This article was co-authored with Paulo Joquino.

If you’re an unstoppable startup founder building in crypto and web 3.0 in Southeast Asia, or in any sector in the Philippines, we’d love to meet you! Reach me at chelsey@insignia.vc or Chelsey Pua on Linkedin.

Highlights

- From the investor perspective, the presence of regulatory clarity does not just also build confidence in the market but also sets up a framework from which to filter the likely winners from the rest (i.e. the ones who secure licenses first).

- All in all, the Philippines’ TAM does not have to be limited to its digital or internet population, or even actual geographic population.

- The clear government direction, strong ecosystem support, and abundance of venture funding and emerging success stories together make a strong case for the return of Filipino talent specifically to the tech scene within the country.

- The importance of this diversification in conglomerate approaches to investing in startups means that regional and global investors no longer have to confine themselves to entering in later stages or be worried as much about getting boxed out of deals.

- Developing economies will develop startups more effectively if they pay more attention to creating positive regulation, increased digitization, and conducive overall business environment rather than providing grants and incentives themselves.

Like many economies in the region, 2021 has been a milestone year for the Philippines as its startup ecosystem racked up record fundraising headlines with the likes of Kumu (B and C round), Yield Guild Games (US$4.6M), PDAX (US$12M Pre-B), and even our own portfolio company tonik (US$17M Pre-B), reflecting greater interest in fuelling the clamor around its digital economy — the fastest growing in the region, according to this year’s SEA E-conomy report, with 93% growth and 12 million new digital citizens.

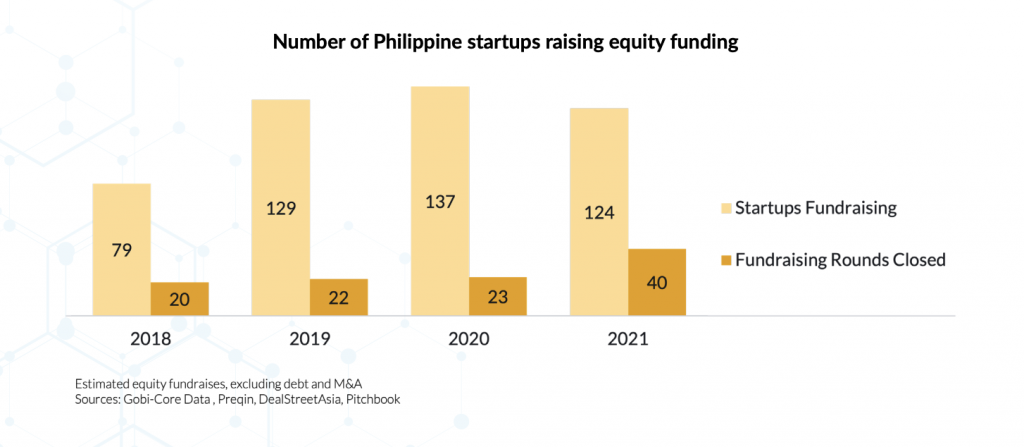

Even with the macro tailwinds pointing towards more opportunity for startups to tap into, and there have been more startups founded in the ecosystem than ever before, the path to venture-backed scaling remains rocky. The Philippine Startup Ecosystem Report by the Gobi Core Fund highlights the disparity between the demand for capital and the amount of funding startups are able to actually raise, with 15-30% conversion in the past four years.

Disparity between startup fundraising and actual investments closed year on year, as documented by the Gobi Core Fund report

This challenge has its roots in persistent infrastructure issues, the relatively smaller pool of tech talent (who are willing to work for startups), and the even smaller pool of capital — all necessary to scale. The tides are changing, however, and key to creating an inflection point for the ecosystem is having a great story to come out of the ecosystem.

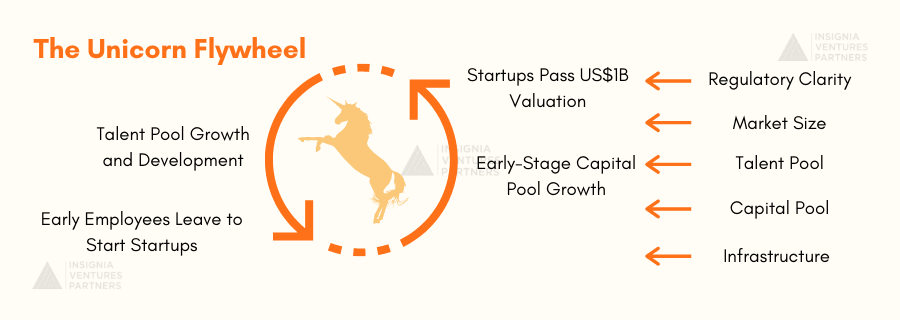

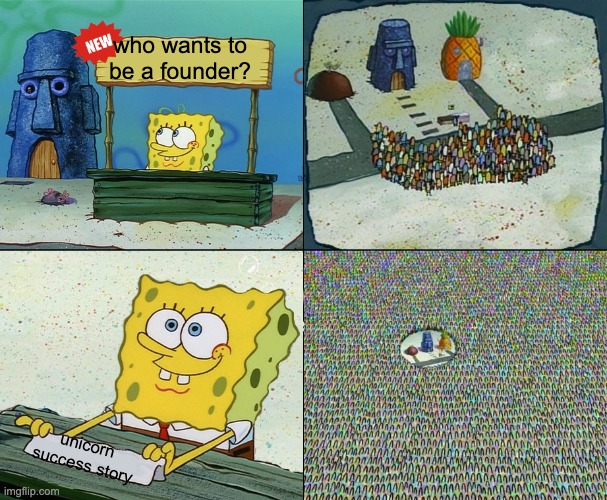

According to Gentree Fund Vice President Mark Sng, whom we had the pleasure of speaking with on our podcast, that story will be the Philippines’ first generation of unicorns. He likens it to how the first generation of unicorns in Indonesia kick-started a flywheel of startup creation and scaling that paid off dividends for the ecosystem — incentivizing founders, creating that bandwagon for investors, and attracting talent.

“I’m very excited for the next generation of, as a16z calls it, “elephants” to come up in the Philippines. The kind of way Indonesia developed was that you had the first wave of unicorns like Gojek, Tokopedia, Bukalapak. All these players came up, and then they spawned other players after them, because it showed an example that you can actually come back and do this.

You can do this exciting thing in the Philippines. People like examples, and we are about to see our first company that could be used as a strong example for people to rally around and say, “Look, this is doable in the Philippines. We can actually create a unicorn company in the Philippines and create life-changing value for everyone in the economy that consumes our product, but at the same time as well, really make strong returns as founders as well.” So this is actually worth doing, because it’s life-changing money that you make as a founder. It’s a life-changing experience that you have.

But the effect of that as well is that the people that you bring into your organization would then spawn a thousand ships. And they’re doing their own things because they learn the best practices. You are able to then convey that into the next startup. And the hyper-growth experience of double-digit growth every single month that is always expected from you carries through into your new startup as well, because you have that same sort of expectation that “I need to do this.”

Product managers who come up from that sort of hyper-growth organization behave in a very different way because they expect and they know how to scale the product in the hyper-growth format as well. That’s where the unique nature of having the first generation to build around after that becomes very important, and I think we are just about to see that in the Philippines slowly developed. So that’s why it’s so exciting for the next five years.”

With proven pathways to scale sustainable billion-dollar business models and even exit, the mass of talent and capital flowing into the ecosystem and creative value will increase. But this relationship between unicorn creation and the talent and capital influx does not exist in a vacuum. It’s important for investors and founders to understand what are the forces that have been driving this momentum unique to the country’s history and culture, especially over the past year, and in what direction they are driving the Philippines’ startup ecosystem. These forces are also tied to the challenges founders in the country have faced in scaling or even launching in the market.

This article tackles five forces and misconceptions those unfamiliar with the ecosystem will have about them:

- Regulatory Clarity: With an experimental approach the Philippines has been making larger strides than its neighbors in regulation and government support especially in fintech and for pre-seed, seed startups.

- Market Size: The TAM goes beyond digitally-savvy Filipinos and Filipinos in the Philippines. There’s a whole world of Filipinos to reach with the right business model and GTM strategy.

- Talent Pool: A confluence of the pandemic, greater cross-border collaboration, and success stories are changing the narrative of what it means to be a venture-backed startup founder in the Philippines.

- Capital Pool: Conglomerates that have historically been dominating the funding pool are switching up their strategy to be more collaborative.

- Infrastructure: Infrastructure (digital, political and socio-economic) gaps cannot be ignored in the development of the Philippine’s startup ecosystem.

License to Disrupt: The Advantage of Experimental Approach to Regulation

Regulation forms a foundational part for any market or ecosystem to develop. It can create a safety net for startups to disrupt old models and generates assurance for investors that the gatekeepers of the market are on the same page. While in terms of producing venture-backed startups, Philippines is behind the likes of Singapore and Indonesia, and even Vietnam, the country has already made strides in the foundation of regulatory clarity that founders and investors need to operate in the market, especially when it comes to fintech sandboxes and licenses.

Mark Sng highlights this progress on the podcast. “The industry with the most clarity I think is the FinTech industry in the Philippines. From very early on, even in 2005, the OPS (Operators of Payment Systems) licenses started being produced [and] developed as a policy framework. You have the FX (Foreign Exchange) license, [and] now the EMI (Electronic Money Issuer) license. Those are the three main licenses of FinTech.

And then now you have the digital banking license that’s been launched that allows you to not even have to open the branch and be able to launch a bank. I think the clarity there that the BSP has been providing is actually very significant and that has actually led to very strong investor interest in FinTech in the Philippines…And I think that the development there and the investor interest is because clarity has been provided and it’s because the regulatory framework is very clear.

Not every industry obviously needs regulation; you’re not gonna evaluate every single industry. For those that need, I think like insurtech, for instance, there’s a sandbox right now, which is really helpful for HMOs to develop out of or TPAs to develop. I think the insurtech industry has gone through that improvement in terms of clarity. There’ll be more industries that have impediments that get lifted in that sense.”

So the early availability of these licenses, sandboxes, and even innovation offices (the local SEC set up a Fintech Innovation Office this year) has played a significant role in driving investor interest in the Philippines’ fintech sector, which, combined with the participation of the large conglomerates in driving payments adoption and the massive GDP potential of fintech has contributed to much of the fundraising in the country.

In the case of the Philippines’ (and Southeast Asia’s) first digital bank tonik, Greg and his leadership team were able to make early headway into the market by working closely with the country’s central bank. They gained the regulators’ trust and confidence to get first a rural bank license to operate within a sandbox experience. The central bank would then use that collaboration to figure out how to roll out the actual digital bank license, which tonik would then have better chances of securing because they had gone through the sandbox and built that relationship with the regulator.

Greg shared this story on our podcast with him last year. “I think the regulators around the region differ hugely. So we were very lucky to find them a great partner in BSP — Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas. The central bank in the Philippines is very active and forward-looking in how they think about digital and how to use digital to solve their massive financial inclusion problem of 70% of Filipinos outside of the banking system, so they’re willing to experiment and they basically told us a year and a half ago when we first came to them.

They said, “Guys we like what you are trying to do. We like your team’s credentials. Why don’t you apply for a rural bank license and we’ll enable you to operate a digital bank on the basis of that license. We will learn through that sandbox experience, what the digital bank license proper needs to look like and then we’ll be able to advise the parliament on how to draft up legislation. And then ultimately we’ll look to convert you to that proper digital bank license.” Now that’s a very different approach than the regulators would take in Indonesia or in Vietnam. So I think what’s holding back the real evolution of digital banking around the region is very much on the regulatory side, more than anything.”

According to Greg this kind of conversation that happened with tonik and the BSP was endemic to the regulatory approach of the country when it comes to financial inclusion. The Philippines was willing to take a more experimental and iterative approach to developing its regulations compared to its neighboring economies in the region.

He adds on the podcast, “It’s something endemic to the Philippines. I think it just happened to be that the Filipino regulator is very forward-looking in using digital for financial inclusion. Philippines is the country with one of the biggest financial inclusion issues in Asia with 70% of the Filipinos being outside of the bank system and their regulator takes a much more aggressive and active approach to experimenting and letting the market kind of help them figure out what the regulation needs to look like, which I think is very progressive and very helpful because if you look for example at how Singapore went about its digital bank place versus how BSP is doing it.

So Singapore went about it in a very rigid way. They hired 20 PhDs that spent two years drafting volumes and volumes of a book called Digital Bank Regulation. And then they put it out and said, “Okay, we’re putting it out for tender now, and here are all the requirements and good luck you people, hope some of you can fit into this very narrow box that we’ve defined with a very, very high capital requirement and other limitations and regulation.” That’s probably fine for the first stage. But I think the people that will be going into that will need to have an extremely high-risk appetite because it will be very hard to make money for them.

The Filipino regulator said, “You know what? We don’t have that 20 volume book, but we’re willing to run an experiment, create a sandbox, and then see what kind of books we need to create in order for it to [fly].” And that’s why you see, for example, in the Philippines, you have a couple of very big wallets GCash, Paymaya, Coins which is now part of Go-Jek. Grab is now aggressively expanding its wallet there as well.

So these wallets are doing some extremely innovative stuff. That is not really that popular in other parts of the region, but it’s because they’re finding a very open and helpful regulator. It’s been a real pleasure working with the BSP for us. And we’re looking forward to continuing to work with them, to solve the financial inclusion problem in the Philippines.”

Crypto regulation in the country has been molded in much the same way. Despite the Philippines being the third-largest country for remittance inflows, contributing over 8% of the Philippine GDP, financial infrastructure has not been built for cross-border transactions. This gap, on top of the general lack of access to banking services among a young and tech-savvy population, fueled the emergence of an active crypto community in the country.

The Philippine authorities had again a very experimental response. As early as February 2017, the BSP released its Guidelines for Virtual Currency Exchanges, and by November 2017, the SEC started regulating digital currencies by treating them as securities. Together with subsequent rules on virtual assets and virtual asset providers, these served as models that neighbors like Thailand eventually adopted. This came to pass when the rest of the region’s authorities were reining in the global boom of cryptocurrency trading.

The Philippines’ regulatory clarity when it comes to fintech has been paying off in terms of attracting founders like Greg and global marquee investors into the market. From the investor perspective, the presence of regulatory clarity does not just also build confidence in the market but also sets up a framework from which to filter the likely winners from the rest (i.e. the ones who secure licenses first).

While these regulatory developments will already contribute to enabling more businesses to use fintech applications to support their digital products and solutions, it will also be needle-moving for the ecosystem to have other regulated sectors to open up to digital-first players as well. This is not just about setting policies and creating licenses to filter players but also co-investing with the private sector (e.g. Philippine Startup Fund) and setting up resources (e.g. QBO Innovation Hub) to support startups as they get off the ground and scale.

Key Takeaways for Founders and Investors

- Licenses (and by extension strong regulatory relationships) are an important go-to-market that creates significant competitive advantage especially in financial services.

- The Philippines has been more proactive and experimental in making strides in fintech-related regulations compared to other SEA markets.

- Regulation is not just about licenses and policies but also funds and resources available to startups throughout various stages of growth and across various industries.

TAM is not what it seems: Thinking Globally and Remotely

Apart from navigating regulation, founders in the Philippines have also long grappled with selling the Philippines as a growth market to regional or global investors. As we’ve mentioned however, the winds are blowing in a more favorable direction with GDP growth this year beating estimates despite (or even because of) lockdowns, with increased household spending. According to Mark, the angle to look at economic growth is to sell ubiquity and how solutions can generate flows that get “levied” back into the economy.

He cites fintech as a prime example of a sector that has driven investor interest by its potential to tap into the entire GDP growth of the Philippines. “Now a lot of the investor interest is in FinTech actually, [because] you’re tapping into the entire GDP growth of the country. It’s so wide ranging. It touches every part [and] every facet of your life, because you’re transacting and making transactions. Even in lending, lending is levied back on the economy, because you’re actually lending to provide growth to the economy. So it’s levied back in the economy.”

In some cases, the market opportunity may be right in front of one’s nose, but in other cases, having the right business model approach and go-to-market strategy can unlock new markets.

In the case of digital banking, Greg points out on the podcast that the Philippines, as an emerging market, needed an asset-liability approach to building a profitable and sustainable digital banking proposition compared to the transaction-based approaches taken by neobank players in Europe or the US.

This business model, combined with a digital-only go-to-market, created a dent in the existing bank infrastructure landscape, which became all the more relevant amidst the pandemic, and attracted millions of underserved middle class Filipinos, who additionally are majority in their twenties and digitally-savvy.

Greg compares the Philippines’ and emerging markets’ digital banking opportunity versus other markets. “So the digital banking underlying market dynamics are very, very favourable in pretty much all of the emerging Southeast Asian countries, you know, Indonesia, Vietnam, Philippines, Myanmar, Cambodia, Laos. All of these countries present amazing opportunities. I would say Malaysia and Thailand, a little less, because they’re much more evolved and the banks there already present to the consumer are pretty decent propositions. So I’m less excited about digital banking there or in Singapore for that matter, which is a very, very highly penetrated banking market. But I think in order to launch a proper monetizable digital bank proposition in an emerging market, as I said, you need to go for an asset-liability strategy.

And that means taking in deposits and making consumer loans. Now, European neobanks and US neobanks have executed their business in partnership with existing regulated bank entities. And when you’re doing current account business, so purely transactional business, then that’s not that difficult to do. You can partner up with a bank, and especially if your bank is pretty sophisticated. They’re like a normal European or many US banks.

Now, in Southeast Asia, that is a problem. It goes first of all, in places like the Philippines or Indonesia, the existing bank layers are very, very backwards technologically. They typically would not understand the benefit of partnering up with a third party to execute a digital channel proposition.

And even if they did, executing the asset-liability strategy on a partnership like that is really, really hard, because the bank would need to give you something that’s at the core of his license. It’s the government guarantee on the deposits. And this is something that the banks are really, really scared to outsource to a third party. If they let you collect the deposits that is no problem, but then they probably wouldn’t let you lend out that money to consumers, because they’ll say, “I’m on the hook with a regulator for the deposits, for the safety of those deposits. So I need to really control the credit.” And they wouldn’t be incorrect in stating that, so essentially to execute that business model, you really need to have your own bank license.”

Apart from fintech players uncovering the Filipino preference for (fully) digital propositions, the pandemic and resulting lockdowns in the country (one of the longest globally) also bought time for Filipinos to spend more time online and consume digital content. This digital consumption has already been a trend even pre-pandemic, with a significant portion of Facebook users coming from the country, but while the demand had already been steadily rising, supply went through a pivotal change over the pandemic with more creator platforms and avenues to monetize content creation, from podcasts to live streaming.

While fintechs and creator economy platforms have led the way in unlocking the massive potential of the Philippines’ total addressable market (TAM), an important and often overlooked segment of this TAM came into the spotlight this year: the Filipino diaspora.

Overseas Filipino Workers (OFWs), though officially named such in the 70s, have been around since the 1920s with the sugarcane farmers, and successive generations of Filipinos heading to various countries across the globe who either bring their families along or at least send back money home have thus created global populations and communities with ties to the Philippines. Even if not all OFWs and their families stay Filipino citizens, OFWs have historically made up a large part of the country’s economic growth and are indelible to the country’s social fabric. Even local TV networks have set up separate, online channels specifically for the OFW community.

If the Philippines itself and its more than 7000 islands are not big enough, then there’s the Filipino diaspora to tap into, almost as a separate market on its own, with some startups specifically targeting the pain points of these communities. And the ability for startups to tap into this market has increased significantly with the tools to build remote-first companies and distribution.

On the podcast, Mark talks about the value of this remote-first thinking for Filipino founders. “If the Philippines isn’t big enough, you don’t need to just stay in the Philippines. There’s OFWs all over the world; you can sell to them. You see great companies like 1Export trying to do that, really trying to take advantage, with some of their products in the US. I think the great founders here are guys that [know the answer to] — “If the market that you’re targeting here has only a serviceable obtainable market of 50 million. What do you do?” — You need to kind of have that view towards a more global approach. “It’s not big enough for me [to be] in one market. I think three. I think five. How do I enter the market easily that way?”

I think one of the great things that COVID has done is that everything has been [made] remote. People are building remote organizations. People are building startups having never not been to the country they’re in. This is quite enlightening. The fact I’m talking to you and I have not met you in person as well. And people have not met their team members in person because it has been so restrictive. Naturally we lose a very big part of human interaction from that. We lose a very big part of being able to directly connect you people emotionally as well. But at the same time you gain a lot of efficiency gains.”

All in all, the Philippines’ TAM does not have to be limited to its digital or internet population, or even actual geographic population. There’s a massive opportunity to unlock the digitally underserved (depending on the service) as tonik did, and also an opportunity to unlock markets outside of the Philippines itself with strong (family) ties to the country. The ability to tap into this will depend largely on the company’s business model and go-to-market strategy.

Key Takeaways for Founders and Investors

- The TAM of the Philippines is not limited to its digital or internet population, or even actual geographic population.

- The right business model and go-to-market strategy can unlock underserved markets and even the Filipino diaspora.

- There’s also the option of going beyond Filipino markets to other countries as well, but again that goes back to the accumulated resources and insights from the primary market and ability of the founders to localize into a new market.

A Talent Boom To Flip An Age-Old Slump

The Philippines is not short of talent. It is the home of 110 million Filipinos with a 25.7 median age and the second most fluent English speakers in Asia. The urban population is raised in a highly globalized culture, thanks to generations of them being raised on the NBA, Facebook, international beauty pageants, and fairly recently, Kdramas. This combination of demographics and culture makes for among the most competitive and dynamic workforces in the region. The problem is in convincing them to be entrepreneurs in the Philippines.

For one, the business process outsourcing industry has been winning the talent attraction game in the country for the longest time. It employs 1.3 million people in over 1,000 firms that pay 3-4x the minimum wage on average across tech-enabled jobs including data analytics and customer support.

The gig economy has also shown a strong hand in the talent market. Even before the pandemic, the country has already moved up to be the sixth fastest-growing market globally for the gig industry. This is further exacerbated as the pandemic ensued, as over four million were displaced in traditional jobs as of 2020.

Of course, the corporate path has always provided relative stability, especially when it comes to local conglomerates. Over the past few decades, competition has been amplified by global tech giants and MNCs looking to establish Philippine operations.

But perhaps the biggest alternative for Filipino professionals historically is to seek greener pastures abroad. The country has reportedly lost an estimated 10% of its population to better pay, working conditions, health benefits, career progression, and general wellness in more developed countries in a massive historic brain drain. Among ASEAN peers, the Philippines has ranked #1 and #2 for exporting its nurses and doctors, respectively.

These together have historically usurped the entrepreneurial spirit and killed innovation in the country. The risk of the path of startups proved too high a cost for the average Filipino professional. For the longest time, skilled foreign entrepreneurs and half-Filipinos dominated the Philippine startup scene, as they were arguably the only ones with the risk appetite, connections, capital, and global perspective needed to survive with tech-first businesses.

Yet seemingly overnight, a new generation of Filipino entrepreneurs led by foreign-educated Filipinos launched their own startups smack in the middle of a global pandemic. And the number of startups founded and raising capital have been accelerating. The country’s 5-year tally of startup fundraising activity hit the $1.7 billion mark, only $1 billion of which is attributable year to date alone, as reported by Gobi Core Fund’s Startup Ecosystem Report. What has been causing the shift?

First, COVID-19 itself. The pandemic pushed not just the need for digital and contactless solutions as mirrored by startup trends across the world, but also the pressure on the national government to lay out policies and roadmaps for national digitization. The year 2020 saw the launch of BSP’s Digital Payments Transformation Roadmap, the DOST’s Startup Grant Fund Program, and various other government initiatives to provide financial grants and non-financial benefits to support R&D, training, regulation, and venture funding. Just in the Philippine Startup Week 2021, the National Development Co. announced its Philippine Startup Venture Fund, committing $10 million to startup investments between 2021 and 2022.

Second, the cross-pollination of talent and ideas in the local startup community. Formal networks connecting ecosystem players have existed for years. An example is the Manila Angel Investors Network (MAIN), which was formed in 2016 by a group of angel investors aiming to help each other source, analyze, and invest in local startups. What accelerated this is an active initiative to co-locate Silicon Valley style in the local tech scene named Sinigang Valley — reminiscent of its US counterpart and tweaked just enough to represent the hotpot yet distinctly Filipino culture in the space.

The quality of founder talent has also increased as returning migrants who were previously part of the brain drain brought top skills, experience, connections, capital, and ideas to help create highly localized startup solutions for universal problems.

Third, emerging success stories. Among these is the first big exit seen in the country through Go-Jek’s acquisition of Coins.ph for $72 million in 2019. Besides this, fundraising has been relatively more accessible with the entry of independent country-focused funds and regional investors alike, many of whom made their first Philippine investments between 2020-2021.

The Philippines also seems to model the emergence of homegrown talent in Indonesia. In our podcast, we asked Rick Firnando, Co-Founder and CEO of Verihubs, what the biggest misconception is about the Indonesian tech space. He says, “Most people will say in terms of education, [Indonesia] is not as good as studying abroad, But Indonesia education is improving and there are a lot of founders from Indonesian universities, not to mention Hendra and myself. We’re actually improving from the education [standpoint].”

We see a similar emergence of success stories among locally-educated and homegrown Filipino founders. A prime example is ER Rollan of GrowSari, the country’s biggest B2B platform for neighborhood mom-and-pop stores called sari-sari stores that are similar to warungs in Indonesia. Educated at the University of the Philippines and with about a decade of experience in FMCGs and consulting in the consumer industry, he had a unique understanding of the significance and complexities behind sari-sari stores juxtaposed with an expertise in regional best practices in the consumer space. GrowSari has since grown, currently ranking second among the top revenue-generating startups in the Philippines in 2021 as reported by the Esquire Philippines Research Team.

The clear government direction, strong ecosystem support, and abundance of venture funding and emerging success stories together make a strong case for the return of Filipino talent specifically to the tech scene within the country. As Oliver Segovia in Harvard Business Review put it, “[For the Philippines], [working] for a venture-backed startup is the new status symbol.”

Key Takeaways for Founders and Investors

- While the BPO industry, the gig economy, the corporate path, and the lure abroad have historically claimed top Filipino talent, there is a massive reverse brain drain sparked by the pandemic, community growth, and founder success stories.

- The perceived risk behind the startup founder path in the country reverses as more support is injected in the way of government roadmaps, startup hubs like Sinigang Valley, and the availability of local and foreign venture capital since the pandemic.

- Homegrown talent is emerging with locally-educated founders at the forefront.

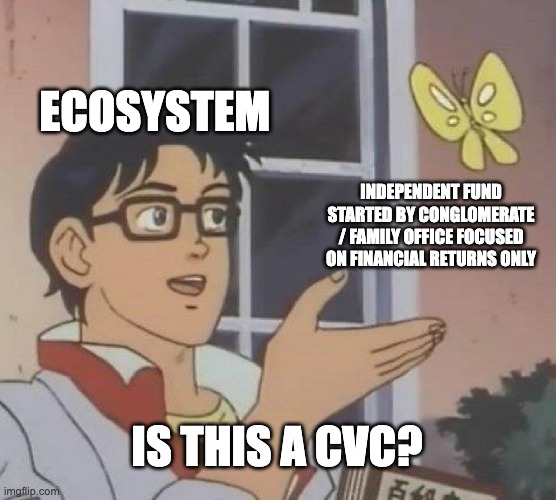

Diversification of conglomerate capital means more room for foreign capital and homegrown VCs

Startup funding in the Philippines has historically been driven by the conglomerates, many of which emerged in the latter half of the 20th century as many industries in the country were privatized and government utilities were sold to families, essentially creating duopolies or oligopolies.

The conglomerate approach has generally been to come in early and buy a significant portion of the company or build up a competitor that then outspends or acquires the independent competition, but that has steadily changed over the past decade, with more family offices and conglomerates setting up CVCs or independent funds that are less strict and more opportunistic about strategic investments like Kickstart Ventures (not limited to strategic investments) or the Gentree Fund (purely financial mandate with opportunity for SM value-add). Some of the 2nd generation or 3rd generation members of the families that own these conglomerates have also begun more actively angel investing. In an earlier article this year, we wrote about family offices investing in earlier and earlier stages, and even investing directly into startups, and we also see a similar trend evolving in the Philippines.

Mark talks about the funding landscape in the Philippines on the podcast and how it has been developing. “So not many people in Singapore know that much about the Philippines in the sense of actually having been to the market quite a bit. I think anyone who has been to the Philippines even once, you know how big the SM group is. The moment you land you know, so when I heard that there’s a chance with the family office of the SM group to launch this venture strategy. I was like, “Oh, wow. I mean you can’t really say no to that.” I mean, this is such a big group. They were at that point starting to really think digitally in a bit of a bigger way. This was pre-COVID that I was starting to talk to them. I think this was February or March when you started hearing China was starting to lock down a little bit, [and] people were getting a little bit worried, but no one thought that it would last as long as [it has]. I think everyone thought it would be like SARS. I think that’s what the assumption was.

I think that was when people started to really think about digitalization and at that point Philippines venture [capital]-wise, Foxmont was already there. Foxmont has been there for some time. I love the guys there. Franco’s really great there. [And] you had the CVCs, you had the Kickstart guys, the JGDev guys. So I knew that the SM side of things will kind of look into doing something in the venture space as well. It kind of makes sense. This is a natural extension of the strategy as well, but I guess it’s [also] how we have really shaped that sort of strategy, right? Does a CVC approach work better or does a financial VC under the family office work better? And I guess it also goes into the family’s plans as well for the fund itself.

So the way we structured it, and I guess why I was brought in try and replicate a very similar sort of — I wouldn’t say completely, but they are very different markets. [They have] very different linked affiliates in that sense. Gojek is quite a different sort of animal in a very digital format. That’s why I was brought in, to launch this new strategy, which kind of mirrors it because we wanted to have a financial mandate that allows us to make financial returns. And that’s the key goal for Gentree right. It’s to really work with the founders to maximize portfolio value. So we are always sitting on the side of the founders. We want to really maximize portfolio value here. We don’t want to control any startup because that’s not the way to allow a founder to really grow. We never ever go above 20% of any cap table, but tend to stay within the 5% to 10% range typically. In terms of the fund itself, the way we provide value is through very arm’s length support from SM. So we wouldn’t be offering any preferential terms because that is typically limited to affiliates of SM itself.”

With the many options for conglomerates to invest in startups (strategic investments, set up venture builders, set up CVCs, or set up independent funds), the choice of approach really boils down to the leadership’s outlook on the country’s startup ecosystem and how it relates to the conglomerates’ focus industries.

The importance of this diversification in conglomerate approaches to investing in startups means that regional and global investors no longer have to confine themselves to entering in later stages or be worried as much about getting boxed out of deals. This has led to more regional VCs setting up local investment teams in the country, and even local early-stage funds being able to gain more traction in terms of generating follow-on dollars for their portfolio, serving as platforms to connect Filipino startups to the larger VC community.

Another trend tangent to this influx of more foreign capital into the country, and also tied to the Filipino diaspora we talked about earlier is the increasing number of angel investors from abroad with roots in the Philippines and looking to invest in startups in the country, if not return to the country. This only adds to the diversification in early-stage funding that will be critical to get startups from seed to Series A and “sell” them to regional or global investors for later stage funding.

Key Takeaways for Founders and Investors

- Funding sources are diversifying in the Philippines, even amongst the approaches conglomerates are taking to invest in startups, where there are not just strategic but also financial incentives.

- This diversification creates more room for regional and global investors on cap tables even early on in the growth of the startup.

- Homegrown early-stage funds are a valuable platform to connect local startups with regional or global investors.

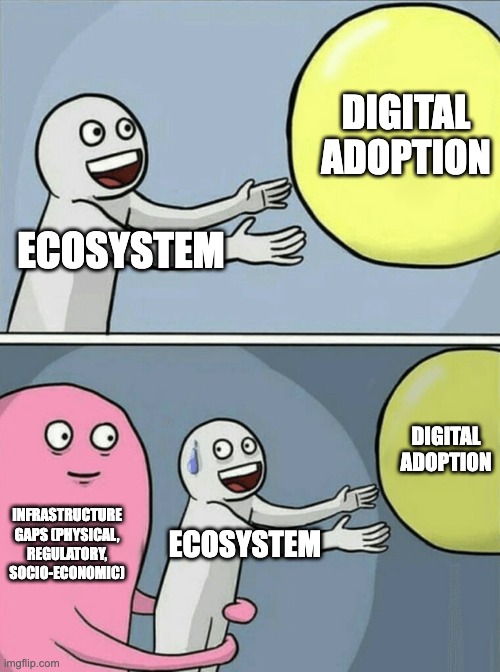

Governments can’t buy unicorns; they need to build them stables

According to Nitin Pangarkar, an associate professor at National University of Singapore, developing economies will develop startups more effectively if they pay more attention to creating positive regulation, increased digitization, and a conducive overall business environment rather than providing grants and incentives themselves.

The Philippines is slowly aligning with this. The Innovative Startup Act, Philippine Innovation Act, Ease of Doing Business, CREATE Law, and One Person Corporation all encourage entrepreneurship and the growth of startups in the country. Some notable developments include the startup visa for those looking to set up shop in the Philippines and the establishment of talent development programs like the Regional Startup Enablers for Ecosystem Development (ReSEED) Program, Women-Helping-Women, and the Higher Education Institution Readiness for Innovation and Technopreneurship (HEIRIT) Program.

Another crucial factor is the ease of access to digital services. Just like its SEA neighbors, the Philippines is mobile-first, with the average cost of connectivity being driven lower and lower as telco services in the country become more and more competitive. This is combined with the DICT recently rolling out its National Broadband Program and Free Wi-Fi for All Program. These set the scene for pure-digital plays like tonik’s banking services, Kumu’s mobile content and community platform, the gaming boom as captured by Yield Guild Games, and other emerging contenders.

Key Takeaways for Founders and Investors

- Infrastructure gaps relating to digital, political, and socio-economic factors must be given government priority to fully develop the Philippine startup scene.

- The Philippine government moves towards a regulation-first approach to supporting startups, supplanted by non-financial benefits and training programs to boost talent.

- Since mobile and internet access in the Philippines has been improving, it particularly boosted pure-digital plays and gaming solutions in the country.

The Bayanihan Spirit: Unicorn Creation is not in a Vacuum

It takes a village — and in the Philippines, that’s called the “Bayanihan spirit”. With full support from the government, local conglomerates, folks from Sinigang Valley, other startup community hubs, and the ever-hungry Filipino diaspora, combined with inspiring successes of local startups and the country’s digital transformation, the Philippine startup ecosystem seems to be at an inflection point.

Persistent challenges — infrastructure issues, regulatory holdbacks, tech talent, availability of funding — seem to fade against a developing Filipino startup narrative: that the Philippines may soon see its first generation of unicorns that are set to kickstart a flywheel of innovation in the country.

If you’re an unstoppable startup founder building in crypto and web 3.0 in Southeast Asia, or in any sector in the Philippines, we’d love to meet you! Reach me at chelsey@insignia.vc or Chelsey Pua on Linkedin.

Chelsey is an investment analyst at Insignia Ventures. Prior she was an analyst at Fortman Cline Capital Markets and Foxmont Capital Partners. She specializes in blockchain and crypto as well as Philippine startups.