation of the strategy. And then performance management is how you really motivate your employees. So that’s what I talk about kind of in the second part of the book.

And then the third, I would say, story is also one of a personal journey and how someone who was raised in Palo Alto, California, went to China, and really learned some eye-opening things about how the role of business and technology really can affect society for the better. And how eastern philosophy and western philosophy sort of mix into an organization that I think has created something quite unique. So what I always often talk about is I had to leave Silicon Valley to appreciate Silicon Valley and what it has to offer the world, but also see how other parts of the world are contributing to this digital sort of transformation that’s impacting the rest of the world.

Paulo J: One thing I want to say though is that the second part was actually the one — it’s a lot of concepts that are not foreign to us. Everybody knows mission, vision and values, but then giving that sort of Alibaba perspective and really talking about it from the experiences that you guys went through, both the wins and even the failures as well — it was really great to read about.

And so, you’ve taught this Tao of Alibaba, as I mentioned earlier, through the AGI, the AGLA and all these initiatives. But what made you decide that it was time to put it into a book sort of format and write about it?

Brian W: Paulo, you mentioned the AGI programs, Netpreneur, E-Founders Fellowship Program we did with you guys and we’re very grateful to Insignia for all the support.

And I realized that teaching these classes, you can maybe impact thirty, a hundred, sometimes 200 at a time. In order to really share this knowledge, I thought writing a book would be the most effective way that knowledge can be packaged very efficiently within this book and then shared with the rest of the world. And oftentimes people don’t have the time to sit through a four-week course online or come visit Hangzhou to see what’s happened and I think a book format was a very convenient way to do that.

But also I kind of reached a period in my career where I spent almost 20 years at a company. I felt like now is a good time to kind of have a milestone event where you kind of encapsulate all that and then think about how you take that knowledge and apply it in other areas.

And then the third reason I’d say I wrote the book is I’ve been kind of looking at how the dynamics of the US and China have been evolving. And I think that one of the things that concerns me most is this lack of engagement, particularly with COVID. It prevented a lot of travel, right?

And so one of the things that I realized is that the interaction between people face-to-face visiting an environment, a city, a community, really does help address people’s concerns or even creates more familiarity between people and not having that, I think has created more and more distance.

And so this book is also a way to personalize and really humanize what’s happening in China from a technology standpoint and help people to understand outside of China that the people that are running these companies, that are part of this whole phenomenon, are just like everyone else. They have the same aspirations and they’re trying to do good for their communities.

“The third story is also one of a personal journey and how someone who was raised in Palo Alto, California, went to China, and really learned some eye-opening things about how the role of business and technology really can affect society for the better. And how eastern philosophy and western philosophy sort of mix into an organization that I think has created something quite unique. So what I always often talk about is that I had to leave Silicon Valley to appreciate Silicon Valley and what it has to offer the world, but also see how other parts of the world are contributing to this digital sort of transformation that’s impacting the rest of the world.”

Tao of Alibaba in Action Part 1: Crisis Management, Organizational Maturity, Financial Discipline, and Corporate Governance

Paulo J: I really like what you said in that third point, and you really bring that to life especially with rural China talking about like the Taobao villages and all of that. Some interesting stories there, especially when Jack Ma asked you to go to the poorest village in China and see what you could learn. Let’s dive more into the book with a few more questions about that.

So one of the most interesting aspects, at least for me, was how Alibaba leveraged the Tao of Alibaba approach, as you’ve described, to navigate existential crises throughout the company’s growth. So maybe to better illustrate what you just ran through a while ago, maybe you can give one example of these components in action, like a teaser from the book.

Brian W: One of the things that I talk about, not only in that management principles structure, but also in the leadership principles — I mean there’s a saying, “leading without leading.” That’s a very Daoist principle and the book is called The Tao of Alibaba.

And the book really does try and encapsulate multiple aspects of this Daoist philosophy. One is kind of the path or the way, and so sort of a natural sort of force that directs you or a journey that you take as part of being who you are. And the second aspect is kind of being in harmony with your environment. And that’s also a dynamic of this yin-yang we talk about. And then third is this sort of embracing of contradictions.

So if you think about these three principles in terms of the Tao, what happens in cases where you have crises or existential threats or situations where you’re very uncertain? If you’ve got this proper flow in terms of how the leader sets a vision, a mission and a vision, how the team thinks and whether or not they buy into that, whether or not they believe in that, oftentimes the organization will adapt almost instinctively to challenges.

And one great example was in 2003. Before Covid, there was an outbreak called SARS. And this was something very serious in Asia in 2003. It actually affected Alibaba as a company. There was an alleged case that one of the employees had SARS and returned to Hangzhou and which led to a whole lockdown of the company and the business.

And keep in mind that was a time when WiFi was not prevalent. We didn’t have 5G. Even laptops were a luxury. And so how would an organization be able to operate if everyone needs to leave the office and stay at home? They actually kind of sealed people into their apartments for like 10 days.

It doesn’t seem like a lot now, given we’ve gone through a lot longer duration. But the technologies and everything were much different, much more rudimentary. Strangely enough, there was such a strong sense of needing to serve businesses because other businesses, our clients were affected by this, that the employees themselves instinctually took their desktop computers and they all moved them home.

They worked out of their home for that period of time. They continued to answer calls. They stepped up kind of the work that they had to do, and they even had, in some cases, their mothers and grandparents answering phones to help the clients who were all very concerned about what was happening in terms of their businesses.

So they were able to operate the business remotely without a lot of top-down leadership saying, you must do this, you must do that. But also they managed to launch a new company at that time called Taobao. And we all know what Taobao is today. It’s the largest retail marketplace in the world, Taobao and Tmall.

But that all happened during a crisis period. So I think that speaks volumes about how, the motivation behind the employees was so strong in terms of needing to serve and wanting to fulfill a mission that even amidst this time, they were able to do great things.

Paulo J: Really inspiring, especially since that all happened more than 20 years ago. And actually, that whole story is actually counterintuitive in itself in that to be flexible, you need to have strong foundations to be able to adapt to different crises. You need to have those first principles and be able to go back to why you’re doing things.

Another thing that the book talks about, and I think it’s pretty relevant to today, especially now in Southeast Asia, where a lot of startups are facing this bear market, but also a lot of them are facing growing pains, right? They need to think about things like corporate governance, financial discipline, and all of that. So what can leaders, especially of these fast-growing startups, learn from the book, especially when it comes to bringing structure into their company and discipline and all of that?

Brian W: The first thing to say is that no matter how big a company, it will always go through development cycles. And that’s been true for Alibaba. If you think about it, for 23 years, it has grown into what it is today from 18 people now to about 250,000 employees and now the highest GMV of any e-commerce company in the world. But it’s done this way in iterations. It’s constantly recreating itself.

And so as a mature organization, as you grow in terms of size and scale, but also kind of administrative processes and bureaucracy, it’s important to think about how you stay nimble. And one of the biggest challenges I’ve seen is that as you become bigger, you become much more of a target, and then the smaller, more agile startups can start chomping at your heels and biting off little bits and you become much less flexible.

So one of the things that Alibaba did in 2013, if I recall, is that they actually took what was then three major business units, and broke them up into 25 smaller ones, because I think Jack felt like the company was becoming too slow. He felt people weren’t being given the opportunity to continue to innovate and fulfill their greatest potential because there was too much bureaucracy.

Every decision that you wanted to make had to go through two or three or four people, whereas if you’re in a startup, oftentimes you just have a conversation with you and the founder, or the founder and his lieutenants, and then boom, it’s done. So that I think from a maturing organization standpoint, in addition to the things you talked about, kind of building up an infrastructure that allows for corporate governance in these things, with proper financial management, you still need to stay nimble. And so I think it’s important to think of it as a cycle as opposed to just a one-way, linear movement.

In terms of financial discipline, I would say that as you become bigger and you raise more money, we always had a saying that “money makes you stupid” because you start to get lazy and rather than really figuring out how to solve the problem, you throw money at the problem. And I don’t know how many times I heard people say, “Oh, I don’t have enough headcount, or I can’t do this ’cause I don’t have these people.” Well, when you started the company, you didn’t have those people and you had to figure out how to do it. And oftentimes you came up with innovative, creative solutions.

And I think that is also an important thing — to remain really scrappy in terms of the mindset. I think that this is something that’s easily lost when you become a large corporation. So being frugal and trying to be really creative with how you spend money and use it to the fullest is an important characteristic.

And then when you finally talk about corporate governance, you need to ensure proper transparency, checks and balances. As you become larger, things are harder to watch and monitor. So you have to have those systems in place. But I also think succession planning is very important because as a founder, you have to realize that you’re not gonna be at the company forever, and you need to enable others to grow and take on responsibility.

And this is one of the hardest things for any founder or entrepreneur, to give up control to others in the company because you feel like you know it all or you’re just paranoid that the wrong decisions are gonna be made. And I have a startup now and I’m probably the worst culprit of this, even though I talk about this in the book, it’s very much like a psychological thing.

And if you’re good at doing something because you’re used to controlling it, how then do you justify or feel okay about giving others that space to try it? And that’s something that Jack was very good at because as a teacher, he was used to empowering others and trusting them. And I think that when it comes to corporate governance, you have to think about all these different aspects.

Paulo J: To that third point on corporate governance, I really found the whole concept of the Alibaba partnership really interesting. Maybe you could just give a brief sort of description of how that worked.

Brian W: Of course. Jack realized that at some point, and he had actually been preparing for his retirement for almost 10 years. He said, “I don’t want to die in an office. I want to die on a beach,” so I need to prepare for my transition. And so what he did over that time was identified 30-something partners — I think it’s 38 now — whom he felt were really the protectors of the company values, the mission and the vision, and this partnership is really a group that is responsible for ensuring the longevity of the organization.

Essentially, he took himself and then hoped that these 30-something partners would share the same values, but also could carry the company forward when he was not there. He didn’t want that once he was gone, all of that would be lost. And so today they make decisions in terms of board appointments, CEO nominations, and also maintaining the mission and vision, and values of the organization.

And many of them are co-founders from the original 18. But there are also many who are executives who joined afterward, but are equally passionate about the company and values.

Paulo J: But just to clarify, these partners aren’t the board itself, right? They’re sort of just like a subgroup within the…

Brian W: Exactly. It’s the Alibaba partners, then there’s a board of directors. The partners nominate people for that board, and also the CEO and Chairman, but the whole premise of this is that there are many tech companies that are great.

And then as the founders left and the professional managers came in, one of the problems is the professional managers were really focused on kind of managing quarterly profits and earnings so they could maximize their compensation, but they weren’t thinking about the long-term wellness of an organization because they didn’t have maybe the privilege or the luxury of understanding why that company had gone through what it had gone through, why it exists. And they didn’t have the incentive to try and address those longer-term issues, because if they didn’t manage the quarterly earnings, they might not have a job.

“It’s the Alibaba partners, then there’s a board of directors. The partners nominate people for that board, and also the CEO and Chairman, but the whole premise of this is that there are many tech companies that are great. And then as the founders left and the professional managers came in, one of the problems is the professional managers were really focused on kind of managing quarterly profits and earnings so they could maximize their compensation, but they weren’t thinking about the long-term wellness of an organization because they didn’t have maybe the privilege or the luxury of understanding why that company had gone through what it had gone through, why it exists.”

Tao of Alibaba in Action Part 2: Learnings from China to SEA, Leadership Hiring, Building in Bear Markets

Paulo J: So the partners provide that balance to the intuitive way of how professional managers might think coming into the company.

Moving into the Southeast Asia angle that you write about in the book, we’ve talked about AGLA and AGI a while ago, and it’s all about scaling up that whole teacher philosophy and teacher sort of mindset that Jack had, but I was curious to know, what did Alibaba learn on the flip side? What did you guys learn from all these sharings that you did with Southeast Asian entrepreneurs?

Brian W: First of all, I wanna say that I’m really impressed with what Insignia does in terms of its learning and teaching. I know you guys have a pretty robust program now, and I think that being an entrepreneur is the process of constantly learning. And so by enabling that also as a VC you have to be constantly in the market and learning. I think you guys do a great job of facilitating that.

With the AGLA program, Alibaba Global Leadership Academy, and AGI (Alibaba Global Initiatives), both those programs we created were really intended to share Alibaba knowledge from the last 20 years.

But I would say on the flip side, we learned from each of these entrepreneurs. AGI continues to run its training and just today I was contacting some people at Lazada and sharing some of the progress that the entrepreneurs from one of the E-Founders classes have made that will be very beneficial to Lazada itself.

So I’d say that one of the things that I learned and we’re very impressed with in terms of the local companies is how they’ve taken the principles of some of the digital economy developments in China and then applied those in a more localized way to the Southeast Asian market.

Also, the progression by which these companies have grown — I mean, some of now the bellwether digital companies like Gojek, Grab — Alibaba started out from e-commerce, then moved to payments, then went to cloud computing, and then to logistics, and then into things like ride sharing and whatnot.

What’s very interesting is that companies like Gojek started out as a ride-hailing service, motorcycles and then they went into payments, and then they went into all these other services, ecommerce and even media, like advertising. The progression of these digital economies can be different in each market.

What’s most important is that they kind of focus on the needs of the market. And I think one of the unique things about Indonesia is its traffic and how you don’t take a car. You’re gonna get a lot faster if you’re on a motorcycle. But who knew that that whole business would open up? Completely different opportunities in terms of — like I talked about the logistics, shopping, food delivery, et cetera, and payments. It’s really interesting.

Another area that I think is interesting is how these companies have adopted technology to their own local markets. In the fisheries industry, there’s a company called E-Fishery, which I think is doing very well in Indonesia, but it’s growing to other markets. It’s even looking at expanding into China. Who would’ve thought that you could apply e-commerce and FinTech to the fisheries market? That’s something that I think really was pioneered in Southeast Asia.

And so there are other companies that have done similar things that I think are really for us, or for Alibaba, and for me personally, eye-opening. And I was really inspired by a company that is an insurance tech, a company called PolicyStreet, which really took this principle as enabling kind of the bottom 40 in society, and then applying the technology to create insurance products for people that are in the gig economy, for those who are doing street food vendors, and I think that that is also an innovation that’s happened locally but echoing the kinds of things that have happened in China.

So to me, these are all great stories, but it also shows that what you call — indigenous or local innovation — is very rich in terms of how it evolves and takes its own path.

Paulo J: I’d like to shift gears again and talk about another interesting aspect of the book, for me, which was the conversations that Jack had brought in people to the company. One that comes to mind right now is actually the Alipay conversation where Jack was like, “Do you know anything about financial technology?” Then the guy was like, “No.” Then Jack went, “Okay. You’re the perfect guy.” So what can startup leaders learn from these conversations, both leveraging internal talent as well as attracting top talent like yourself and Joe Tsai to take their business to the next level.

Brian W: Well I would definitely not put myself on the level of Joe Tsai ’cause he’s another level. But I’m honored that you would say I’m top talent. But your point is, how do you sort of balance that internal versus external hire?

I would say that this is a topic I thought about a lot because I saw a lot of success and a lot of failures in this area during my time at the company. I think that certain kinds of talent, like expert talent, world-class talent, are very important in certain areas. You mentioned Joe. Joe was our first CFO and he’s also the finance, legal, and kind of governance head of the organization. All of the kind of structures and the financing and everything really kind of was led by him. And without someone with his skills, I think the company would not have been able to raise the money. It would not have been able to attract the investors it did. And that I think is where you want world-class talent.

In terms of things like technology, I think there’s also that element where you want someone who at least knows what’s out there in the world, in the market, and can identify what is the most appropriate technology for the organization. I would make one caveat to that though, and say that not every company needs world-class technology talent from day one. I think that a technology leader should be someone who knows what’s available but then is willing and flexible to select what is most appropriate for the market at that time.

And fortunately we were able to find that combination, even though we had one of the best technologists from Silicon Valley. His name was John Wu. He invented the Yahoo search engine. We were not a technology company from the start. We were much more of a kind of sales organization building websites.

He was able to at least adapt that as needed for all other areas like sales, product and marketing. I think that in a market that is so nascent, like China at the time, what you need more than just world-class experience is someone who has the right mindset that is agile, and adaptable, but also understands the market needs, and is willing, frankly, to put in the time to make it work.

They have to know how to iterate. They have to know how to adapt and they have to be willing to put in the hard work, and not just pull out templates and say, “Let’s try this because this is what I did at my last company, or this is what the MBA course taught me.”

If you look at the company as a whole, you had some world-class experts like Joe, like Savio, who also was the COO, right? And what he brought was management principles inspired by GE. But again, he had the humility to say, “Okay, how do we make this work, with this team and this market?

But then you had the rest of the leaders, some of the people who have become great leaders of the group. Jack himself had no technology experience, but he’s the founder of Alibaba Group. He was an English teacher. Taobao was started by a guy named Toto Sun. He was my first boss.

He was more of an internet guy. He had no retail experience, but he started Taobao. Alipay, which you mentioned, was started by Jonathan Lu, who had come from a hotel manager experience, and then Cainiao was started by Judy Tong. She was the CEO and founder and she was the company secretary at Alibaba and worked up the ranks. These are all examples of what they call rookies who became great leaders.

Paulo J: As I mentioned at the very start that this book definitely stands out amidst all the sort of media doom and gloom in the tech markets and it is a bear market and all of that. What would you say is something that businesses can learn from Alibaba when it comes to building in a bear market, especially emerging markets, which tend to be most impacted during things like a global recession?

Brian W: What Jack used to always say is when the sun is out, it’s time to fix your roof because when it starts to rain, it’s already too late. You can also maybe reference the common phrase, “only the paranoid survive.”

So I felt that, and this also goes to kind of the whole naysayer or contrarian view whenever people were celebrating and the economy is really good, Jack’s like, “now you gotta be very careful.” And so what I think it requires is for an entrepreneur to always be thinking about what are the risks that we need to plan for. And I think that will ensure that you’re kind of well situated for anything that comes at you and you’re gonna be able to adapt when that happens.

The other thing I would say is, in a bear market, it’s about going back to your roots and saying, “Okay, what is it that I can do that’s gonna help my customer base?” And obviously you need to help yourself as a company, but hopefully helping your customers is going to help them survive, which then means they’re gonna stay loyal to you, and then in the long run, you’re gonna be building up a sustainable business. Those two things, I would say, are quite important.

If I give an example, in 2008, when there was a financial crisis, what we did at that time was actually reduce our prices to help the companies survive. And ironically, what that did was actually increase sales beyond what we would’ve expected. It also built loyalty for our customers.

During COVID, what we did is we started to deploy services that helped the mom-and-pop shops get online because with COVID, there was no foot traffic. So we repurposed certain platforms and helped these small shop owners get online, but also repurposed our platform to help those mom-and-pop shops or restaurants who had wait staff that was not being utilized to then help them become delivery people. All those things we were able to do in response to the challenges. And as a result, this kind of helped not only ourselves, but also helped our customers.

“The other thing I would say is, in a bear market, it’s about going back to your roots and saying, “Okay, what is it that I can do that’s gonna help my customer base?” And obviously you need to help yourself as a company, but hopefully helping your customers is going to help them survive, which then means they’re gonna stay loyal to you, and then in the long run, you’re gonna be building up a sustainable business. Those two things, I would say, are quite important.”

Learnings from Writing Tao of Alibaba

Paulo J: I’d like to actually also ask about your whole writing experience, putting this book together, given that you went through these experiences yourself and you know, have already been sharing these lessons a beat not in a, in a book format. is there something new that you actually learned and throughout the process of writing this book, like something that you didn’t realize before, as you were putting this together?

Brian W: I learned a lot of things. One is that writing a book is a lot harder than I expected. It’s actually quite similar to starting a business.

It’s lonely. It takes a long time and you’re constantly asking yourself, why are you doing it? Because no one else seems to care. The good thing, however, is that once it’s done, you feel very proud of the achievement. It’s something that you feel represents something important in your life, but also has the potential to help others, and hopefully will last, for a period of time.

All that is to say that there are things in life that sometimes in the immediate scheme of things, you don’t always know why you’re doing it, or you ask yourself, why am I suffering so much? But again, this goes back to this mission and vision, but for you as a person, like why do you exist in this world and what is it that you want to achieve?

And I think that an entrepreneur needs to ask themself that question in the same way that a book author needs to ask him or herself that question, why am I making this investment? And there needs to be a greater purpose because every day I would sit down in front of the computer from 9:00 PM till 12:00 AM and then in the morning from like, 7:30 AM to 8:00 AM.

It was painful, when you have writer’s block, you’re like, “Geez, this is totally ridiculous.” And it cuts into your social life. It’s like one long homework assignment that doesn’t go away for two years. Imagine that. But you’re like, “I gotta do this. I gotta do this because I think it’s important. I wanna share this with the entrepreneurs. If I don’t do it, I’m gonna regret it.” And I want to look back, say in 30, 40 years and say, “okay, this is something I contributed to the community.”

“…there are things in life that sometimes in the immediate scheme of things, you don’t always know why you’re doing it, or you ask yourself, why am I suffering so much? But again, this goes back to this mission and vision, but for you as a person, like why do you exist in this world and what is it that you want to achieve? And I think that an entrepreneur needs to ask themself that question in the same way that a book author needs to ask him or herself that question, why am I making this investment? And there needs to be a greater purpose…”

#MinuteMasterclass: Tao of Alibaba Approach to ESG

Paulo J: There’s a lot of talk about ESG and sustainability these days. What can businesses learn from Alibaba, in terms of one, measuring and two, monitoring sustainable impact? What frameworks do you guys use when it comes to that?

Brian W: The funny thing is that ESGs as a term, really came into existence just a few years ago, but since the start of Alibaba, it has been something that before we even knew what they were, we were doing it. And I actually personally witnessed this, when we were going around, after the IPO with Jack and people would say, “You’re doing this great stuff for the environment. You’re doing this great stuff for women’s empowerment.”

And Jack’s like, “Oh, really? That’s kind of what we already do.” because he always looked at the company as an ecosystem. We brought in experts from the Nature Conservancy that talked about biological ecosystems and the importance of how things fit together. We’ve been very proud of the leaders that we have in the company, over 33% of the senior management happened to be women and 50% of the staff are women in a tech company. And so that was something that we just felt was normal and natural, but people started pointing it out.

And I think that if anything, this ESG and then the governance part was really about survival, right? We talked about the Alibaba partnership, but these things were done because I think they were motivators to Jack and the team and all of us who joined the company for the work we did. And if you look at the goals and objectives, say in the vision statement that they have today, it’s not about how much revenue or how much profitability the company’s gonna make.

Although we did have GMV targets, at one point, they weren’t the vision statement. The vision statement talks about jobs created. It talks about the number of SMEs that will be profitable. And the thinking behind that is if you’re helping your community, if you’re helping your customers, then you’re gonna be creating value for yourself, because you’re creating value for your constituencies or your customers.

They also have programs like this Ant forest program which essentially uses technology to influence people’s behavior to be more conscious of the environment. And also through a personal carbon ledger, they can take those carbon credits and plant trees. Over 450 million trees I think have been planted in China, thanks to that program. That is all just part of a lot of this is bottom-up DNA, that the employees think of things also.

“In the vision statement that Alibaba has today, it’s not about how much revenue or how much profitability the company’s gonna make. Although we did have GMV targets, at one point, these weren’t part of the vision statement. The vision statement talks about jobs created. It talks about the number of SMEs that will be profitable. And the thinking behind that is if you’re helping your community, if you’re helping your customers, then you’re gonna be creating value for yourself, because you’re creating value for your constituencies or your customers.”

#RapidFireRound

What digital technology or innovation excites you the most today?

Brian W: I would say generative AI. I’m not an expert in all this. I know there are a lot of different ones emerging, but obviously ChatGPT is the one everyone’s talking about. But I’m excited about this, not because I think it’s all good per se. I think there are a lot of risks because people don’t know how to parse the information in terms of accuracy and know where this information comes from. But I do think that in other ways, it’s going to make people more productive.

And it’s going to have major ramifications on how we as a society do our work and interact and think about things. And so I think that anything of this magnitude of potential impact needs to be understood. And I’m particularly uncomfortable when anything to me is a black box, and so I don’t like to just blindly follow stuff, even though I do use the Google search engine. I don’t know what’s in the algorithm, but I do know what the principles are behind that.

And so I think it’s very dangerous if you kind of just type something in and accept it at face value. At least at Google, you have sources that you know where it comes from. I think we need to be, with AI, just really careful, but at the same time, be excited about what the possibilities are.

If you were given the resources to produce a Netflix series, what would it be about?

Brian W: I want to do this. Maybe someone in your audience will help work with me and we can co-fund it. I wanna do a historical fiction film about Georgetown Penang from the late 1700s to the early 1900s. And I think that this is a fascinating place because it’s this melting pot of a mixture of cultures. And it was a time of globalization. It was a time of historical significance. Sun Yat Sen went down there as a hideout for the Chinese revolution. It was where a British general who lost the war against American independence, Cornwallis, had something named after him. And it’s also where you have this blend of all these rich cultures: Indian, Malay, British, Jewish, Chinese, Armenian, and more.

Looking back now, what is a skill, a soft skill or hard skill, that you believe you should have learned back in your time as a student at university or even way earlier?

Brian W: I just wish I had more appreciation for math, physics, and computer science. I mean, I was curious about all of them, but I didn’t do enough. I really respect people like Elon Musk, for whom it kind of is intuitive, right? And then also, I wish I had studied more music. I was a musician, but I just wish I had mastered it to a level where I could kind of compose more.And the reason why I like these hard sciences and kind of the arts altogether in one is because I think that with the left brain, right brain, you want to develop both because the mixture of those then creates amazing possibilities that hopefully are things that generative AI cannot do.

What’s your most memorable trip to Southeast Asia?

Brian W: Angkor Wat 2001. It was very new. There wasn’t a single five-star hotel, but we got to explore the temples and I think what Angkor Wat showed me was that there were great civilizations that existed in the past that we are maybe not always aware of. That was a mixture of Hinduism and Buddhism, but also Angkor Wat is the largest kind of religious structure in the world, and it represented an earthly model of the cosmos. A miniature replication of the world built in stone and there are a lot of kinds of cosmology principles. Even the way the sun when it comes through and it shines into the structures has a logic behind it. I think it’s just an amazing way to show that we don’t have everything figured out. There are people that had things figured out way, way back and maybe we have forgotten these systems and it probably requires some revisiting of history.

What’s your favorite activity to de-stress?

Brian W: I like deep sea fishing or walking along the beach at sunset. I’m very much a water person.

Paulo J: What’s the biggest catch you’ve had?

Brian W: I’ve caught a sailfish that was like five feet long. I’ve caught many in Costa Rica. It’s really awesome, but even when you’re not catching anything, just sitting out on the water is really relaxing.

Anything you’ve read or taken up recently you’d like to recommend to our listeners

Brian W: Tao of Alibaba. Hands down. I mean, after you read the Tao of Alibaba, maybe, Tiny Habits by BJ Fogg. I’m getting into that, and I’m trying to think about how you can use technology to actually drive behavioral change through tiny habits.

What’s the biggest thing you’ve done for love, if you don’t mind sharing?

Brian W: I could tell you some cheesy like proposal thing, which I did in front of 400 people. But the really heartfelt one, and this is a little bit more serious, was last 2021, when my mother, unfortunately, passed away. But it was also the time when my second daughter was born. So when I think about — and that all happened within one month. So I had to leave China at a time when there were COVID travel restrictions, figure out how to get out of China, go to the US, had to tend to my mother who passed away, with us all, my father and my brother next to her, and we had to take care of all the arrangements.

Then I had to fly back to China to tend to my wife who was giving birth, who ended up giving birth early, and had to fly herself down from Shanghai to Hong Kong to give birth. Then I had to go down to Macau to meet her where she was quarantined to come back to China and that whole logistical nightmare — if you think about it, just one of those events was enough to stress someone out.

I did that all within like three weeks, and surprisingly, my mind was so clear, and I was not stressed. It was just focused on getting things done. And to me, that fits — you could say it’s the power of love or it’s the power of just the human will to power through things because they were obviously the most important people in my life and I look back on that and I’m just amazed that we were able to achieve all that in that amount of time.

Paulo J: Thanks for sharing that really heartfelt story of the human spirit and on that note, thanks so much Brian for coming on the show. If you folks wanna check out the Tao of Alibaba, we’re leaving a link in the podcast description.