This article contains excerpts based on the webinar held on 30 August 2020 on Supercharging Remote Productivity, in partnership with Huawei.

With the rise of the internet company, remote work emerged as an inevitable development in the way we work — the next milestone after the Industrial Revolution ushering the factory and office. The tools are there, with videoconferencing, chat apps, and data storage platforms. The incentives are also aligned between jobseekers and companies.

Remote work has evolved as a way for companies to tap into a larger pool of talent, especially in markets where the cost is lower. It has also become a way for jobseekers, mostly millennials and Gen Z, to access career opportunities and experiences that they would not have been able to have in their locality, without having to take on the costs of adjusting to a new country. This has led to the rise of outsourcing, most often business support or customer service and software engineering and development roles.

While remote work has been around for a few decades, it’s only during this COVID19 crisis that companies have been forced to place remote work front-and-center. And not just any kind of remote work, but work-from-home (WFH).

But WFH has proven to be easier said than done. While tech giants like Facebook and Twitter are able to leverage their own internal tools and organizational structure to transition teams to WFH, tech startups and SMEs are not as equipped or not as mature. Remote operations require a certain level of institutionalization (ie set processes) and task delineation across roles.

That said, it’s not impossible. Even as countries reopen after months of lockdown, there’s certainly the impetus to develop teams that are prepared to go remote, if not stay remote for the long-term. We talked to three technology leaders with experience managing remote teams across Asia: Jianfeng Lu, chairman and co-founder of conversational AI talkbot company WIZ.AI, Kelvin Chng, co-founder and Head of Tech at Southeast Asia’s leading car marketplace Carro, and Ridy Lie, Insignia Ventures Partner and Head of Tech.

From their experience managing remote engineering teams even before COVID19, they share insights on how to build an effective remote-ready (if not remote-first) culture, which we curated into five key points:

-

Small teams, but never alone.

-

Find good tools that remove FOMO.

-

Set up “anchor” meetings.

-

Small steps, fast pace.

-

Set checks for the “quality” of productivity.

While their experiences have largely revolved around managing software engineers, their learnings apply to remote operations in general. And even though WFH will likely not be gospel by the time this crisis has passed and we will readily return to our offices, certain teams and companies will find remote a better arrangement. Others will upgrade their business continuity programs to go fully remote if ever the need arises again.

(1) Small teams, but never alone.

Kelvin Chng, co-founder of Carro

Carro’s engineering team is spread out across Singapore, Vietnam, Indonesia, Myanmar, and a pair based out of Wuhan. For Carro’s engineering team, forming small teams across multiple markets was not intended, but a result of tight corners in the local hiring market. “Hiring engineers is extremely difficult in [Southeast Asia],” says co-founder Kelvin Chng, “so we chose to go where talents are, rather than being fixated on a [specific] country.”

But even with the inevitable fragmentation, they made the conscious decision that every country they would go into to expand their engineering team they would never hire only one. “When we [brought in] our first foreign overseas hire, that person was alone in the country without any support structure — no colleagues, no office, nobody to pow-wow with, nobody to brainstorm or bounce ideas with.”

Concerned about the wellbeing and long-term commitment of their first remote hire, Carro wanted to make sure that their remote hires feel involved and part of the team, in spite of being physically miles away from the office. This commitment means that they can’t just hire carelessly in any market — Carro needs to be prepared to build a remote team in the market if they do start hiring for remote positions there.

“We make sure that we have a team. We make sure there’s a support structure around that person so that there is a certain level of teamwork that they can actually experience [in] that structure itself,” says Kelvin.

That support structure goes beyond building a team. They also ensured that their remote hires are roped into major conversations, even if they are not involved in the immediate work at hand. Ensuring awareness and involvement is important in creating that sense of belonging. As Kelvin put it, “We do not work like an offshore center — “Oh, okay. This team does this, that team does that” — we don’t do that. Ours is a team structure.”

And these conversations aren’t confined to work. “We use Slack for communication for the most mundane stuff. So we even created a channel to post, “What did you guys have for lunch? Or what did you guys do over the weekend?”…We have Telegram channels, we have WhatsApp channels, [where] they do share about what they’re eating and stuff.” By creating online spaces for remote teams to interact beyond work-related conversations, Carro’s remote team is able to transcend the distance and come as close as possible to the kind of camaraderie that comes out of face-to-face interaction.

So while forming fragmented, small teams are part-and-parcel of expanding into remote operations, they are ways to work around the separation and innovate the kind of interactions employees are able to have.

“In a nutshell, the key here is to make sure that even without the physical office, face-to-face interaction, that bond that you build cannot be in any way lesser than what it’s supposed to be,” says Kelvin.

It is really a culture-building effort. As Insignia Ventures’ partner and head of tech Ridy Lie puts it, “We have a small team, but we’ve always adopted the remote-first culture. So that means as a company, we are committed to make it this first-class experience for remote workers. If you are working in different countries, if you’re working at your house or in the coffee house, we give you a commitment that you will not be missing anything. All our processes and tools are designed in such a way that more than workers will be able to fully participate.” This approach to building remote teams fosters inclusivity while still being able to hire and manage talent from anywhere in the world.

(2) Find good tools that remove FOMO out of the equation.

From the get-go, finding the right collaboration and communication tools are necessary for creating tight-knit remote teams. “If we were to operate these small teams, we needed better tooling, better collaboration. So right from the start, we tried to find tools that will allow multiple small teams to communicate with each other,” says Kelvin.

Lark Workplace feature offering integration with other applications

As COVID19 rendered office work unsafe, WIZ.AI began using Larksuite, Bytedance’s work collaboration platform. According to chairman and co-founder Jianfeng Lu, “It’s a combination of tools, several different features, such as messaging like Slack, collaboration docs like Google Docs, shared drive, like Google Drive, video conferencing like Zoom, and also a team calendar, translation tools, integration, et cetera.” For Jianfeng, this ubiquity in capability has made it a very practical platform for his team transitioning in and out of remote work as lockdowns and reopenings varied across markets.

Kelvin also tried Larksuite before COVID19, but his team was already settled with Notion. “So Notion is our defacto tool in communicating. We have online [sharing] of documents, and we’re able to share files in there. We don’t have the video conferencing capabilities, but it actually promotes a lot of discussions and a lot of accountability in how a discussion goes, because the changes and comments are recorded.”

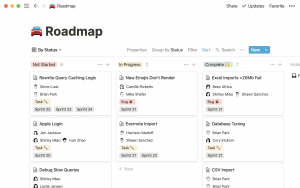

Notion

According to Kelvin, this ability of Notion’s platform to provide “accountability” accommodates the different experiences of engineers with different seniority. Senior engineers are able to develop the document further as a record for the more junior members of the team to review and read up on.

Regardless of the tool of choice, it should be able to remove the “fear-of-missing-out” (FOMO) effect out of the equation. The best remote teams are able to operate and interact in a way that isn’t in any way significantly less productive than being in a physical office. Thanks to COVID19, more and more tools designed to do this are coming into the fold, or in some cases, companies in the productivity space like Microsoft are adjusting their platforms and offerings to remote-first operations.

(3) Set up “anchor” meetings to work with personalized schedules.

Remote operations don’t just mean fragmentation in space, but also in time. Even within close enough time zones, schedules can easily go out the window. For every employee adjusting to work from home, there’s serious mental work and discipline that goes into delineating working from non-working hours and aligning that segregation with one’s own personal working style. Distractions abound, though in most cases, employees have to take care of other responsibilities especially if they are working from home, from spending time with their children to cooking their own lunch.

Kelvin shares what he’s observed from his own team. “I do have staff who start working or being productive after 7:00 PM. And I have staff who will take longer lunches because they are at home where they cook. So they prepare longer lunches. And at the end of the day, they don’t stop work at six, they stop work at [around] nine. So it really depends on each individual way of wanting to operate within their own confines and their own structure.”

In an office work setting, managers and employees would normally leave at the same time once work for the day has been completed. But with remote work incentivizing personalized work schedules, accountability is more difficult to monitor from the manager’s point-of-view.

But it would also not be productive and practical to force a standard schedule for remote employees. From the employee’s point-of-view, once they’ve gotten into a certain rhythm that works for them, disruptions and distractions can be difficult to handle.

Jianfeng Lu, chairman and co-founder of WIZ.AI

For Jianfeng, adjusting to distractions is a problem he can easily relate to. “When I was looking for my first job, I wanted a job [with] high salary, responsibility, and work from home. And always [working] from home makes me happy. I can save commute time to sleep and enjoy my expensive and very good speakers and drink my favorite tea…But the problem is like always a lot of distraction and always I need to spend a lot of energy and the discipline to [get] back to work.”

Distractions and disruptions are costly for productivity. “Once an engineer gets distracted, it actually takes a lot of effort and willpower to start again. Most studies actually say that the average time for an engineer to get back to work, once they get disrupted, even for a few minutes, it’s around 15 to 20 minutes. So if an engineer gets distracted four times, five times in a day, that’s an hour or more than an hour of time down the drain,” says Ridy.

So instead of enforcing standard schedules or bugging employees for updates, the most effective solution would be to set up quick update meetings that “anchor” the team together. Pick a short window of time that works for everyone, and allot that time solely to getting updates from everyone.

At WIZ.AI, Jianfeng introduced 10 to 15 minute daily huddles in the morning. During these huddles, everyone shares with everyone else what they have accomplished, and what they are going to do and achieve for the day until the next huddle. This practice has proven to be especially useful for certain projects requiring handovers as they progress.

The key here is being able to create time for collaboration and communication even with the varied work styles and personalized schedules that come out of employees working from different environments.

(4) Small steps, fast pace to keep focus and prevent overload.

Companies that transition smoothly into remote operations are able to translate company growth into specific, rapidly achievable goals for employees. As Jianfeng put it, “Small steps, fast pace.”

The WIZ.AI team works on one major release for their system every three weeks, and between those releases, one or two minor releases every week. And with each release, they identify improvements that customers can clearly perceive and engage with. With this product development cycle, Jianfeng says “everybody can easily sense the progress and delays.” This focus enables them to develop their product rapidly even if they are working remotely.

And it’s also important for feedback and preventing overload. Adopting “small steps, fast pace” into a team’s feedback cycle sets a manageable rhythm for employees while still retaining alignment towards larger company goals.

“You try to give them a shorter or clearer goal that they can finish in one week or so, like playing a game where you have very quick feedback [mechanisms],” says Jianfeng.

Addressing the potential for overworking is especially important for remote engineering teams, according to Ridy. “Very passionate and hardworking engineers can sometimes overload themselves, and they’re working too hard. In Insignia, what we want is for [our] people to have long-term success, which means you’re not burning out. You are taking care of yourself outside of your career, you’re also taking care of your family.”

“So in a little way, our approach is pretty sensible, where we emphasize to our employees that their wellbeing is important us. We don’t value them only as a contributor by how much they are able to code. We value a long-term partnership with them. We want to grow. We want them to continue contributing to our companies. And in the process, everyone will be in a better place,” says Ridy.

Once again, managing remote teams has proven not only to be a matter of implementing processes or introducing tools but also fostering a culture of empathy and communication.

(5) Set checks for the “quality” of productivity.

Remote work doesn’t change the end product of the business as much as it does the process so most adjustments deal with schedules or communication. But given the process has to adjust significantly, there must also be more attention paid to the quality of the end product. “We don’t actually have any difference in the way actually measure productivity pre and post-COVID. But the other part of productivity is not the output, but also the quality of the code that is being developed,” says Kelvin.

In an office setup, managers and leaders can easily course-correct and monitor how the pace of work (ie productivity) relates to the end product. But in a remote work operation, there’s a disjoint between process and end product, and even the best collaboration tools don’t make the business impervious to blind spots.

There’s also the incentive that working from home places on finishing work as fast as possible, leaving output prone to error. Kelvin says, “The bonus of working from home is you want to try to clear your work as soon as possible so that you have more free time for yourself…That’s why we are certainly more concerned about the quality of the output as compared to the number of output that we actually get nowadays.”

Ridy Lie, partner and head of tech at Insignia Ventures Partners

This can easily lead to micro-managing, but that also isn’t the best answer, both in and out of the office. “Having your boss somewhere in the office doesn’t change your productivity. In fact, again, I read some surveys that say having a feeling that you are being watched will actually make you less productive,” says Ridy. “You just feel that you were being watched. You feel that you’re not a hundred per cent solving the problems. And engineering is a creative problem. It’s a problem that requires a lot of brainpower. So, if get this lurking feeling that somebody is watching you, that’s not gonna help you much.”

Instead, when it comes to output like code, various “QA” checks can be set in place.

Kelvin says, “As engineers, we all know there are many ways to skin the cat, right? So we are also increasingly conscious about that and trying to make sure that we have a more robust review or peer review across the entire code base, make sure that things are kept up to a certain standard before they are released into our production.”

***

For businesses, WFH plays into the larger trend of digitalization, where it’s not just the workforce but entire operations moving online. While remote-first is being adopted by big tech names, it is likely not going to be the rule of thumb for tech companies. Instead, this WFH “experiment” many companies have been forced to undergo will open doors for companies to be more flexible with work arrangements. As Kelvin put it, “It wouldn’t be whether it’s remote or not, but where the person is most comfortable working.” Ultimately, people want to enjoy their work, whether that means working from home or from the office.

If you’re a software engineer looking for great tech companies to work with remotely, check out open positions with our portfolio companies at career.insignia.vc.

Paulo Joquiño is a writer and content producer for tech companies, and co-author of the book Navigating ASEANnovation. He is currently Editor of Insignia Business Review, the official publication of Insignia Ventures Partners, and senior content strategist for the venture capital firm, where he started right after graduation. As a university student, he took up multiple work opportunities in content and marketing for startups in Asia. These included interning as an associate at G3 Partners, a Seoul-based marketing agency for tech startups, running tech community engagements at coworking space and business community, ASPACE Philippines, and interning at workspace marketplace FlySpaces. He graduated with a BS Management Engineering at Ateneo de Manila University in 2019.